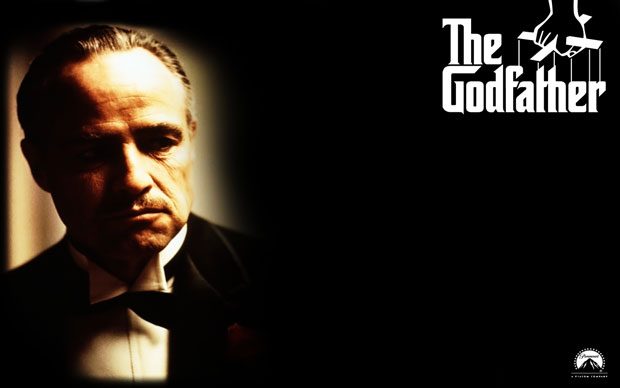

Is any other film ageing as gracefully as The Godfather, which celebrated its 40th anniversary in March this year? Francis Ford Coppola’s mafia saga is as compelling now as it was then, a film that perfectly fuses a director’s personal vision with epic themes and that effortlessly reconciles artistic flair with cracking entertainment.

The Godfather is one of the greatest achievements of the new Hollywood — a movement of the late 1960s and 1970s that saw young directors such as Martin Scorsese, William Friedkin and Robert Altman wrestle creative control of their movies away from the studios. It was born out of the tension between the old studio system that treated directors as hired hands and the new pack of auteur-brats.

That the film exists in the form it does is a miracle. Made by a green director with only some work for trash merchant Roger Corman on his CV and based on a best-selling potboiler by Mario Puzo, there was no reason to imagine at the outset of production that The Godfather would become one of the best films of all time.

Paramount turned to Coppola to direct The Godfather after a number of name directors rejected its overtures. The studio initially wanted spaghetti Western maestro Sergio Leone or Peter Bogdanovich, at that time hot from his success withThe Last Picture Show, to direct the film.

Coppola, just in his early 30s, eventually got the job partly on the strength of his Sicilian and Italian heritage. Robert Evans, head of Paramount, said that he “wanted to smell the spaghetti” in the movie. Studio bosses also thought that Coppola’s youth and inexperience would make him pliable.

How wrong they were. Coppola’s frictional relationship with Paramount and Evans especially would become the stuff of Hollywood legend. The director spent most weeks of the six-month shoot waiting to be fired after fighting Paramount honchos on everything from budget and casting to the underlit look of the interiors and the setting in the 1940s.

Nearly every element of The Godfather that has become iconic represents a battle that Coppola won against Evans and other Paramount heads. Rather than Al Pacino, Paramount fancied Robert Redford, Warren Beatty, Alain Delon or Ryan O Neal for the part of criminal empire heir Michael Corleone.

As laughable as it may sound, Paramount wanted Ernest Borgnine rather than the notoriously chaotic Marlon Brando for the role of the ageing mob patriarch Vito Corleone. The studio wanted to update the action to the 1970s; Coppola insisted on staying in the era of the novel, despite the added costs period detail would add to the production.

As Peter Biskind recounts in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls — his definitive account of the rise and fall of the new Hollywood — Paramount suits hated the “dailies” they saw from the film. Executives complained that they couldn’t make out what was going in the dark interior scenes and moaned that they would need subtitles to understand Brando’s mumbled dialogue.

Somehow, despite the reservations that Paramount had about the film, it escaped into the wild as the animal that Coppola had given birth to. The reception from critics was ecstatic. They raved about the performances, the script and the weighty themes with which the film grappled. But The Godfather was not only an artistic triumph, but also a smash hit at the box office.

Though Jaws is usually regarded as the milestone that marks the start of the blockbuster era, The Godfather paved the way. In an unusual move for a time when films were rolled out in theatres over months, The Godfather opened in around 350 cinemas across the US simultaneously. The film revived an ailing Paramount with an immediate transfusion of cash, pumping an unprecedented US$86m into its cash flow by the end of its first run.

So what explains The Godfather‘s enduring appeal? Perhaps it’s the fact that it is as classically elegant in its storytelling as it was innovative and revolutionary in some of its casting and technical choices. At its heart, The Godfather is a timeless American story of wealth, power and family that has been described as Shakespearian in its character arcs.

