Richard Peng didn’t get to become one of China’s most accomplished dealmakers by pussyfooting around. In 2013, the Tencent acquisitions chief took a shine to a scrappy little ride-hailing app called Didi. He tracked down reluctant founder Cheng Wei and after several conversations lured him into his office. Then he locked the door.

“Buddy, first of all, I know you don’t want our investment,” Peng told him, knowing Cheng once worked for Tencent’s nemesis, Alibaba Group. “Secondly, I have to invest.”

It took hours, a dramatically sweetened offer and the promise of a meeting with Tencent’s billionaire founder Pony Ma, but Peng sealed the deal that would become his signature investment. Didi Chuxing eventually morphed into the US$34bn behemoth that drove Uber Technologies out of China.

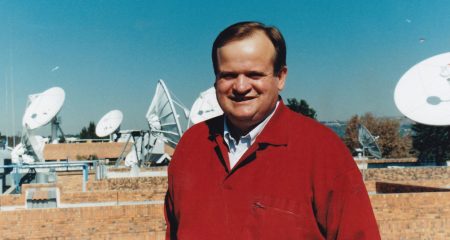

Peng’s deal-making moxie set the pace for a hard-charging Tencent Holdings in its early days. He became one of the most instrumental lieutenants to Ma during a seven-year stint at the $280bn operator of WeChat, during which he helped define China’s largest social media company by orchestrating about $20bn of deals through hundreds of investments and transactions.

Now, the 46-year-old is prepping his second act. Peng’s resume helped him get Genesis Capital off the ground in 2015 and amass more than $450m from backers including Temasek Holdings’ Pavilion Capital and International Finance Corp. His goal remains finding the next billion-dollar start-ups, typically with a China focus. Genesis already manages about a dozen investments, among them e-commerce startup Xiaohongshu or “ Little Red Book” and Uber-for-trucks app Truck Alliance.

But striking out on his own means the stakes are higher. Genesis Capital remains in its infancy, and it’s going up against a stellar roster of like-minded investment houses, from Hillhouse Capital to Sequoia’s Chinese offshoot. While Peng maintains ties with his former employer, he can no longer dangle the prospect of Tencent’s billion-plus users and enormous market clout to entrepreneurs. His war chest is a mere fraction of what he’s accustomed to. And every mistake will count.

“The requirement for return on investment at our new fund is much stricter. We have fewer bullets, so we need to have accuracy and less tolerance for error,” Peng said, speaking in characteristically booming, rapid-fire fashion. “We either make it big or fail miserably.”

Peng’s departure from Tencent continues to befuddle some of his closest friends, but the financier maintains it was a gamble well worth taking. Dressed in baggy jeans one size too big and sporting a backpack, he paced back and forth near a Starbucks on a recent afternoon conducting a conference call. He apologises a half-hour later for the holdup, an urgent talk with one of his portfolio companies.

Peng’s road-warrior tempo sets the pace for Genesis Capital, which requires companies to sign term-sheets the same day it extends an offer to avoid price manipulation. Two of its most recent deals were signed at midnight. His team of about 10 people get paid based on the entire fund’s performance, to ensure everyone chips in. Abandoning the shotgun-approach he favoured at Tencent, Peng today cites the analogy of digging a single well deep enough that it hits water, instead of sprinkling money in batches to hedge against misses.

That doggedness was evident from youth. Peng still speaks with a hint of a lilting Jiangxi accent, reminiscent of a penurious rural origin — he was one of nine children born to a farming family. Giving up vocational school, which would have meant he could start making money earlier, Peng chose instead to go to high school. As neighbours looked on during one tense family meeting, Peng convinced his father: “All my life you’ve told me to be someone and do something important with my life. This is what I want to do now.”

That set Peng on a path to what seemed at the time a normal academic and business career. He got into Beijing’s Tsinghua University — alma mater to Xi Jinping and countless other party cadres — where he sought inspiration through the writings of Alvin Toffler and business icons Armand Hammer and Lee Iacocca. He became something of an entrepreneur: early penny-ante undertakings included bicycle repair and finding work for construction workers.

