In recent weeks, the Prosus team has been working hard to persuade anyone with the time to listen that there was a compelling reason for it to be hived out of Naspers and listed separately on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.

In recent weeks, the Prosus team has been working hard to persuade anyone with the time to listen that there was a compelling reason for it to be hived out of Naspers and listed separately on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.

It’s likely that awarding a really generous remuneration package to the team members and their expensive hangers-on was only part of that reason.

The main reason was to reduce the hefty discount between Naspers/Prosus and Tencent; this, so the story goes, would be achieved by Prosus building up its own attractive portfolio of businesses.

A year is obviously too short a period to determine whether or not the strategy will be successful, but the signs aren’t encouraging. Prosus has failed to secure two eye-poppingly expensive acquisitions (even more expensive now), and the discount has grown.

The grim reality for one-year-old Prosus is that, on the basis of all we know, there is little to no chance its leadership team – no matter how much it’s paid – will weld together a collection of Internet-based investments that could match what is being welded together by Tencent. Even if a lot of the estimated 700-plus companies Tencent has invested in fail, there is still considerable scope for continued great success. And it would be a level of success several times more impressive than the most successful scenario Prosus could hope for.

Global metaverse

Tencent is at the very centre of the global metaverse; Prosus is on the edge trying to pick up scraps.

No matter how fast the Prosus team runs to chase down the discount, the Tencent team will be running considerably faster driving it up.Being the Internet, there might of course be some totally unseen and currently unseeable scenario that could p

lay out in the coming years and make it all worthwhile for Prosus and its shareholders. But without being able to see that, it does seem that right now the best explanation for the existence of Prosus is as a form of insurance.

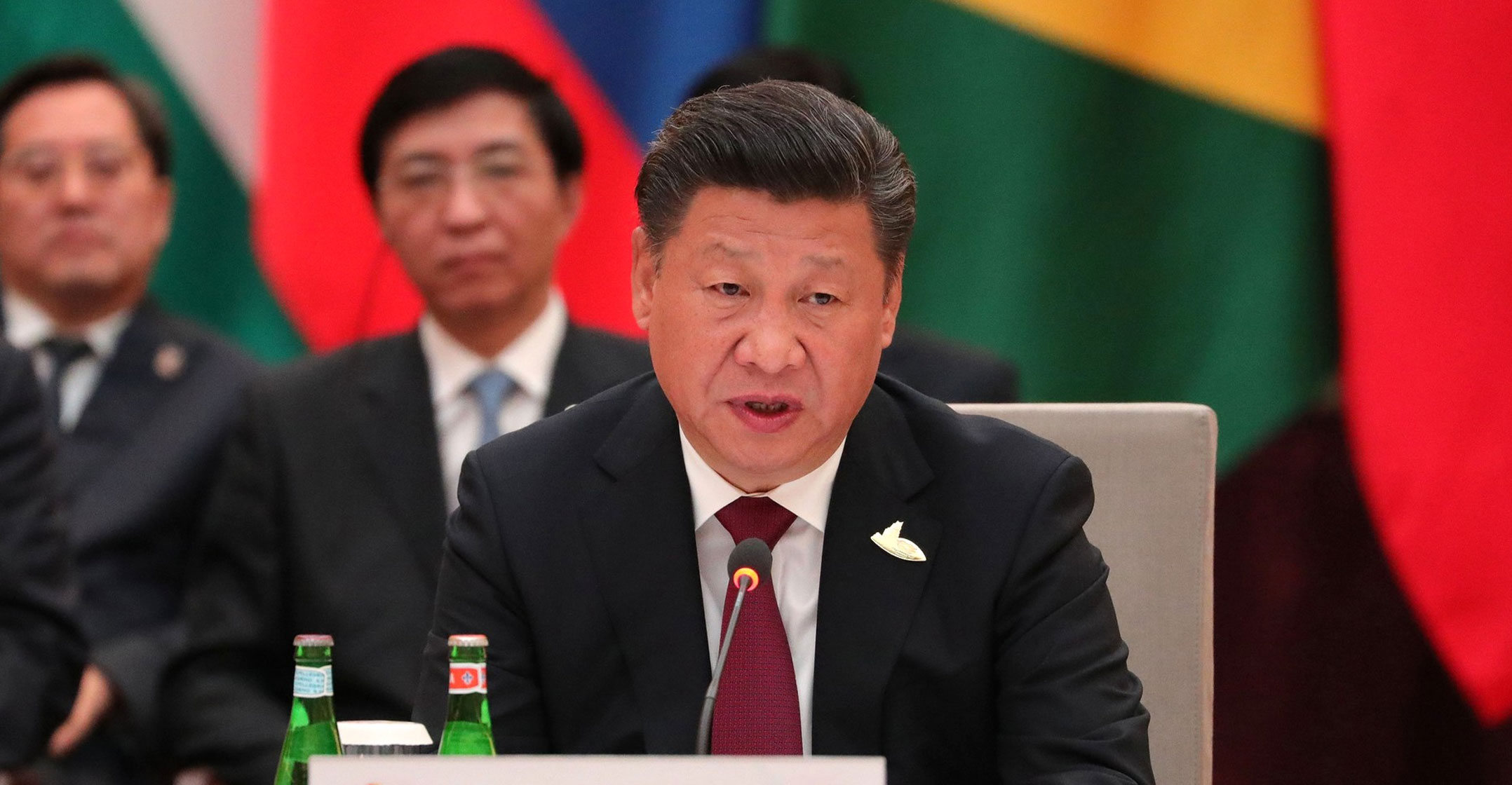

It is insurance against the world as we know it being upended. Insurance against President Xi Jinping deciding one day that China does not need the rest of the world that much after all and opting to challenge the ownership of 31% of one of the country’s most important national champions. That’s the stake that currently rests with Prosus.

