No one wanted Steve Jobs when he was born, writes Alistair Fairweather. His biological father was a young Syrian professor at the University of Wisconsin, his mother a graduate student. Her family would not allow them to marry and she was forced to give him up for adoption in the bitter February of 1955, a few days after his birth.

His adoptive parents, Paul and Clara Jobs, were solid, working-class folk. Paul was a high-school dropout who made a living as a machinist, Clara an accountant. They lived in Mountain View, California, an agricultural community at the southern end of the San Francisco Bay.

At the time no one would have guessed the significance of Mountain View and the surrounding towns that we now call Silicon Valley. Hewlett and Packard had founded their company in a garage in nearby Palo Alto in 1935, but it had not yet become the global titan it is today.

Into this nascent revolution dropped an inquisitive, fearless and irrepressible young boy, the kind of kid who could convince his parents to move towns so that he could attend a better high school.

At the age of 12, he phoned William Hewlett, now the head of one of America’s largest companies, to ask for advice on a gadget he was working on. Hewlett promptly offered the impudent tyke a job on his assembly line. Jobs was thrilled.

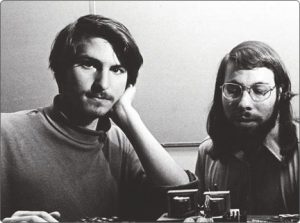

It was during a summer job at Hewlett-Packard that Jobs met the other Steve — Wozniak — the technical genius who would co-found Apple Computer Company with him in 1976. Following in his adoptive father’s footsteps, Jobs had dropped out of college to pursue a wild dream: selling fully assembled PCs.

The gamble paid off handsomely: by the mid-1980s, Apple had become a global brand. But in 1985, internal strife at the company had reached such a pitch that Jobs felt he had no choice but to resign in disgust. He was just 30 years old.

‘Picking up Jobs’

Though Apple languished under a series of lukewarm leaders, shrinking in both profitability and influence, Jobs picked himself up and promptly started two other revolutions.

In 1986, recognising that animation would eventually be computerised, he helped found Pixar. By 2000, the company had grown into one of the most successful animation studios of all time, second only to Disney.

His other company, NeXT Computer, was less obviously successful, but achieved two things: it created a software platform on which many of Apple’s products still rely and it was acquired by Apple.

Within a matter of months, Jobs was appointed “acting chief executive” of Apple. Suddenly, after more than a decade, he was at the helm of his own company again.

And not a moment too soon. By the late 1990s, Apple was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy and collapse. In typical fashion, Jobs quickly drew together a group of creative and technical geniuses and began to transform the company from within.

The early fruit of this renaissance, the brightly coloured Apple iMac, was a huge success, bought as much for its beautiful design as its capabilities. And so, a new template for Apple was born: beautiful, desirable, functional.

From this point on the history of Apple has entered modern folklore. First came the iPod, then the iPhone and now the iPad, reinventing markets, delighting customers and terrifying competitors with every new step.

We all knew that Jobs was ill. In 2004, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, but battled through it and a subsequent liver transplant in 2009, taking only relatively short leaves of absence. At annual Apple events he appeared at times to be frighteningly gaunt. His resignation in late August 2011 was not completely unexpected.

But few believed he would, or even could, die. For many fans of Apple, Jobs had attained a messianic quality, a god of technology who could be both benevolent and cruel. Even those unaffected by his reality distortion field cannot quite believe this vivid genius is no longer with us.

Above all, what Steve Jobs taught the world is to believe. Through sheer hard work and a stubborn refusal to bow to the conventions of reality, Jobs changed the world not once but three times. His companies and products have delighted and inspired hundreds of millions.

When he died peacefully on Wednesday this week, he was surrounded by his family. But around the world, his adoptive family, the legions of Apple and Pixar fans, were there in spirit.

No one wanted Jobs when he was born, but, 56 years later, everyone wanted him to live. — Alistair Fairweather, Mail & Guardian

- Alistair Fairweather is digital platforms manager at the Mail & Guardian

- Visit the Mail & Guardian Online, the smart news source

- Top image: Acaben

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Facebook