One of his earliest jobs was at the Shanghai stock exchange, a plum posting he forsook in 2001 to attend the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. After getting his MBA, Peng joined Samsung Group before leaving in 2005 to become Google’s first local Chinese hire. He parted ways with the search giant in 2008 to join Tencent — a company then one-sixteenth the US company’s size.

“He was always trying to find something to do, always full of ideas and energy,” said Andy Lin, a former colleague at the exchange and founder of Loyal Valley Innovation Capital. “Very idealistic, but also practical enough to execute his plans.”

After joining Google, Peng oversaw the expansion of its then-nascent local advertising business. He gained a reputation for winning over reluctant clients, demonstrating a talent for dealing with people. Instead of cutting straight to a sales pitch, he would listen to clients complain, find out what wasn’t working — often the merchants had set up wrong keywords or landing pages for their ads. He’d then follow up with suggestions and ask them whether they’d be open to another trial. More often than not, they agreed.

“It’s very similar to investing in start-ups. You need to get to know them, assess them and then sign them up on your platform, know what they need. You need to provide them support, and give them training,” said Peng. “Because I was dealing with very grassroots, small businesses, it helped me understand business in China better.”

That personal touch continues with portfolio companies like artificial intelligence-focused DataVisor. When executives from the US fraud protection company visit China, Peng makes the effort to fly three hours from Hong Kong to Beijing to spare founders such as Xie Yinglian time.

Tencent president Martin Lau took notice of Peng when he was at Google, recruiting him to lead a fledgling mergers and acquisitions team. One of the earliest decisions was a decree that the company would avoid taking controlling stakes so as not to affect founder incentive.

In subsequent years, the deals Peng’s team put together — from Riot Games to e-commerce giant JD.com and search engine Sogou — helped build both Tencent’s content library and its user base. Didi was his career-defining moment: Cheng, the founder, was seeking a valuation of about $40m at the time so Peng offered money at a price tag 50% higher. Today, Didi is China’s second most valuable start-up. Cheng declined to comment when contacted through the company.

“Richard essentially helped Tencent build its merger and acquisition team from the ground up and helped shape its culture,” said Chen Shaohui, chief strategy officer for Meituan Dianping, another of Tencent’s signature deals. The former executive director at Tencent’s investment division worked with Peng for four years. “People were all very surprised by his decision to leave such a coveted role, but that’s Richard, always persistent and looking for challenges.”

To be sure, not all of Peng’s investments panned out. Tencent spent a significant amount on Fab.com — one of the most epic flame-outs dotting the US start-up landscape. Chiam Fong Sin, chief operating officer of Pavilion Capital, said in an e-mail that Peng has been one of the most prolific and successful investors not just in China but globally, yet emergent themes from AI to health care mean fund managers will need to adapt to changing dynamics.

“His role investing for Tencent was very different from what he’s doing now,” said Li Muzhi, a Hong Kong-based analyst at Arete Research Services. “At Tencent, investments are made for strategic positioning and not missing out on new trends, whereas now the requirements for financial return will be much higher.”

That could be a challenge. Peng warns of an imminent industry shake-up, in which some of the largest players (he wouldn’t name any) may be forced to take funding at lower valuations or even implode. With foreign direct investment dropping and the country losing the benefits of ample cheap labour, Peng reasons that China may have to seek growth by revamping traditional sectors such as retail through technology.

That’s why finding the right people is crucial. He divides founders into those that can create $1bn, $10bn or $100bn companies, placing them into a three-by-three grid that evaluates everything from intelligence to tolerance and critical thinking. The questions Peng asks them appear random — he could spend an hour chatting about topics unrelated to their business, prodding them about social trends or their upbringing.

“We need to figure out who they really are,” Peng said. “We challenge them and question their business plan’s viability to test whether they have belief in what they’re doing, whether they have drive — and whether they think.” — (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP