The biopic Oppenheimer works on many, many levels, as one would expect from director Christopher Nolan (Interstellar; Inception; the Dark Knight). It is at once an extended allegory, a sad indictment of human nature, and a testament not only to brilliance and imagination, but also the refusal by the theoretical physicist J Robert Oppenheimer to be bowed by state repression and intransigence.

The biopic Oppenheimer works on many, many levels, as one would expect from director Christopher Nolan (Interstellar; Inception; the Dark Knight). It is at once an extended allegory, a sad indictment of human nature, and a testament not only to brilliance and imagination, but also the refusal by the theoretical physicist J Robert Oppenheimer to be bowed by state repression and intransigence.

Nolan himself is one of Hollywood’s most creative directors – his 2000 film Memento was filmed in reverse – which stands him in good stead to understand the brilliant mind of Oppenheimer, who in this movie, and by all accounts in life, refused to pander to the establishment and compromise his ethical beliefs and loyalty to his colleagues.

The facts of the movie are based on the biography American Prometheus, about the charismatic but complex “father of the atomic bomb” and his efforts to release enormous amounts of energy through nuclear fission, harnessing it into a weapon to end the lingering World War 2 in Japan.

Oppenheimer led a team of international experts at the remote Los Alamos Laboratory in Mexico that developed methods of purifying uranium and plutonium, the latter a metal that only existed in microscopic quantities when Project Y — the secret project to build the first atomic bomb — began.

Oppenheimer had learnt Sanskrit and was said to be influenced by the Bhagavad Gita. As he witnessed the first detonation of a nuclear weapon on 16 July 1945, Oppenheimer is said to have been reminded of a piece of Hindu scripture: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” From the moment the test bomb exploded, he was haunted by the implications for man in the unleashing of the basic forces of the universe.

Leading up to the success of the bomb, he had clashed with various government security apparatchiks and even colleagues with whom he shared close academic camaraderie – people like Ernest Laurence and Edward Teller – but who turned on him when he refused to support the rampant anti-communist sentiment during the peak of the Cold War.

National hero

Immediately after the war, Oppenheimer was declared a national hero, but his questions about the uses to which the bomb could be put led to immediate hostility. One of the men most determined to destroy Oppenheimer’s reputation was Lewis Strauss, a conservative who clashed ideologically with the Atomic Energy Commission’s director. He convinced FBI director J Edgar Hoover to put surveillance on Oppenheimer.

American fears of the Soviet Union were at a high and senator Joseph McCarthy helped stoke a mass paranoia that communists were infiltrating the US after the war ended. Oppenheimer fell from grace after the Atomic Energy Commission alleged he had ties to communism and revoked his security clearance in 1954.

Many of Oppenheimer’s associates in the years before World War 2 were Communist Party USA members, including his wife Kitty – whose second husband Joe Dallet had been killed fighting in the Spanish Civil War – Oppenheimer’s brother Frank, Frank’s wife Jackie, and Oppenheimer’s girlfriend, Jean Tatlock. But Oppenheimer was not. His refusal to abandon his friends and deny his allegiance to liberal thinking nevertheless led to a rigged and abusive official hearing into his activities. As a result, his security clearance was revoked – and thus his inability to continue work for the AEC.

The film is long and complex, with many of the techniques Nolan habitually employs: quick cutaways, flashbacks and frequent time transitions. Visually, it is exciting and sometimes almost overpowering, with huge explosions filling the screen to symbolise the protagonist’s vision. The musical score by Swedish composer Ludwig Göransson is every bit as compelling and at times of tension, the insistent repetition of the violin in the orchestra makes it impossible to think of anything other than the mounting urgency unfolding on screen. At the moment of the test bomb’s explosion, however, there is dead silence, adding to the impact of the full-screen visual of flames and dust clouds and rolling explosions through the desert air.

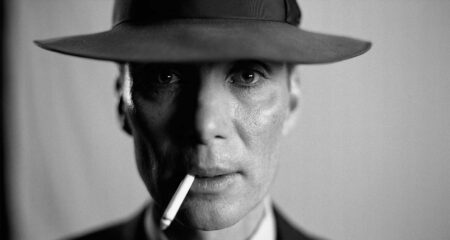

The stellar cast of Cillian Murphy as Oppenheimer (a mainstay in many of Nolan’s movies ), Emily Blunt as his wife Kitty, Matt Damon as Gen Leslie Groves and Robert Downey as Strauss never disappoints. Murphy infuses the languid, erudite statements made by his character with quiet derision at times, which helps to explain why he attracted some of the hostility he did from characters like Strauss, who exemplifies the petty, self-seeking ambition of a career politician.

Much has been made of Nolan’s statement that he is telling the Oppenheimer story because he sees it as a “cautionary tale”. He says he sees parallels between the early nuclear age and the dawn of the AI era in ours.

Oppenheimer’s calls for international nuclear arms control faced stiff resistance from the US, which feared losing sovereignty, and there are similar concerns with artificial intelligence, Nolan believes.

“The way tech companies transcend geographical boundaries , often in very aggressive ways, makes it very difficult to regulate AI on a sovereign national basis,” Nolan told the FT Weekend of 23 July. “Clearly this is something that needs to be regulated.”

Ultimately, however, the movie is about the complex and ambiguous nature of one of the greatest men of our time, who despite his brilliance and moral introspection, was also naïve, a womaniser, temperamental and whom Truman, US president at the time, called a “cry baby”.

At three hours, it’s an intense experience, but Oppenheimer is a movie every bit as brilliant as its subject matter. – © 2023 NewsCentral Media