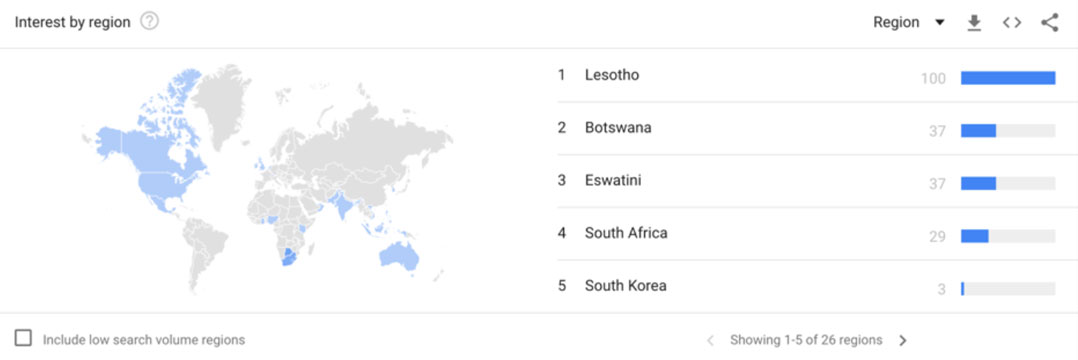

Deputy President David Mabuza is not the only one having difficulty defining the term “fourth Industrial Revolution”. A search on Google trends will show that no one else in the world is talking about it, except of course, South Africa and its neighbours. Figure 1 below shows worldwide interest in the term “4th Industrial Revolution”, or 4IR, over the past 12 months.

Deputy President David Mabuza is not the only one having difficulty defining the term “fourth Industrial Revolution”. A search on Google trends will show that no one else in the world is talking about it, except of course, South Africa and its neighbours. Figure 1 below shows worldwide interest in the term “4th Industrial Revolution”, or 4IR, over the past 12 months.

The reason behind the confusion behind this term is that as a model, the fourth Industrial Revolution is a bit flaky. In 2011, Jeremy Rifkin announced the emergence of the third Industrial Revolution as new communication technologies converge with new energy regimes. Barely five years later, another luminary, Klaus Schwab announced the fourth Industrial Revolution as new technologies start fusing the physical, digital and biological worlds. Really? Two earth-shattering revolutions in five years, without the subsequent positive impact on the economy? An Internet search will show widely different definitions of the third Industrial Revolution, not even to mention widely diverging interpretations relating to the fourth.

It is a self-evident that technology is changing our world, our knowledge base, our means of production and our society. The key question is what foundation our technology categorisation is based on. Is it now up to well-known individuals to announce the commencement of a new industrial revolution? If this is the case, I am eagerly awaiting the announcement in early 2020 of the fifth Industrial Revolution by either Kanye West or Christine Lagarde.

Creating simplified models to try to explain complex environments has been a hobby of humankind ever since the start of the spoken word. The key problem with classification frameworks is that once we apply the categorisation, distant nodes in a network can be clumped together, while nodes that are in close proximity are artificially separated.

Inherently wrong

The problem is, categories matter if they influence policy decisions that affect people’s lives. Although all models superimposed on complex adaptive systems are inherently wrong, some are useful. We need to focus on those that are the most useful for the circumstances we face.

