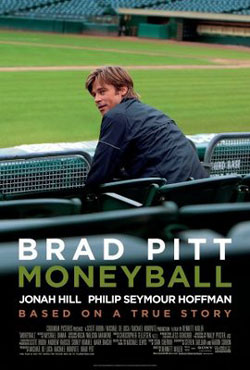

In The Social Network, scriptwriter Aaron Sorkin created a thriller about a geek building a website in a Harvard college dorm. With Moneyball, a new vehicle for Brad Pitt, he fashions a fascinating but uneven sports drama from the arcane topic of how statistical analysis has transformed American major-league baseball over the past 10 years.

At the heart of Moneyball is an idea that will be familiar to anyone who has read Super Crunchers by Ian Ayres or Freakonomics by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner: correctly interpreted, the numbers we collect in electronic databases tell us truths about the world that make a mockery of our common sense beliefs. As much as we want to fall back on intuition and experience, hard and unyielding statistics don’t lie to those who know which questions to ask of them.

Moneyball, based on a nonfiction book of the same name by Michael Lewis, dramatises the conflict between experts who rely on gut feel and experience and the upstart number crunchers who trust only in the trends they uncover in their data sets. This is a development that has the potential to shake the world even more than the social networks Sorkin probed in his last movie.

The film centres on Billy Beane (played by Pitt), the general manager of cash-strapped baseball team Oakland Athletics. Beane has just lost his star players to better-funded rivals at the start of a new season. Without the budget he needs to bid for top-ranked players, Beane is desperate for a new approach to keep his team in the game.

He gets just such an idea from a young Yale-educated economist by the name of Peter Brand, one of the few characters in the film who is not a real person. Brand’s radical thought is that talent scouts and team managers often overvalue or undervalue certain players purely out of personal bias.

Together with Beane, Brand sets out to build a low-budget team by trading off over-rated stars with high batting, base stealing and bunting averages for those that have a good statistical track record for making it to base.

Thus, cheaper players who were overlooked for being too old, too fat or having an unconventional pitching arm were substituted for more erratic performers that scouts liked for their confident manner or textbook technique. Both in the film and in real life, this team of second-rate players rampaged through a 20-game winning streak in 2002.

Thus, cheaper players who were overlooked for being too old, too fat or having an unconventional pitching arm were substituted for more erratic performers that scouts liked for their confident manner or textbook technique. Both in the film and in real life, this team of second-rate players rampaged through a 20-game winning streak in 2002.

Pitt, now beginning to look craggy and worn from age himself, brings a great deal of depth to his role as the quick-tempered and burnt-out Beane. Under the directness of a former jock is the quiet disappointment of a failed athlete trying to redeem himself by leading an underdog team to victory. Jonah Hill’s chunky Brand, the geek that shall inherit the earth, is the perfect foil for Pitt with his mixture of nerdy arrogance and awkwardness.

You don’t need to understand or love baseball to appreciate Moneyball since it is more a story about business and technology than the game. At its heart is a story that plays out in MBA case studies as often as in Hollywood movies: a battle between a poor, scrappy organisation that uses new ideas and technologies to turn the tables on better-funded rivals. This is the part of the film that is most engaging, with Beane’s verbal jousting with his talent scouts showing just how much the new thinking threatens the old order.

Sorkin, an apparent frontrunner to script a Steve Jobs film based on Walter Isaacson’s biography, is becoming Hollywood’s go-to guy for films about technology for good reason. In Moneyball, he shows a knack for making both the number crunching and baseball accessible to viewers who aren’t completely familiar with their intricacies.

Moneyball is not as good as The Social Network, the David Fincher-directed look at the human drama surrounding the founding of Facebook. Though there is plenty of wit, the writing doesn’t zing and crackle as much as the endlessly quotable script for The Social Network.

The direction from Bennett Miller, director of the acclaimed Capote, is thoughtful and leisurely to the point that the film meanders for a good 30 minutes longer than necessary. The sentimental domestic scenes about Beane’s relationship with his daughter, especially, drag a little.

Moneyball trailer (via YouTube):

Yet this is also a film to be praised for its intelligence and depth. It only occasionally falls back on the old baseball film clichés, with its scenes on the baseball diamond mostly cold and clinical. The players themselves are little more than variables in an equation, much like the stats that determine the outcome of a table-top role-playing game.

Perhaps that’s appropriate for a film about how stats wizards with computers and formulas are better at picking winning teams than people with a lifelong love for the game. Unlike most sports films, Moneyball offers victories that are small, fleeting and ambiguous.

Most Hollywood films about technology are either techno-utopian or completely Luddite in outlook. Moneyball is more equivocal than that. Statistics drain the romance and passion from sport, but also banish irrationality. You can rail against the change like the ageing, grizzled scouts that fight Beane’s methods or embrace it. — Lance Harris, TechCentral

- Read more: Meet the real Peter Brand

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Google+ or on Facebook

- Visit our sister website, SportsCentral (still in beta)