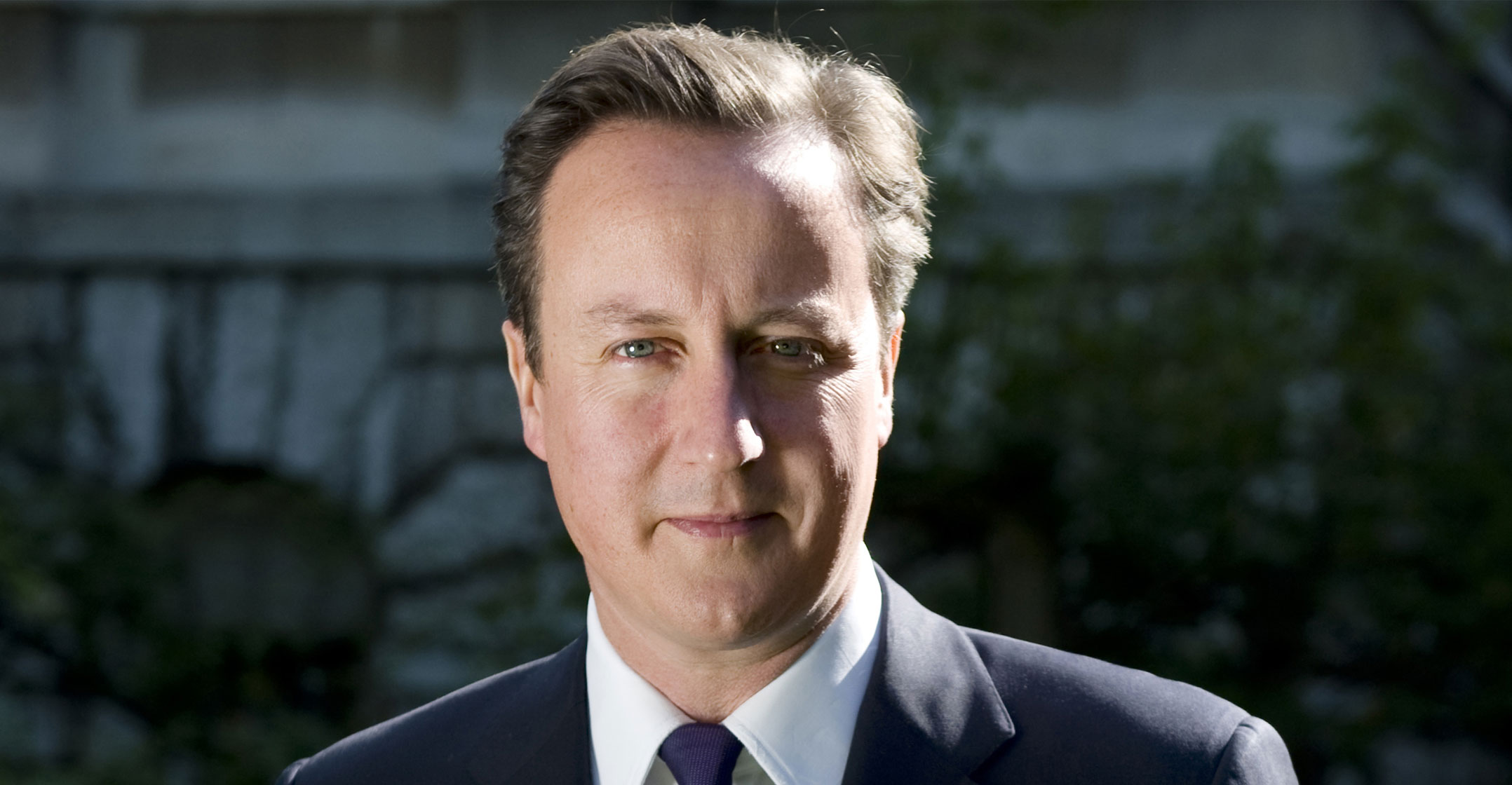

David Cameron’s work for Greensill Capital, which has dragged the British government into a high-profile lobbying scandal, has showcased the growing trend of politicians taking jobs at companies tapping the global tech investment boom.

