Digital concerns underpin many of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Gender equality, good health, quality education, industry innovation, smart and sustainable cities: these all require strong information and communications technology systems to become a reality.

For all of this to happen, developing countries will have to overcome the “digital divide”. This refers to the gap between those who are connected — first to voice and now to Internet services — and those who aren’t.

But there’s a problem. We simply don’t have the data in developing countries, and in global statistics, to know what the status quo is or whether the digital divide is being closed. So we don’t know if information and communications technologies are contributing to the achievement of the SDG targets.

There is some supply-side data provided by operators and collected by regulators. This is fed into the UN statistical system. It’s then used as the basis of multiple digital indices that now exist. But this has many limitations for policy or planning in developing and emerging economies.

For example, it can’t be used to measure several basic indicators — like gender, age and income levels — in the predominantly prepaid mobile markets of the Global South.

The After Access Survey, which was run across 16 countries in the Global South in 2017, fills some of these data gaps. The survey tells us who has access to and uses mobile phones for what purposes. It also reveals data about Internet users and non-users, and the reasons people aren’t online — usually, because Internet enabled devices are too expensive.

Digital indicators

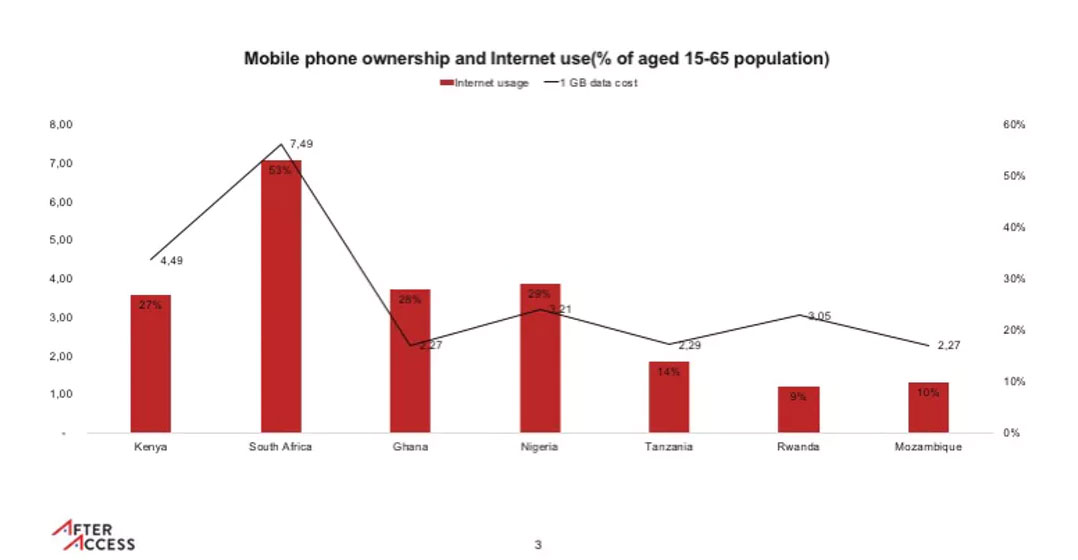

All this allows us to compare digital indicators from a range of countries and to see patterns among countries. It shows us that in large populations like Nigeria, India and Bangladesh, irrespective of their distribution of wealth its a struggle to get people connected.

It enables better comparisons on outcomes between countries with similar size economies. We can also compare ICT policy outcomes in the countries that were surveyed.

The findings offer a useful guide for policymakers. This is because the survey is nationally representative. It unmasks the inequalities in the national aggregations. This allows policymakers to see beyond the descriptive statistics to identifying the determinants — like education and income — of Internet access and use.

These perspectives underscore the fact that addressing digital inequality isn’t a technology problem. It’s a classical development challenge.

Key findings

As the world moves from simple voice services and devices to more complex Internet-based services, the issues of digital inequality become more complex than just connectivity. More comprehensive indicators and data modelling is required to understand issues of inclusion and exclusion, and what factors are driving them.

The After Access survey provides the only representative insights into who is on the Web, what they do, who is not and what prevents them from getting online. These were some of the key findings:

- In the seven African countries surveyed, individuals have an average of two Sim cards (which are captured in the supply side data as two subscribers). There are two likely reasons for this. The first is that it allows people to get a signal when there is not one for their primary provider. Secondly, they have another Sim to make cheaper calls to speak to people on other networks, or if it’s a data card, to get a promotional package, such as a “free” social networking time with a new card.

