In January, the New York Times lost its top spot in comScore’s ranking of the world’s biggest newspaper websites to Britain’s Daily Mail. The Times sniffed at the accuracy of comScore’s figures, which exaggerate the Mail’s online audience by including a personal-finance site that the paper owns. But the battle to be biggest reflects a growing phenomenon: national news publications going global.

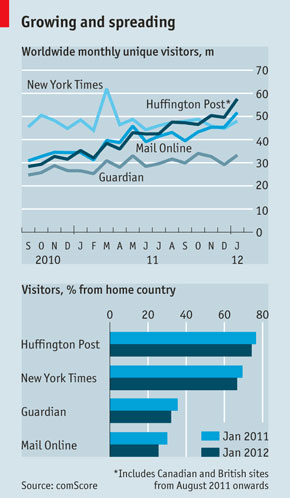

A mere one-quarter of the Mail’s online readers are in Britain. The Guardian, which caters to those who like their news left-leaning and serious in contrast to the Mail’s right-wing raciness, has one-third in Britain and another third in America (see charts). Their chief competitors are two American publications: the New York Times, which like the Guardian aims at readers of serious news, and the Huffington Post, which since its launch in 2005 has become the biggest site of the four (it is not in comScore’s “newspaper” category).

That the HuffPo is beating papers with a history stretching back to the 19th century is a sign of just how differently news works online. The HuffPo is designed for the wired generation’s short attention spans and addiction to social media; alone of the four, it has managed recently to increase its “stickiness”, the number of stories each visitor reads. And it mixes both hard and frothy news (much of it rewritten from other sources, though an increasing amount is original) with generous dollops of opinion by guest bloggers.

This has proved an especially potent formula in America, where the big papers tend to be somewhat po-faced. That is because their dominance in their home cities inclined them towards a neutral stance, to attract the widest possible readerships there, whereas the big British papers, having developed as national outlets, used political leanings to distinguish themselves in a competitive market. Hence, also, the success of the Guardian and the Mail in America. As the Fox News channel discovered earlier, a lot of Americans like their news sources to have a political slant.

The HuffPo and Times are less global than their British rivals, with three-quarters and two-thirds of their readers, respectively, in America. But those proportions, too, are edging downwards.

Global news outlets are of course nothing new: the BBC, CNN and Al-Jazeera, as well as the Financial Times, the Wall Street Journal and indeed The Economist, have long aimed at a worldwide audience, and newswires like Reuters and Bloomberg have big, free online offerings. But in future, argues Ken Doctor, a media analyst at Outsell, a consultancy, there will be fewer national news outlets online. More will either look for new ways to make money from a small local audience, or try to get as big a global one as possible.

The reason is the grim economics of online news. Only a few, business-orientated newspapers are making money by charging readers for access. For most papers, what they publish is too similar to what people can get free elsewhere. Advertising, the other chief source of revenue, is worth far less per reader online than in print. So their best bet for making money is to pull in more readers for the same content.

Cultivating foreign advertisers takes time, however. “We always had a large US audience,” says James Bromley, the MD of the Mail online, “which people used to point to as a weakness because we couldn’t monetise them.” But, he adds, “the marginal cost of the [extra] audience is basically zero, so any ads were a profit.” The Guardian’s ads, too, earn less per reader in the US than on similar American sites, says Andrew Miller, CEO of Guardian Media Group. But they still help the bottom line.

Unfortunately, even a big jump in online advertising will not make up for the decline of print: newspapers’ websites account for a relatively small share of total revenue (about one-fifth for the Guardian, just 2,6% for the Mail). At this stage, it is all about capturing audience. The Mail now has about 30 staff in the US to create stories for its American readers; the Guardian also has 30 in a new bureau in New York, and has experimented with translation, posting some of its Arab-spring coverage in Arabic. Neither seems to think of itself as essentially British any more, at least online. Of the Mail, Bromley says, “Our audiences in the UK and US are more similar to one another than to their neighbours in either place.”

A global strategy that makes obvious sense for papers in English also has potential in other global languages. Spain’s El Mundo lags considerably behind El País in print circulation, but is ahead of it online: 42% of its readers are overseas, and though it sells no print copies in Latin America it is among the top two or three news sites in every Spanish-speaking country there, says its deputy editor, Ignacio Gil. Marca, a sports paper owned by the same company, has a similar reach.

