[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he 23-year-old who saved the world from a devastating cyberattack in May was asleep in his bed in the English seaside town of Ilfracombe last week after a night of partying when another online extortion campaign spread across the globe.

Around 6pm on 27 June, Marcus Hutchins, a self-taught computer security researcher and avid surfer, was awakened by a phone call from a colleague telling him another attack was underway. Dreading a return of the virulent WannaCry malware that he stopped in its tracks the previous month, Hutchins logged on to his computer in the house he shares with his parents and younger brother to scan the latest reports.

By then, more than 80 Ukrainian banks, government agencies and multinational firms including shipping giant AP Moller-Maersk and Russia’s biggest oil company Rosneft had been hit by a ransomware attack spreading like an electronic plague across their networks. Within 20 minutes, Hutchins later recounted, he got hold of a sample of the malware and was relieved to see it wasn’t another WannaCry, which infected hundreds of thousands of computers in more than 150 countries, but something more targeted and less virulent.

Though both attacks took advantage of flaws in Microsoft’s Windows operating system to spread their payloads, WannaCry used the Internet to propagate itself — each compromised computer would scan and infect another, creating a snowball effect — while the so-called Petya attack was confined to local networks. Petya appeared bigger at first because hackers hit Ukrainian software company M.E.Doc and used an automatic update feature to download its malware onto the computers of all users of the software, Hutchins said.

Unlikely hero

Researchers like Hutchins and his colleagues at Los Angeles-based threat intelligence firm Kryptos Logic are akin to seismologists, scanning the Internet for electronic tremors that could signal the next attack. This time he was only an observer, but on 12 May Hutchins stopped the WannaCry attack that crippled organisations from Britain’s National Health Service to Deutsche Bahn in Germany and Renault factories across Europe.

With a mop of curly hair, baggy jeans, T-shirt and sneakers, Hutchins is an unlikely hero. He rarely leaves rural north Devon, where he has lived since he was 8, and hadn’t travelled abroad until last year. He learned to program computers at 12 and was tracking and disrupting botnet attacks for his own enjoyment before anyone paid him to do so.

Hutchins started a blog under the pseudonym MalwareTech while still a teenager and was hired by Kryptos in 2015. He said his parents and friends didn’t even know he had a job until the WannaCry attack.

Hutchins was supposed to be enjoying a week’s holiday, but returning home after a lunch of burgers and cheesy chips with a friend and seeing the carnage WannaCry was inflicting, he couldn’t resist jumping in.

“The fact that so many NHS trusts were being hit at the same time was pretty much unprecedented,” Hutchins said in an interview a few weeks after the attack, drinking Coca-Cola in a hotel bar in Ilfracombe, a picturesque but faded tourist town. “That for me was a massive red flag, which showed that this thing was spreading on its own.”

Most ransomware, which encrypts files on a target machine to force its owner to make a payment in exchange for decryption, is spread via e-mail attachments from rogue senders that infect host computers when they’re opened. Hutchins said he’d expect a handful of people to click on a mass e-mail over a few days, not thousands of employees at scores of medical facilities at the same time.

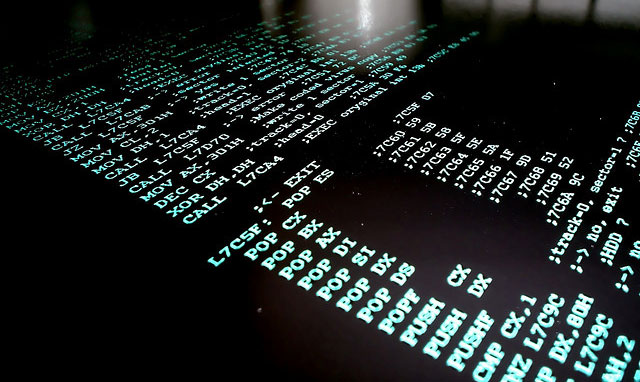

After analysing a sample of the malware and seeing it spread by exploiting vulnerabilities in Microsoft’s network file-sharing protocols, he realised it was using a cyberweapon allegedly stolen from the US National Security Agency. Known as “EternalBlue”, it was part of a cache of sophisticated NSA hacking tools targeting Microsoft software that were obtained by the Shadow Brokers criminal gang last year and leaked onto the internet in April.

Hutchins also noticed a quirk buried deep in the malware code. It tested for the existence of an unregistered nonsensical domain name. He promptly registered the domain for £8.50 (about R150) and redirected all traffic to a server designed to capture malicious data, known as a sinkhole, which would allow him to monitor the progress of the attack.