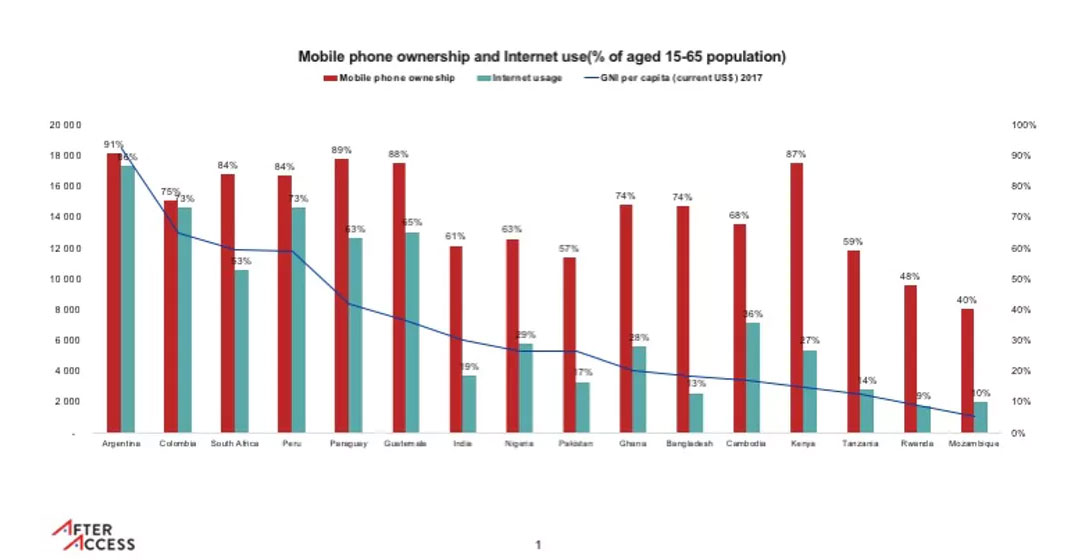

- Mobile phone penetration and Internet penetration across the globe is broadly aligned with gross national income per capita. Broadly speaking, countries with richer people on average are more connected than poorer countries.

But our findings also suggest interesting variations.

Overall, the five Latin American countries surveyed, together with South Africa, have the highest mobile phone penetration rates. But South Africa has a lower Internet penetration rate than any of the Latin America countries. This includes those with lower gross national incomes.

Overall, the five Latin American countries surveyed, together with South Africa, have the highest mobile phone penetration rates. But South Africa has a lower Internet penetration rate than any of the Latin America countries. This includes those with lower gross national incomes.

Myanmar and Cambodia have much higher Internet penetration rates than African and Asian countries with similar gross national income rates. They also have higher rates than their larger gross national income counterparts, India and Nigeria.

Myanmar and Cambodia have much higher Internet penetration rates than African and Asian countries with similar gross national income rates. They also have higher rates than their larger gross national income counterparts, India and Nigeria.

Genuine redress

These indicators, and other data collected in the After Access survey, can be used to provide evidence that can help policymakers and planners and assess the impact of policy outcomes.

They can confirm — or challenge — general assumptions about relations such as gender; or about the relationship between economic growth and Internet penetration. They can also clarify thinking about what the biggest challenges are to getting people online.

The affordability and human development challenge is far more difficult to solve than the infrastructure deficit with which development banks and governments’ are preoccupied. In many countries, networks cover between 60% and 80% of the population. Yet there is less than the 20% Internet-connected critical mass required to see the network effects associated with economic growth and development.

And even where enabling environments that are conducive to investment have been created for the extension of networks, our survey data illustrates how the socially and economically marginalised are unable to harness the Internet to enhance their social and economic well-being.

The data available shows that besides affordability, human development — particularly education and the resulting income — are the primary determinants of access, intensity of use and the use of the Internet for production; not only consumption.

Policymakers need to extend their lenses to the development of relevant local content and applications in local languages. These are all important stimulants to getting people online if countries hope the harness the benefits of the Internet for all their citizens.![]()

- Alison Gillwald is adjunct orofessor, Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, University of Cape Town

- This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence