When Paulina Sliwinska, a fund manager at Edinburgh-based Baillie Gifford & Co, made the trip to Silicon Valley looking for the next big thing in technology, she found it — not in a hot start-up run by a 23-year-old whiz kid just out of Stanford, but in a 23-year-old semiconductor maker that’s had the same chief executive since its founding.

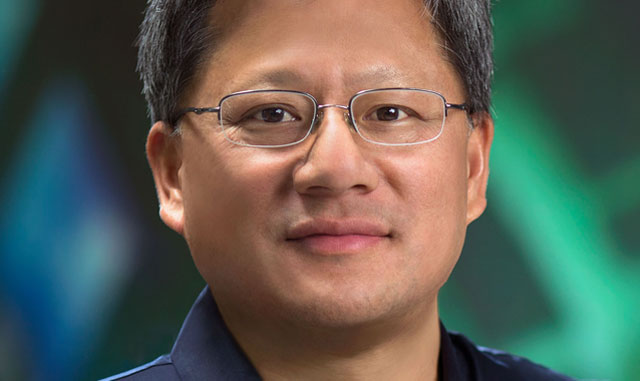

Jen-Hsun Huang, CEO of graphics chip maker Nvidia, has won over Sliwinska and many other investors this year with claims that his products, once confined to the niche of computer gaming machines, are breaking out to become key components of nascent technologies from voice recognition to self-driving cars.

“He’s so engaging,” said Sliwinska. “Even from this point the opportunities in front of it over the next 10 years are astonishing.”

After she met Huang in August, the fund added to its position and is now the 10th largest holder. The company is the best performer on the Nasdaq 100 Stock Index this year, outpacing the number two stock by a multiple of almost three.

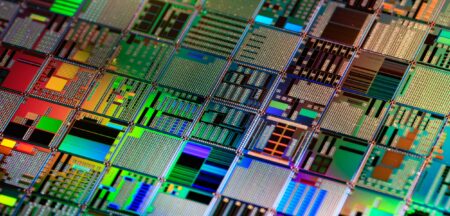

Under Huang, Nvidia has built itself into the leading supplier of graphics processors, the chips that deliver the ever-more-realistic images that make computer games so immersive and addictive. For most of its history, that’s been a relatively small market, with the much bigger businesses of computer processors and smartphone chips dominated by Intel and Qualcomm.

This year, though, Huang’s longtime belief that the fundamental advantages of his graphics chips would give them a broader role in fast-growing fields such as artificial intelligence and self-driving cars has begun to pay off — and is buoying Nvidia’s earnings. In the third quarter, demand for chips used in data centers and cars helped fuel a 54% surge in sales, and profit doubled to a record.

That performance was the result of years of investment in the hardware and software aimed at enabling computers and cars to think for themselves, according to Huang. The stock surged 30% on 11 November, the day after the earnings report. Yet there was no victory lap from the CEO — his company is going to battle in markets also targeted by famously fierce rivals Intel, whose annual R&D spending is twice Nvidia’s revenue, and Qualcomm, which has the largest cash balance in the chip industry.

“The only thing we can guarantee is the velocity with which we innovate,” Huang said in an interview at the time. Nvidia declined to make Huang available for comment for this story.

Huang, 53, runs Nvidia like it’s still a start-up, making snap decisions and demanding fast execution, according to those who have worked for him. For a semiconductor maker, that’s no small feat: designing a chip, getting it ready for market and then having it manufactured can take years and costs hundreds of millions of dollars. Chip companies publish road maps that reflect those intricate details, and they build their organisations around it. Decisions on what to make in multibillion-dollar plants requires extensive planning.

At Nvidia things can happen a lot faster. In the space of a short meeting hosted by Huang, an executive trying to give an update on progress of a new chip design might find himself silenced as Huang calls an engineer to check on a technical question — then instantly decide the project’s dead or make the call to head in a different direction.

Huang has long clung to the belief that graphics chips would play a key role in technological innovation. But past efforts to spread their use, such as in phones, have failed to catch on or taken a lot longer to deliver tangible results.

While the annual advent of a new high-end GeForce chip from Nvidia has long been viewed as a gift from above for computer gamers — many of whom think nothing of paying more for one component than most ordinary users would for a whole computer — Nvidia as a company had been less revered in general until this year. Its stock has struggled to rise higher than US$35 in the 17 years since it first went public. The shares closed just above $105 on 20 December.

Some investors and analysts who follow Nvidia the most closely have missed that run-up. The reason: they’ve heard Huang’s pitches before — such as when he was touting the company’s future as a provider of smartphone chips — and initially wrote off his predictions about artificial intelligence and self-driving cars as no different from previous forays that fizzled.

“Jen-Hsun didn’t dial it up or dial it down — he was just as enthusiastic about the automotive opportunity as he was for Tegra,” said Ian Ing, an analyst at MKM Partners, referring to the company’s mobile phone chip, first announced in 2008.