Kill switch

Although he didn’t realise it at the time, Hutchins had inadvertently triggered the malware’s kill switch. Before infecting and encrypting a computer’s hard drive, WannaCry would query the domain, and as long as it remained unregistered would proceed with the attack. Now, when the malware checked the domain and found it active, it immediately shut down. About 100m attempts to infect computers, including more than seven million in the US, have been mitigated since then, according to Kryptos data.

“At the time, we were just like ‘Yay, we can track it now’, we didn’t know that we’d stopped it,” Hutchins said. “The minute we registered the domain we were looking at like 5 000 or 6 000 unique systems all connecting, and it went up to 200 000 within an hour. I remember thinking: holy shit, this is really big.”

Hutchins is part of a global community of online security researchers and bloggers who battle with hackers and cybercriminals from their home offices at all hours of the day and night. Given the wave of attacks in recent years, they’re in high demand from governments and corporations and can command six-figure salaries while still in their early 20s.

Hutchins said he has been courted by some of the world’s biggest cybersecurity firms. In 2015, he interviewed with Britain’s top-secret Government Communications Headquarters but went to work for Kryptos instead after it made him an offer he said he “couldn’t refuse”.

“He’s a natural talent,” said Salim Neino, 33, Kryptos’s CEO, who hired Hutchins after reading his blog. “He was obviously solving hard problems and he wasn’t doing it for monetary reward, and those are some of the key traits of great cyberwarriors.”

Neino, a self-taught programmer who got his first computing job at 15, co-founded Kryptos nine years ago. The firm doesn’t do any marketing and has no salespeople among its 25 employees.

Hutchins said he didn’t ask for a raise after WannaCry because he had just been given one. He wouldn’t say how much he earns, but money goes a long way in Ilfracombe, where one in five children comes from a family whose income is less than 60% of the national average. He said he invests his earnings in stocks and bitcoin, and made thousands of pounds shorting the British currency after the country voted to leave the European Union last year.

Given the nature of his work and his tendency to sound off on social media without much of a filter, Hutchins had kept his online and real-world lives separate.

“No one knew on either side what the other side did,” he said.

Changed forever

WannaCry changed that forever. After registering the domain that Friday afternoon in May, Hutchins posted a link to it online so others could track the attack’s progress. Within a few hours it became clear that WannaCry had stopped self-propagating, and fellow researchers started tweeting that it was @MalwareTechBlog who had saved the day. Pretty soon he was being bombarded with thousands of e-mails and direct messages on Twitter from journalists and security companies wanting to know whether their clients had been infected.

Hutchins knew it was only a matter of time before his identity was blown and admits feeling a little scared.

“Generally, you don’t want to advertise what you’re doing as you don’t want to piss off the bad guys,” Hutchins said. “We published the tracker not knowing we’d foiled it. Had I known that, I wouldn’t have publicised that it was me. Angry criminals are the worst criminals.”

For the next 72 hours, Hutchins went without sleep while fending off ever more aggressive attacks from hackers trying to take his servers offline to disable the kill switch and repropagate WannaCry.

Hutchins thinks that was mostly the work of low-level, semi-skilled hackers referred to in the industry as skids, or script kiddies. They aren’t in it for the money, he said, they just like causing as much trouble as possible.

By Sunday, the British media had identified Hutchins as the man who stopped WannaCry, and the next day he had journalists camped outside his house, 275km from London, stuffing business cards through his letterbox and ringing the doorbell. At one point Hutchins jumped over the back wall of his yard and fled through a car park.

“When I was outed, my parents were pretty shocked and my friends still don’t believe that I have a job,” Hutchins said. “Being unmasked was pretty horrendous.”

Hutchins claims to not like people very much, but he’s affable and engaging. Several times during a walk around Ilfracombe’s harbour and through its narrow streets, friends and acquaintances called out greetings. He chafes at being identified as a hero and said he doesn’t have plans to move, though he did enjoy a recent trip to Copenhagen to give a speech at an industry convention.

“What we did with WannaCry was impressive in terms of the scale of what we stopped, but on a technical level all we did was register a domain,” Hutchins said. “My employer was already paying me way more than I was worth, so the whole WannaCry thing didn’t really change anything.”

Kryptos’s Neino is adamant that Hutchins deserves to be called a hero and warns that everyone should prepare for more attacks.

“We’re going to see a wave of these attacks if Shadow Brokers make good on their promise to release more exploits,” Neino said. “They’ve made good on every other threat, so there’s no reason to think they won’t this time.”

Petya was proof of more to come. After pulling another all-nighter, Hutchins said, he just wanted to go back to bed. — Reported by Gavin Finch, with assistance from Edward Robinson, (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP