WikiLeaks has released what it claims is the largest leak of intelligence documents in history. It contains 8 761 documents from the CIA detailing some of its hacking arsenal.

WikiLeaks has released what it claims is the largest leak of intelligence documents in history. It contains 8 761 documents from the CIA detailing some of its hacking arsenal.

The release, code-named “Vault 7” by WikiLeaks, covers documents from 2013 to 2016 obtained from the CIA’s Centre for Cyber Intelligence. They cover information about the CIA’s operations as well as code and other details of its hacking tools including “malware, viruses, trojans, weaponised ‘zero day’ exploits” and “malware remote control systems”.

One attack detailed by WikiLeaks turns a Samsung Smart TV into a listening device, fooling the owner to believe the device is switched off using a “fake-off” mode.

The CIA apparently was also looking at infecting vehicle control systems as a way of potentially enabling “undetectable assassinations”, according to WikiLeaks.

One of the greatest focus areas of the hacking tools was getting access to both Apple and Android phones and tablets using “zero-day” exploits. These are vulnerabilities that are unknown to the vendor, and have yet to be patched.

This would allow the CIA to remotely infect a phone and listen in or capture information from the screen, including what a user was typing for example.

This, and other techniques, would allow the CIA to bypass the security in apps like WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, Wiebo, Confide and Cloackman by collecting the messages before they had been encrypted.

If it is true that the CIA is exploiting zero-day vulnerabilities, then it may be in contravention of an Obama administration policy from 2014 that made it government policy to disclose any zero-day exploits it discovered, unless there was a “a clear national security or law enforcement” reason to keep them secret.

Another potentially alarming revelation is the alleged existence of a group within the CIA called Umbrage that collects malware developed by other groups and governments around the world. It can then use this malware, or its “fingerprint”, to conduct attacks and direct suspicion elsewhere.

According to WikiLeaks, this is only the first part of the leak, titled “Year Zero”, with more to come.

WikiLeaks’s press release gives an overview on the range of the hacking tools and software, and the organisational structure of the groups responsible for producing them.

WikiLeaks hasn’t released any code, saying that it has avoided “the distribution of ‘armed’ cyberweapons until a consensus emerges on the technical and political nature of the CIA’s programme and how such ‘weapons’ should [be] analysed, disarmed and published”.

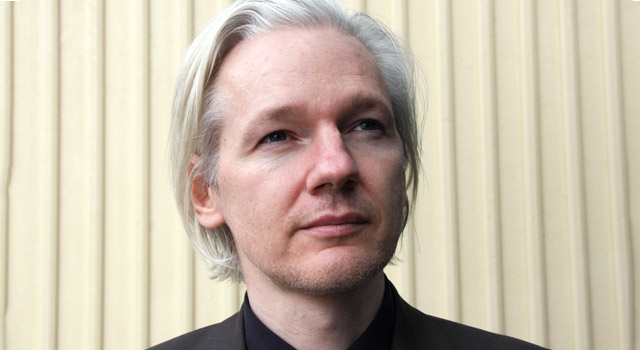

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange made a statement warning of the proliferation risk posted by cyberweapons: “There is an extreme proliferation risk in the development of cyber ‘weapons’. Comparisons can be drawn between the uncontrolled proliferation of such ‘weapons’, which results from the inability to contain them combined with their high market value, and the global arms trade. But the significance of ‘Year Zero’ goes well beyond the choice between cyberwar and cyber peace. The disclosure is also exceptional from a political, legal and forensic perspective.”

There hasn’t been time for there to be any validation that what WikiLeaks has published is actually from the CIA. But given the scale of the leak, it seems likely to be the case.

WikiLeaks has indicated that its “source” wants there to be a public debate about the nature of the CIA’s operations and the fact that it had, in effect, created its “own NSA” with less accountability regarding its actions and budgets.

This release of documents from the CIA follows on from a much smaller release of some of the NSA’s “cyberweapons” last year. In that case, the hackers, calling themselves the “Shadow Brokers”, tried to sell the information that they had stolen.

At the time, it was thought that this hack was likely to be the work of an insider but could have also been the work of the Russian secret services as part of a general cyber campaign aimed at disrupting the US elections.

This release also follows the release of NSA documents by Edward Snowden in 2013.

While WikiLeaks may have a point in trying to engender a debate around the development, hoarding and proliferation of cyberweapons of this type, it is also running a very real risk of itself acting as a vector for their dissemination. It is not known how securely this information is stored by WikiLeaks or who has access to it, nor how WikiLeaks intends to publish the software itself.

WikiLeaks has redacted a large amount of information from the documents — 70 875 redactions in total — including the names of CIA employees, contractors, targets and tens of thousands of IP addresses of possible targets and CIA servers.

Damage done

The damage that this release is likely to do to the CIA and its operations is likely to be substantial. WikiLeaks has stated that this leak is the first of several.

How the CIA chooses to respond is yet to be seen, but it is likely to have made Julian Assange’s chance of freedom outside the walls of the Ecuadorian Embassy even less likely than it already was.

The fact that the CIA would have an arsenal of this type or be engaging in cyberespionage is hardly a revelation. WikiLeak’s attempts to make the fact that the CIA was involved in this activity a topic of debate will be difficult simply because this is not surprising, nor is it news.

The fact that an insider leaked this information is more of an issue, as is the possibility of it being another example of a foreign state using WikiLeaks to undermine and discredit the US secret services.

US intelligence officials have declined to comment on the disclosure by WikiLeaks, in all probability because they would need to analyse what information has actually been posted and assess the resulting damage it may have caused. ![]()

- David Glance is director of the UWA Centre for Software Practice, University of Western Australia

- This article was originally published on The Conversation