The Tegra line of chips was Nvidia’s attempt to get into smartphones, which Huang correctly pointed out were on the cusp of transforming computing and communication. Yet because he and others underestimated the importance of an integrated cellular connection, Nvidia’s offering failed to win significant business.

Unlike other companies that lost out to Qualcomm, Huang didn’t close down the project — instead Nvidia fielded its own game console, called Shield, as a way to try to create a market for Tegra and showcase its abilities to potential customers. While Shield never challenged the dominance of Xbox or PlayStation, the product led to orders for Tegra from Nintendo, which made the chip the heart of one its new game systems.

“It was more or less a science project internal to Nvidia, and now Nintendo has adopted it,” said Kevin Cassidy, an analyst at Stifel Nicolaus & Co. “That’s another example of them pulling themselves up by their bootstraps, creating a market and then giving it to their customer.”

Little sleep

The CEO gets little sleep, even on holidays, because he stays up late into the night reading everything he can get his hands on that concerns Nvidia and its businesses, no matter the language — he is fastidious about translations, which he has staff ready to deliver whenever he needs them. While founding Nvidia and building it into the largest maker of graphics chips has made him a billionaire, he still runs the company with the paranoia and drive of someone scared it might fail at any moment, according to those who have worked for him.

In public he speaks in soft tones, using careful pauses for emphasis and employing Silicon Valley’s patois to answer specific questions with broad, lofty discussions that contain grand assertions. Within the company, he has little patience for subordinates who aren’t making the grade and will call them to scream whenever he deems it necessary.

The way he describes it, Huang has always been fighting the bigger guy. He likes to tell the story of how his Taiwanese parents sent him to be educated at what they thought was a private school in the US when he was a child. The institution in Kentucky turned out to be more of a reform school, where he was one of the smallest guys in a rough environment having to get by on his wits and form alliances with the big kids.

Huang’s grown-up bête noire, Intel, is located just across the 101 freeway, which runs the length of California’s Silicon Valley. This other Santa Clara-based chip maker is also the world’s largest. Analysts who in the past have been unwilling to bet on Huang’s vision and execution have cited Intel’s ability to build other computer functions into its processors as an existential threat to Nvidia.

Indeed, Nvidia’s chipset business disappeared almost overnight when Intel decided to build that technology into its products, starting in 2008. Still, Intel has never fielded a graphics chip good enough to persuade high-end computer users to switch from Nvidia. And now Huang’s company is trying to muscle in on the rapidly growing market for chips used in data center servers, Intel’s most profitable business.

Data flood

Traditional data centres are stacked with machines powered by Intel’s most expensive server chips, and many would-be competitors have been trying to break Intel’s lock on the market. Now, the flood of information created by connected devices and online services is overwhelming conventional computing’s ability to analyze and put this data to use. Based on work Nvidia has been doing for several years, graphics chips are increasingly being programmed to run artificial intelligence systems that can perform tasks such as recognising images and speech lightning-fast, without the help of humans.

While Intel processors are extremely fast at performing complex operations, they have a limit in terms of their ability to perform multiple tasks at the same time. That’s where graphics chips have started to make inroads with their ability to perform a much larger number of smaller tasks in parallel. Google and Amazon.com offer graphics-chip-based computing as part of their cloud services. While graphics technology is making headway, the majority of data centre work is done by Intel’s microprocessors and there are efforts by suppliers of other types of chips to tailor their less-power-hungry products for the market. For now, investors think Nvidia is leading efforts to provide the main engine for artificial intelligence.

“They’re in one of the hottest spaces,” said Daniel Morgan, a fund manager for Synovus Trust Company. “You’d have to put them at the top of the list right now. They seem to be positioned really well.”

In its most recent quarter, Nvidia’s data centre revenue, at $240m, was up from just $82m a year earlier. But that’s barely scratching the surface of a market where Intel has more than 99% market share in processors. The larger company’s server chip business delivered more than $2bn in profit on $4,5bn of sales in its latest quarter.

In cars, one of Huang’s passions, Nvidia is aiming to provide the computing engines that will someday make vehicles better than humans at driving. While Tegra is used to run entertainment systems, Nvidia has produced more powerful graphics chips to do the work of taking inputs from radar, cameras and other sensors to build an electronic picture of what’s going on around the vehicle. There’s no shortage of competition from other chip makers, though, and last year Nvidia didn’t make it into the list of top 10 providers of silicon to automakers. One chip maker that did, NXP Semiconductor, last year bought another, Freescale Semiconductor. Now that combined company is being acquired by Nvidia’s mobile nemesis, Qualcomm.

The Nvidia CEO’s willingness to make rapid changes of direction has already manifested itself in cars. Once famous for his love of Ferraris, Huang is now posting pictures of himself on his driveway surrounded by Teslas. Probably no coincidence: the first new version of his complete computer for self-driving cars was delivered personally to Tesla CEO Elon Musk, and Nvidia’s technology is the basis for Telsa’s next version of its driver-assistance technology. — (c) 2016 Bloomberg LP