That might sound more like a President Donald Trump manoeuvre than something the more grounded Xi would contemplate, but the Chinese president – a noted nationalist – seems increasingly willing to incur the ire of international leaders and pursue what he perceives are his country’s own interests at any cost.

Xi’s inclination to take a tougher stance in the global economy is currently evident in Beijing’s growing use of what was described in a recent Financial Times column as a policy of “coercive commercial diplomacy”. This sees Beijing blocking imports ostensibly because of safety or other concerns, from a country that has displeased Beijing or as a warning not to challenge China’s politics particularly on the Uighurs, Tibet or Hong Kong. Germany, Australia, Canada, Philippines, Japan, Sweden, the UK and Mongolia are some of the countries on the receiving end of China’s coercive commercial diplomacy.

It is, of course, not the first time a powerful economic player has flexed its muscles to secure its interests – that is the story of colonialism as well as a feature of the dominance of the US throughout the 20th century.

Indeed, Trump’s combative approach on Huawei and TikTok – an approach expected to be continued even under a Democratic presidency – is a reminder to China of the scope of tit-for-tat diplomacy.

So, back to Naspers and the (so far) value-destroying creation of Prosus.

The thing is, in a global environment of tense jingoism where enormously valuable hi-tech companies are prized assets, it is reasonable to want to create some insurance against someone grabbing one of those assets.

Prized asset

Tencent is one of the most valuable of those prized assets. It is the world leader in gaming and runs the largest messaging, social networking and mobile payments platform in China. As one analyst recently enthused: “In China, Tencent is like Facebook, Nintendo, Shopify, Netflix, Spotify, Slack and PayPal rolled into one. Its flagship product, WeChat, has 1.2 billion users and those users spend more time in the app every day than Americans spend on all social media combined.”

In his “Not Boring” blog, analyst (and Tencent shareholder) Packy McCormick explains how Tencent turned the profits from its social networking, e-commerce and gaming cash cows into a global investment portfolio that includes many of the world’s most popular videogames, the fastest-growing Internet businesses in China, meaningful stakes in Tesla, Spotify and Snap, as well as a portfolio of international start-up unicorns second only to Sequoia’s. Tencent has proved to be a world-class capital allocator.

While McCormick is, like most analysts, excited about Tencent’s current dominance, it is Tencent’s future that thrills him to hyperbolic levels.

“Tencent is in the best position of any company to usher in and profit from the metaverse, the misunderstood and potentially mega-lucrative evolution of the Internet,” says McCormick. (According to one definition, the metaverse will be an “always-on, real-time world based on the Internet, in which an unlimited number of people can participate at the same time”.)

“Tencent’s structure and strategy – providing capital and traffic – is the perfect model to profit from the decentralised, competitive, creator-friendly ecosystem that the metaverse is likely to be,” says McCormick.

Even if you’re not as robustly enthusiastic about the metaverse as McCormick, even if the future is a very pale version of his metaverse, Tencent is in line to score big time. It has capital and, through its investments, it knows where the market is headed. It can buy into those markets, securing a strong and profitable foothold before competitors.

But here’s the thing: For how much longer will a jingoistic Chinese leadership, in an increasingly hostile global environment, be happy with “foreign” ownership of one of its national champions? Particularly one that is not only hugely valuable but is critical to the government’s ability to keep tabs on its 1.4 billion citizens?

It is important to consider that despite its valuable international investments, Tencent’s ability to exist and flourish relies on the goodwill of the Chinese government. Building some sort of insurance against the possibility, no matter how remote, of China once again turning inwards seems like a reasonable strategy. If anything did happen to Tencent then Prosus would have an asset base that might provide some comfort to Naspers’s shareholders.

Everyone needs insurance

No doubt the present, extremely complex share ownership structure that exists between Naspers/Prosus and Tencent provides some comfort for Naspers/Prosus shareholders – more so given that it is controlled by South African-based private entities in which Koos Bekker is assumed to play a dominant role. Bekker is known to have had excellent relationships with senior Chinese officials over the decades. But he is of an age where insurance is advisable.

It is, of course, all quite dramatic speculation and even four years ago might have seemed fanciful. But Trump, Covid-19 and an increasingly truculent Xi means there is no such thing as certainty in the world of business and politics. Everyone needs insurance.

Still, it’s difficult to understand why they’re paying the puppets at Prosus so much to build a consolation insurance prize.

- This article was originally published by Moneyweb and is used here with permission