A global strategy that makes obvious sense for papers in English also has potential in other global languages. Spain’s El Mundo lags considerably behind El País in print circulation, but is ahead of it online: 42% of its readers are overseas, and though it sells no print copies in Latin America it is among the top two or three news sites in every Spanish-speaking country there, says its deputy editor, Ignacio Gil. Marca, a sports paper owned by the same company, has a similar reach.

News-gathering on the cheap

Expanding abroad is harder for American publications than for British ones, because most English-speaking markets outside America are relatively small and fragmented. That said, the New York Times has done little recently to appeal to readers overseas other than creating an international version of its home page that gives foreign news more prominence. With its 25 foreign bureaus it has always thought of itself as a global newspaper, says a spokeswoman; its bet is that solid, authoritative reporting will win the day. Even if it wanted to, however, the debt-laden paper can ill afford to increase its already large editorial staff.

By contrast, the much leaner HuffPo can afford to create a network of overseas clones. Since last July it has opened offices and websites in Britain, Canada (in both English and French) and France; it is launching in Italy and Spain this spring; and it is in talks with possible partners in Germany, Greece, Brazil and Japan.

How well the HuffPo model will travel is not yet clear. It owes its success in America not just to its tone but also to its knack for getting readers to contribute lots of unpaid blog posts and comments — hence its low costs. The HuffPo’s British version has a decent if hardly stellar 4,1m monthly unique visitors; but there it competes directly with the Guardian, which serves a similar audience and runs a popular “Comment is Free” blogging platform. (The HuffPo claims to be politically neutral but most of its contributors, like its founder, Arianna Huffington, lean left.)

In much of Europe, blogging is less developed. Le Huffington Post, which launched in France in January, will “open a space for debate” currently limited chiefly to the op-ed pages of newspapers, says its director, Anne Sinclair. And whereas American newspaper editors lashed out at the HuffPo for stealing their stories and poaching their readers (though by linking to their stories it arguably adds to their traffic), their European counterparts think it can teach them new tricks: it has teamed up with Le Monde in France, La Repubblica and L’Espresso in Italy and El País in Spain, bringing them social-media know-how in return for access to their readers. “It’s better to be with them than watching from the outside,” says Louis Dreyfus, CEO of Le Monde Group.

What is at stake for all four of these news giants, however, is very different. The Mail’s print circulation of 2m is second only to that of the tabloid Sun in Britain and is falling more slowly than that of most other papers. It also remains decently profitable. The Guardian and New York Times are losing readers faster, their heavyweight journalism costs more, and although their holding companies recently posted profits, revenues have been falling alarmingly. Both are hoping to increase digital revenues sharply through their tablet and smartphone apps, where readers must pay for news (the Times now charges on its website too; the Guardian does not plan to). Even so, in the medium term they may not be able to sustain their big newsrooms, making it harder to do the journalism that distinguishes them.

Of the four, the HuffPo is the only one unencumbered by old-media technology, staff and institutional baggage. But it has picked up baggage of a different sort since being bought by AOL a year ago. With the dial-up Internet access service on which it was founded shrinking fast, AOL has been trying to build up a display-advertising business by buying lots of websites. This has not gone well. Starboard Value, an investment firm with a stake in AOL, recently estimated that the display-ads business lost the company $500m last year.

Huffington, now in charge of all AOL’s editorial properties, has poured resources into expanding her own creation. As well as the international sites she has launched dozens of subject-specific ones on everything from the environment to weddings. This spring there will be an online television station, featuring continuous studio chat and relying heavily, in true HuffPo style, on viewer contributions.

AOL seems to have given her great leeway, prompting internal grumbles about her empire-building and doubts about how well she and her team can handle such explosive growth. Though the HuffPo was profitable before being bought, its revenue is still a fraction of AOL’s total. As a digital native it is better adapted than its three main newspaper rivals to the online environment — but having the most troubled owner may not do it any favours. — (c) 2012 The Economist![]()

- Image: NS Newsflash/Flickr

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Google+ or on Facebook

- Visit our sister website, SportsCentral (still in beta)