The former prime minister, who resigned in 2016, is also chairman of the advisory board at artificial intelligence company Afiniti. Darktrace, the British cybersecurity company that filed to go public this week, counts former home secretary Amber Rudd on its advisory council, alongside the ex-head of intelligence agency MI5. Nick Clegg, former deputy prime minister, has worked at Facebook since 2018.

Where finance and investment banking were once obvious go-to places for those looking at life after Westminster, software companies, fintechs and app developers have become the highly popular alternative option.

Finance is still a draw — former chancellor George Osborne is at takeover advisors Robey Warshaw after a stint at BlackRock — but the tech sector is luring more politicians, ministers and civil servants keen to be part of the IT-driven fourth Industrial Revolution.

“It’s a trend of tech companies being more dominant in the UK economy, being faster growing, being more interesting,” said Leo Ringer, a former UK government adviser and founding partner of Form Ventures. While it’s right that there are questions when senior government advisers join the private sector, “in the vast majority of cases, those questions can be answered fairly clearly,” he said.

Revolving door

The revolving door between government and business is in the spotlight after it emerged Cameron lobbied ministers on behalf of Greensill, which collapsed earlier this year. The growing controversy has led to the launch of multiple inquiries into lobbying and rules of conduct.

At Afiniti, Cameron sits alongside ex-CEOs, the former Pakistani Ambassador to the US and retired US Navy admiral Mike Mullen on the 17-member body, which doesn’t have any fiduciary duties. The company makes technology that it says can pair customers with the call centre workers most likely to solve their problems. Beatrice York, Queen Elizabeth II’s granddaughter, is listed as Afiniti’s vice president of partnerships and strategy.

Afiniti CEO Zia Chishti said the company benefits from a “diverse array of senior business and political leaders”.

“Each one has made a significant mark in their field and I have great respect for their achievements,” Chishti said, adding on Cameron: “We value his contribution enormously and he has our full support.”

The company said the former prime minister hasn’t lobbied the government on its behalf.

High-profile positions:

- Clegg was hired by Facebook in 2018 as vice president of global affairs;

- Darktrace made a number of high-profile additions to its council last month including Lord David Willetts, a former universities & science minister;

- Faculty Science, a London-based artificial intelligence firm that’s worked on the National Health Service’s coronavirus response, counts former public officials in its leadership, including chief operating officer Richard Sargeant, who previously worked at the home office, and chief commercial officer John Gibson, who spent a decade in government work, including the prime minister’s policy unit; and

- Thea Rogers, the fiancée and former chief of staff to George Osborne, is now the chief customer officer at Deliveroo.

Representatives for Facebook, Deliveroo, Faculty and Darktrace declined to comment.

Others have also backed or championed tech firms. Uber Technologies had senior former politicians on its side when it was fighting to keep its licence to operate in London. The Evening Standard newspaper published an editorial while Osborne was editor, bashing a 2017 decision to suspend the ride-hailing giant’s licence in the city.

Health secretary Matt Hancock controversially endorsed British healthcare app Babylon in a health supplement in the Evening Standard in 2018, which was sponsored by the company.

While prime minister, Cameron’s government set up a body that was supposed to help police lobbying. The UK also has the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments, or Acoba, which offers advice to former government ministers and senior civil servants on new jobs.

But neither group has enough power to be effective, said Alex Thomas, a programme director at the Institute for Government and a former senior civil servant.

Acoba “only really works for those who want to comply with the rules, and therefore doesn’t really have any teeth at all”, he said, suggesting the advisory-only body should have a legal underpinning.

Narrower probe

The opposition Labour Party had demanded a full parliamentary inquiry into the lobbying scandal, but lawmakers rejected that in a vote this week. Prime Minister Boris Johnson has instead initiated a narrower probe.

“There has been a series of incidents where the modest constraints and ethical oversight that exist in the British system has been able to be brushed away over last 18 months or so,” Thomas said. “It comes down to the extent to which the prime minister is up for recognising that it’s in the government’s own interest to clean up shop a little bit.”

Karthik Ramanna, a professor at Oxford University specialising in business-government relations, said any response should acknowledge that the public and private sector can benefit from each other.

“What you don’t want is people abusing their political connections to short-circuit what would otherwise be good government policy,” he said. “The solution is never to blanket-ban these things because there’s a more benign explanation. And in fact there is some value to having that public sector expertise in business.” — Reported by Thomas Seal and Ivan Levingston, (c) 2021 Bloomberg LP