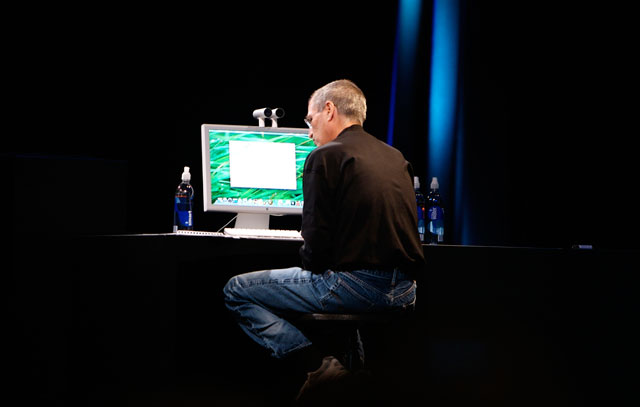

In another example of how good Steve Jobs was in picking technology losers and winners, in 2010 he listed all of the reasons why the world needed to move on from using Flash. At the time, Jobs was explaining why the iPhone and iPad would not support Flash but it is clear that if he could, he would have banned it from the desktop.

In 2009, Symantec had declared Adobe’s Flash as having one of the worst security records, an honour that Adobe has unfortunately done little in the intervening years to change. For Jobs, as bad as the security issues were, they weren’t the only reason he didn’t like Flash. He cited the constant browser and system problems caused by Flash and the fact that apps developed using Flash technologies would never look as good as apps developed directly for the Apple platform.

In its place, Apple was going to use video playing support that was being provided directly by browsers as part of a new standard called HTML5.

Four years later and Adobe is still patching security vulnerabilities. The latest came earlier this month and it had tech companies and their customers scrambling to update installed versions of Flash. This particular vulnerability came to light after a Google engineer showed how the fault could be exploited to steal people’s logon details.

Jobs’s decision not to support Flash on any of Apple’s mobile devices was followed by Google in 2012 deciding not to support flash on Android. Adobe had finally accepted that the standards-based HTML5 was going to be the way video would be displayed in the future, effectively allowing companies to bypass the use of Flash.

Given the fact that the tech industry, and even to a certain extent Adobe itself, has acknowledged that Flash is not their preferred technology, it is worth asking why it would still be so prevalent today. There are a number of reasons for this but unless the tech industry takes an active stance to do something about the use of Flash, it is likely to be with us for some time to come.

Flash is still in use today for two main reasons. The first is to do with the reach of Flash support across browsers that still don’t support the alternative HTML5 video. The second is to do with inertia in industries that have built their businesses around this technology, specifically, the advertising and browser game developers.

The transition to modern browsers is a slow process held back by consumers who never bother to update and businesses and organisations who only update in four- to seven-year cycles. For this reason, there are still a large number of people using browsers that don’t support HTML5 video, like Internet Explorer 8 and earlier versions of the Microsoft browser.

Advertising companies have invested much effort over the past decade in producing interactive and attention-grabbing ads based on Flash technology. So much so, that its pages seem unusually static when these ads are not present, something you can do with Flash or ad-blocking extensions to browsers. Again, there will be little incentive for these companies to move away from this technology on the desktop at least as long as they can justify the use of Flash because of its reach and cost.

The same is true for companies like Disney, which runs sites like Club Penguin, a popular children’s game site written in Flash.

The only way in which users are driven to adopt technology, and this includes upgrading to new versions, is if it is made easy for them and that if there is an incentive to do so or a disincentive not to. It is becoming easier to live without Flash, but until sites like YouTube take definitive steps to end support for this technology, there will be little incentive for those organisations and users who are delaying taking action in upgrading to a browser that doesn’t need Flash.

It is a pity that Apple’s Jobs didn’t push to rid the desktop of what is an ongoing source of security vulnerabilities for computer users. It is not too late, however, for someone in the tech sector to finish that particular task for him.![]()

- David Glance is director of innovation at the faculty of arts and director of the Centre for Software Practice at the University of Western Australia

- This article was originally published on The Conversation