The mid-level bureaucrats left China’s richest man waiting as they prepared for a meeting that would send shockwaves across the financial world.

It was Monday morning in Beijing, and Jack Ma had been summoned to the China Securities Regulatory Commission just days before he was set to take Ant Group public in the biggest stock market debut of all time.

When the regulatory officials finally entered the room where Ma was waiting, they skipped over pleasantries and delivered an ominous message: Ant’s days of relaxed government oversight and minimal capital requirements were over. The meeting ended without a discussion of Ant’s IPO, but it was a sign that things might not go as planned.

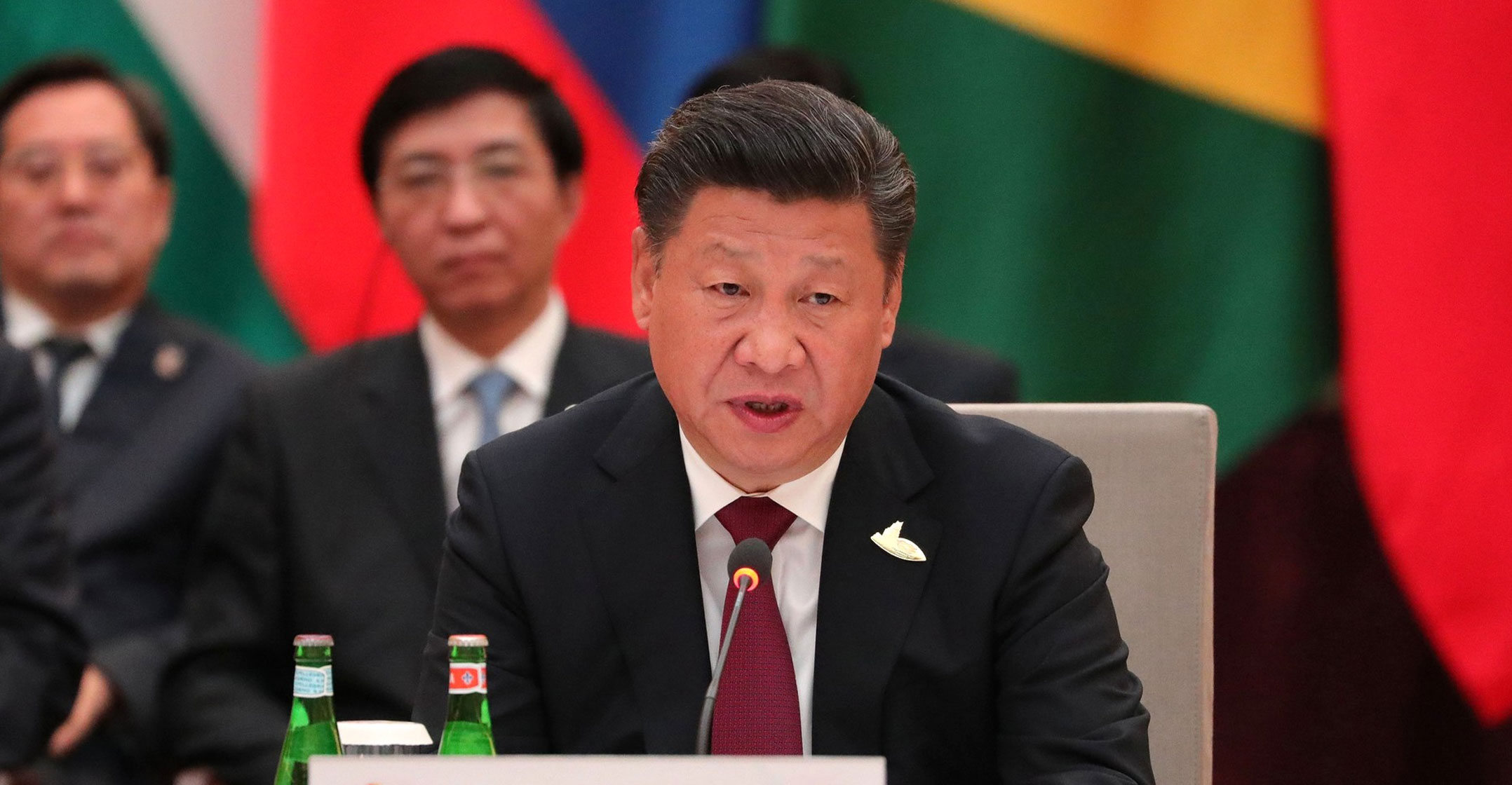

The subsequent unravelling of the US$35-billion share sale has thrust Ma’s fintech giant into turmoil, offering a stark reminder that even China’s most celebrated businessman isn’t immune to the whims of a Communist Party that under Xi Jinping has steadily tightened its grip on the world’s second largest economy.

Among the questions that linger as international investors try to make sense of a chaotic 72 hours: Why would China scuttle Ant’s IPO at the last minute after months of meticulous preparation? And what does the future hold for one of the country’s most important companies?

Interviews with regulators, bankers and Ant executives offer some answers, though even insiders say only China’s top leaders can be confident of what happens next. Most of the people who spoke for this story did so on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters.

Scramble

Ma’s meeting in Beijing on Monday triggered a behind-the-scenes scramble by Ant and its bankers for more clarity from Chinese regulators. While CSRC officials signalled at the time they weren’t aware of any changes to the IPO plans, the regulator’s cryptic social media post later that day about a “supervisory interview” with Ma set tongues wagging from Hong Kong to New York.