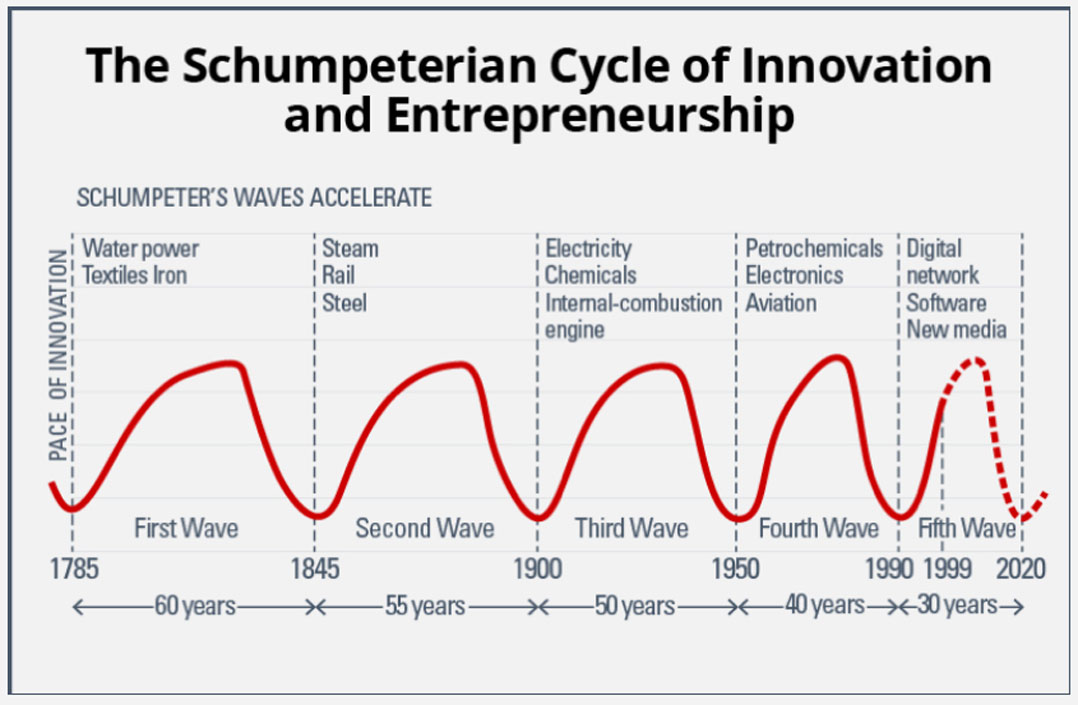

The discourse around the impact of technology on a country’s economy is of critical importance. It is therefore wise to choose your point of reference carefully. It can be argued that the most important insight in this field was first highlighted by Nicolai Kondratieff in 1925. This Soviet economist was the first to bring these observations to international attention in his book, The Major Economic Cycles. The famous Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter in 1929 suggested naming the cycles “Kondratieff waves” in his honour (see figure 2 below).

The key to the success of the Kondratieff waves was that each of these waves were measurable in the economy at large. The historian Eric Hobshawn commented: “That good predictions have proved possible on the basis of Kondratieff Long Waves — this is not very common in economics — (and) has convinced many historians and even some economists that there is something in them.”

Kondratieff identified three phases in the cycle, namely expansion, stagnation and recession. More commonly today is the division into four periods. The commonly known phases were redefined as the spring, summer, autumn and winter of each Kondratieff wave. Common wisdom, although not universally shared, is that we are currently in the autumn of the fifth Kondratieff wave. The linkage of energy and manufacturing systems with communication technology is but a logical conclusion of the information revolution that became influential in the early 1980s. Calling it a third or fourth Industrial Revolution may be good for books sales, but it is doubtful if it has any foundational value other than establishing a strong meme to sell tickets to conferences.

If we use Kondratieff waves to create a model of the future, a few interesting scenarios emerge. Using the Kondratieff wave as a model on a globally integrated economy suggests that we may have to brace for a severe winter in the next few years. This winter will be amplified by immense debt in most wealthy countries and a dramatic decline in affluent 25-year-olds that normally power our global consumption economy. The winter of the fifth Kondratieff wave may follow the path of creative destruction (a term coined by Schumpeter). Numerous large organisations may go bankrupt, at the same as new, agile companies emerge to fill the void in a changing competitive landscape.

The start of the sixth Kondratieff wave is a matter of significant debate. Will it be the use of the Higgs Boson Vector, the last piece of the Standard Model discovered, that may lead to the software-based design of new materials? Will it be to use CRISPR CAS9 and other DNA manipulation techniques to open an era of human-defined evolution? Will it be a focus on our DNA and microbiome to redefine health care as opposed to our current “sick care” system? Will we use new transport systems to redefine the cost of logistics? Will it be a renewed interest in quantum entanglement to drive everything from quantum cryptography to quantum radar? What will drive the sixth Kondratieff wave, and when will it start? No one knows with certainty. A growing body of economists are speculating about the validity of these long-term waves as quantitative easing and negative interest rates overturn established economic models.

The policy decisions that are informed by our categorisation of technology is critically important. Focusing on increased production efficiency is significant in the autumn of the Kondratieff waves. Focusing on business model experimentation (using platform technologies to alter user behaviour in periods of economic distress) can be argued to more effective in the winter of the Kondratieff waves. Primary R&D focused on groundbreaking new technologies is better served at the advent of spring in the Kondratieff waves.

Irrelevant of which lens we use to classify the technologies that permeate our lives, we should, however, be able to detect its impact on economic growth. The focus of a revolutionary model is not on incremental growth based on the increased efficiencies of established industries, but rather the emergence and explosive growth of new sectors of an economy driven by revolutionary new technologies. Maybe significant economic growth should be at the heart of the foundation of the models that we use to plan our future, rather than the whims of influential authors and those that follow them blindly.

- Pieter Geldenhuys is the director of the Institute for Technology Strategy and Innovation and guest lecturer at the London Business School

- This article was originally published by Moneyweb and is used here with permission