South Africa will soon agree on a comprehensive, unified approach to turning around Eskom, which is saddled with R402-billion in debt, according to the minister who oversees the state power utility.

Eskom, which depends on coal for the bulk of its electricity generation, has subjected the country to intermittent rolling blackouts for more than a decade and accounts for about 40% of its climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions. Wide-ranging and at times conflicting suggestions for fixing the company have been flighted by national treasury, the energy department and the utility itself.

Options on the table include selling some of its old coal plants and accelerating the retirement of others, capturing carbon emissions, getting the state to take over half of its debt and converting R82-billion of bonds held by the Public Investment Corporation into equity.

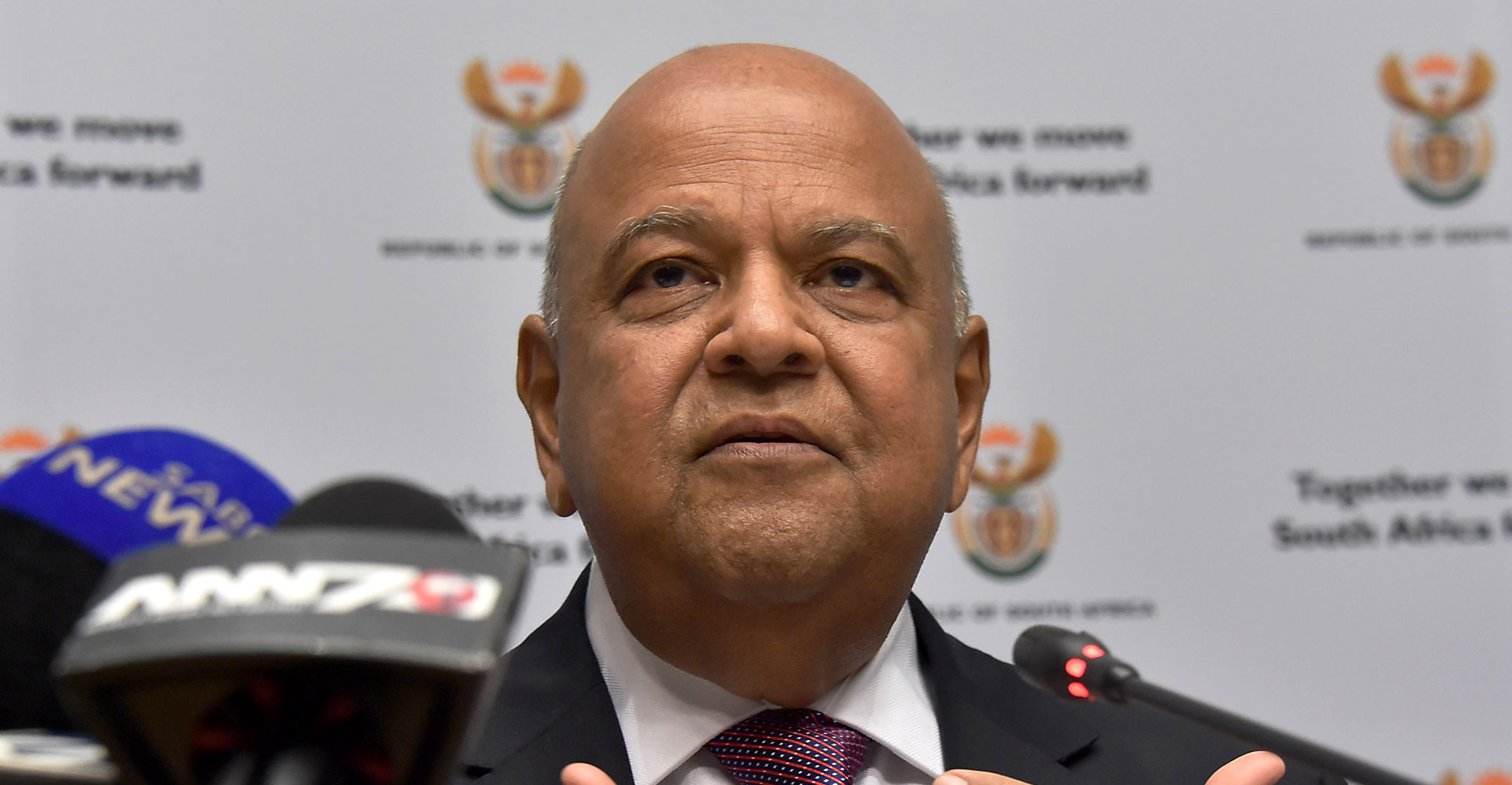

“There is absolutely going to be one voice as we go forward into 2022 and one direction that we want to go in as well,” public enterprises minister Pravin Gordhan said in an interview. Eskom “will look a lot different than it does today” by the end of the current administration’s term in 2024, he said.

President Cyril Ramaphosa pledged to address operational problems at Eskom when he took office three years ago and root out the corruption that dogged the company during his predecessor Jacob Zuma’s rule. But power outages have increased to a record this year, curbing output and economic growth, while the utility has posted four consecutive annual losses and is still contending with theft and mismanagement.

Years of so-called state capture have left a lasting mark on the company and it will take time to address the damage and change its culture, according to Gordhan.

“In some cases you would want to fire somebody on the spot, but legislation won’t allow you to do that,” he said. “It would be nice to be able to do that — if you are caught red-handed you get fired right now, pack your bags, go home and find another job somewhere else.”

Progress has been made on splitting Eskom into generation, transmission and distribution units — a process that Gordhan said will be completed next year.

“That will give us a much better idea of valuations of each of the three entities and then we will have to work out how we attribute debt to each of those different entities and resolve the remaining amount,” he said. Finance minister Enoch Godongwana will have to decide whether the government assumes part of Eskom’s debt by the time of the budget in February next year, giving consideration to the serious fiscal constraints the country is facing, he said.

Godongwana has voiced opposition to the utility taking on more debt until its balance sheet has been repaired, potentially by selling coal-fired plants. The idea is a relatively new one and is being explored, according to Gordhan.

Profits by 2026

“We might want to dangle an idea out there in the public domain” to gauge the reaction, he said. “Some of you might say: ‘Who would be stupid enough to buy a power station?’” but there are those who will consider it, he said.

Eskom has said it expects to return to profit in 2026 and has outlined plans to add a renewable energy division that will invest as much as R106-billion in wind and solar projects, enabling it to reduce its carbon footprint. Western nations have offered US$8.5-billion in grants and concessional loans to help South Africa transition away from coal.

Gordhan said he backs an expansion into green energy, with the country needing to expand its generation capacity at the same time as replacing the megawatts it loses as coal plants are shut down.

The minister also voiced support for Eskom CEO André de Ruyter, who has faced calls from labor unions and some business groups to resign over the utility’s failure to end rolling blackouts.

The minister also voiced support for Eskom CEO André de Ruyter, who has faced calls from labor unions and some business groups to resign over the utility’s failure to end rolling blackouts.

“He has my 150% backing. Eskom is an entity that has gone through a difficult time and the challenges in Eskom are not easy ones, given the problems that we’ve had with corruption and what we call state capture in South Africa,” Gordhan said. “We need to take extra measures to give him the support he requires.” — Paul Burkhardt and Paul Vecchiatto, (c) 2021 Bloomberg LP