By Tuesday afternoon, the mood had worsened as whispers of a delay began circulating in Shanghai. At around 8pm, the city’s stock exchange called Ant to say the IPO would be suspended.

When the official statement landed less than an hour later, it cited a “significant change” in the regulatory environment but offered few additional details on why authorities would scupper the listing two days before shares were expected to start trading.

At a hastily arranged meeting between Ant’s bankers and the CSRC later that evening, officials pointed to the company’s need for more capital and new licences to comply with a spate of regulations for financial conglomerates that had begun taking effect at the start of November. There was no discussion of how quickly the IPO could be restarted.

One concern among regulators was that the stricter rules may not have been fully disclosed in Ant’s prospectus. On top of the new financial conglomerate regulations, the government had on Monday released stringent draft rules for consumer loans that would require Ant to provide at least 30% of the funding for loans it underwrites for banks and other financial institutions. Ant currently funds just 2% of its loans, with the rest taken up by third parties or packaged as securities.

Several officials said it was better to stop the listing at the 11th hour than to let it proceed and expose investors to potential losses.

That sentiment was shared by at least one institutional money manager, who said he had practically begged an Ant executive for an IPO allocation during a meeting at the Mandarin Oriental hotel in Hong Kong. Now that he has a clearer idea of the regulatory risks, he’s relieved the share sale was shelved. The CSRC said in a statement on Wednesday that preventing a “hasty” listing of Ant in a changing regulatory environment was a responsible move for the market and investors.

Still, some China watchers have an alternative theory for why Xi’s government acted the way it did: It wanted to send a message.

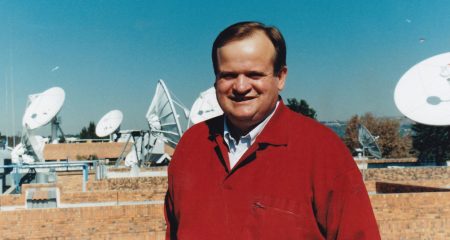

Ma, a former teacher who’s widely revered in China, faced an unusual amount of criticism in state media after he slammed the country’s financial rules for stifling innovation at a conference in Shanghai on 24 October. His remarks came after vice President Wang Qishan — a Xi confidante — called for a balance between innovation and strong regulations to prevent financial risks.

Open defiance

“It appeared that, intentionally or not, Ma was openly defying and criticising the Chinese government’s approach to financial regulation,” Andrew Batson, China research director at Gavekal Research, wrote in a report.

The weekend before Ma was summoned to Beijing, the Financial Stability and Development Committee led by vice Premier Liu He stressed the need for fintech firms to be regulated.

In one sign authorities may keep up the pressure on Ant, people familiar with the matter said on Wednesday that regulators plan to discourage banks from using the fintech firm’s online lending platforms. The directive strikes at the heart of Ant’s commission-based lending model, which generated about 29-billion yuan ($4.4-billion) of revenue in the six months ended June.

Any suggestion that banks will stop using its platforms is unsubstantiated, Ant said in a response to questions.

Some investors are bracing for tougher times at both Ant and the rest of Ma’s business empire. Shares of Alibaba Group, which owns about a third of Ant, tumbled more than 8% on Tuesday in New York for the steepest drop in five years. The slump cut Ma’s wealth by almost $3-billion to $58-billion, dragging him down to number two on China’s rich list behind Tencent’s Pony Ma.

The IPO debacle has also raised broader concerns about China’s commitment to transparency as it tries to lure international investors.

On Tuesday, confusion over the suspension triggered a flood of calls to Ant’s bankers from baffled money managers. The sense of whiplash in some cases was stark: Just an hour or two before the suspension was announced, Ant’s investor relations team was still trying to confirm attendance at a post-IPO gala in Hong Kong. One of the company’s biggest foreign investors predicted the episode could do lasting damage to confidence in China’s capital markets.

It may also have spillover effects on Hong Kong, whose status as a premier financial hub has already come under question amid increased meddling from Beijing. Nearly a fifth of the city’s population by one estimate had signed up to buy Ant shares; many who had planned on a windfall were instead stuck paying interest expenses on useless margin loans.

“The lack of transparency reminds us that the ‘Chinese way’ remains fraught with issues,” said Fraser Howie, author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundation of China’s Extraordinary Rise.

Risks

As for Ant itself, it’s unlikely that the IPO suspension will deal a fatal blow. The company had 71-billion yuan of cash and equivalents as of June and is one of China’s most systemically important institutions. The last thing authorities want is a destabilising loss of confidence in a business that plays a key role in the nation’s financial plumbing.

The more pertinent risk for Ant is a decline in its breakneck pace of growth and lofty valuation. China’s new regulations will force the company to act more like a traditional lender and less like an asset-light provider of technology services to the financial industry. That will almost certainly mean a lower price-earnings ratio for the stock if it eventually lists.

Also looming is the introduction of China’s central bank digital currency, which threatens to erode Ant’s dominance in payments. That could have implications for the company’s other businesses as well. Ant’s credit platform, for instance, utilises its huge trove of payments data to assess the financial strength of borrowers who often lack collateral or formal credit histories.

All of that will be bad news for shareholders who propelled Ant’s valuation to $315-billion — higher than that of JPMorgan Chase & Co. But it may suit regulators and party leaders who worry that Ma’s creation has grown too big, too fast. — (c) 2020 Bloomberg LP