The dispute over South Africa’s social grant system and threatening millions of vulnerable beneficiaries with non-payment creates risks that go far beyond interrupting poor people’s access to desperately needed grants.

The failure of the South African Social Security Agency (Sassa), which is responsible for the payment and administration of social grants, to act timeously has created a crisis that threatens to deliver grant recipients on a silver platter into the hands of unscrupulous financial services companies.

The latest instalment in the bizarre saga came last week. Sassa officials announced that they would file papers with the constitutional court proposing that their invalid contract with Cash Paymaster Services (CPS), which holds the contract for grant distribution, should be extended for another year.

This contract was awarded to CPS in a controversial tender in 2012. It was declared invalid two years ago by the constitutional court, which instructed Sassa to reissue the tender. As the deadline came closer, civil rights groups such as the Black Sash started sounding warning bells that Sassa was not implementing the court’s orders.

Deadline after deadline passed, and by end the end of 2016 it was clear that Sassa had failed to act on the court’s instructions. Late last week, it appeared that Sassa had missed another one. It didn’t make its planned eleventh-hour submission.

This means that there is no credible arrangement in place to ensure that social grants will be paid when the court’s deadline expires on 31 March. The social grant system supports about 17m individuals. Disrupting the payments will cause huge suffering to the country’s poorest and most vulnerable people and is likely to lead to social unrest.

With last week’s announcement, it seems that Sassa officials intended simply to present the constitutional court and the national treasury with an impossible situation: condone an illegal contract, or face the possibility of social and political chaos.

But there’s even more at stake. If the court allows a further extension of the invalid contract (or approves a new contract with CPS), Sassa will have perpetuated a situation in which the accounts of grant recipients have in effect become mere conduits between the South African fiscus and the private financial empire that has taken shape around grant disbursement.

At the centre of the storm is CPS, originally a small financial services company. CPS is a subsidiary of Net1 UEPS Technologies, a listed global financial services and logistics group with operations in several countries including South Africa, India and Tanzania.

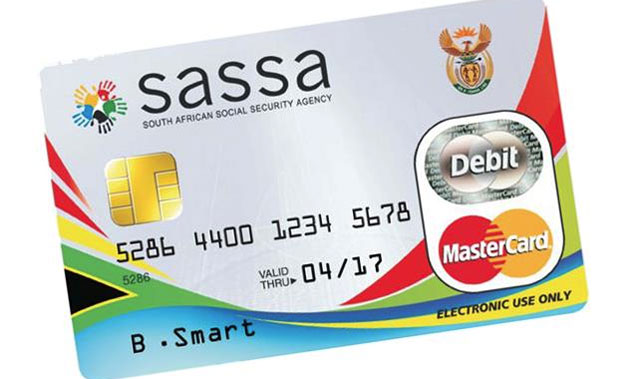

Net1 owns the fingerprint-based biometric identification and payment system that is central to CPS’s operations. Their proprietary Universal Electronic Payments System technology forms the “backend” of the Sassa smartcard CPS uses in the electronic payment of grants. It is access to this system that has enabled CPS to roll out payments to the whole country.

While convenient for CPS, scholar Keith Breckenridge has pointed out that this creates an unprecedented situation: grant beneficiaries are captured within a private technological and financial network owned and controlled, not by Sassa, but by its service provider.

Here it should be noted that the work of CPS is only part of a bigger corporate strategy. Also part of Net1’s global empire are financial services companies like MoneyLine, EasyPay, Manje Mobile Solutions, Smart Life and others. These companies act in concert to make use of the opportunities afforded by CPS’s control of the payment network.

Millions of grants beneficiaries, for example, have not only been provided with a Sassa account; their accounts have also been linked to EasyPay Everywhere, a bank account operated by MoneyLine and CPS’s banking partner, Grindrod Bank. All this is part of an explicit two-stage strategy on the part of Net1: a first wave in which it rolls out its technological infrastructure, and a second wave in which it uses this infrastructure to market a wide array of products and services to an essentially captive customer base.

The net effect is that social grant recipients are now tied up in a web of dependency on financial services companies controlled by Net1.

Financial inclusion

This creates two problems. Firstly, this arrangement may be in violation of competition law. It looks as if Net1 is making use of CPS’s privileged position as social grant paymaster to give its sister companies first bite and privileged access to a vast potential client base.

Secondly, it raises an issue that’s often forgotten in sweeping generalisations about the need to cover the “unbanked” with financial services. Yes, poor people need access to banking services, and may benefit from smartcards and electronic banking. But these services should be designed with their interests in mind.

Deborah James and Dinah Rajak have shown how in South Africa the history of “credit apartheid” and paternalistic control over poor people’s finance has created a situation where creditors wield disproportionate power. Unbridled financial inclusion of the poor may amount to adverse incorporation into a financial sector geared towards preying on them. Already, the Black Sash has collected evidence of troubling instances of unauthorised and unlawful deductions from accounts set up for grant recipients, often with very little recourse.

This is why the social grants crisis has implications beyond the distribution of payments. Sassa has missed a major opportunity to ensure that financial inclusion happens in a beneficial, “pro-poor” way. It failed to follow the constitutional court’s order that the payment of social grants should be done in a way that protects the rights, interests and confidential data of grant beneficiaries.

Instead, it has created a situation in which CPS and Net1 hold all the cards. At present, the constitutional court and national treasury have almost no leverage to prevent their service provider from simply walking away on 1 April 2017.

Already, Net1 CEO Serge Belamant has made it clear that he is not interested in extending the contract on its present terms. He is in a position to ask for whatever he wants — including provisions that lock claimants even more tightly into his empire.

Sassa’s inaction has created the worst possible outcome, not only in the short but also in the long term. A crisis over grant distribution looms, and the opportunity to provide meaningful financial inclusion has been missed.![]()

- Andries du Toit is director of the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape

- This article was originally published on The Conversation