There is also little doubt that despite the grand themes — the corruption of the powerful and the betrayal of the American dream — this was also an intensely personal film for Coppola. A middle child with a fraught relationship with his family, Coppola connected with the sibling rivalries and the stifling patriarchy of the Corleone family. There’s a hint, perhaps, of the relationship between the new Hollywood directors and the studio bosses in the conflicts with Vito.

Nearly every scene is a master class in filmmaking. In just two minutes, starting with the sting of the ironic words “I believe in America”, Coppola tells us everything we need to know about poor Italian migrants in New York and their status as undertaker Bonasera begs the Godfather for justice for his badly assaulted daughter.

Every scene that follows is as pithy and pacey, so that The Godfather never feels overlong despite its spacious three-hour running time. Scenes like the nail-biter where Michael moves his badly wounded father to a different room in a hospital as gunmen descend, and the one showing Sonny’s operatic death, still thrill, despite the many times they have been copied. The period setting is meticulous but understated. The Godfather is a film that seldom feels the need to belabour a point.

And although its dialogue has seeped into popular culture — “It’s strictly business”; “Luca Brasi sleeps with the fishes”; “Make him an offer he can’t refuse” — it is still so sharp and caustic in context that it retains its bite. No film before or since illustrates Balzac’s axiom as vividly: “Behind every great fortune there is a crime.”

Despite the fact that so many of the scenes are shrouded in dark at a time most Hollywood films were flooded with light, the composition of most shots in The Godfather is fairly conventional. Where Coppola uses tight zooms — as in the opening shot of the undertaker’s face — or overhead shots, like the god’s eye view of Vito’s shooting, it is done with intelligence and purpose.

Of course, there’s the acting. The Godfather not only netted a best actor Oscar for Brando (who ungraciously declined it), but best supporting actor nominations for Pacino, Robert Duval, and James Caan. The godfather Don Vito is the lead character of the book, but in Coppola’s treatment it is Michael Corleone who is arguably the protagonist. The young Pacino carries the film on his shoulders, colouring it with the sort of nuance and understatement that has become rarer in the actor’s performances as he has grown older.

At first, he is deeply convincing as the idealistic war hero who has stayed out of the family racketeering business. But in the pivotal scene, where he decides to go to war on his father’s behalf, the ruthlessness he inherited from Vito bursts to the surface. Pacino makes you realise that the mercilessness was always there, but you just didn’t see it before.

Behind the scenes (via YouTube):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VQFrnnueZ2c&feature=player_embedded

He gives no speeches about the inner turmoil as the two sides of his nature battle each other, but the scars of the struggle write themselves on his face. The moment where Michael Corleone orders the death of his brother in law is chilling. The vacuum in Pacino’s eyes makes it clear that Michael has lost his soul.

Brando’s Don Vito is barely corporeal, often little more than a voice rasping from a face barely visible through darkness as thick as pea soup. He is a shade, a man hollowed out by his pursuit of wealth, a pure will to power. It is only his family that that keeps him tethered to the world of humanity. His ominous presence casts a shadow on every scene in the film. Caan as the hot-headed son Sonny and Duval as the quiet, outsider adoptive son Tom also turn in career-best performances.

In The Godfather‘s success were also the seeds of the new Hollywood’s destruction. Coppola, flush from success with The Godfather and The Godfather 2, became increasingly megalomaniacal and puffed with hubris. Like many his fellow new Hollywood directors, he made increasingly extravagant demands on both his audience and the studios in the films he made.

The famous Godfather theme by Nino Rota (via YouTube):

Coppola started principle photography for Apocalypse Now in 1976, a shambolic shoot that dramatically overshot its budget and schedule after the director insisted on heading to the Philippines during monsoon season. His next major film — One from the Heart — was a self-indulgent mess that made only $390 000 in its first weekend on a budget of $26m. It bookended the new Hollywood and marked the start of the next studio blockbuster era.

But the legacy of The Godfather lives on everywhere in popular culture. It is credited with “The Godfather Effect“, clearing the way for proudly ethnic films from Italian Americans and other cultural groups.

It has inspired every gangster film since, but only Coppola’s Godfather 2, Scorsese’s Good Fellas and Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America rival it in stature. The American Film Institute ranks it only behind Citizen Kane andCasablanca in its pantheon of the all-time greats of American cinema.

Read more:

Time magazine: 40 things you didn’t know about The Godfather

Pauline Kael’s review of The Godfather in The New Yorker (1972)