Eskom’s new board of directors and executive team should embrace the electric car as one long-term solution to the challenge of falling demand that is the most fundamental obstacle the state utility grapples with as it struggles to remain a going concern.

In the next five to 10 years, electric vehicles (EVs) have the potential to grow electricity demand and provide a new source of revenue and profit for the beleaguered company. Reduced demand from the mining and industrial sectors, partly as a result of the steep increases in the price of electricity over the last decade, has seen the national power producer face declining unit sales and an increase in excess capacity. As many parts of the world stride ahead in the adoption of electric cars, we ask the question, how quickly can they be adopted here?

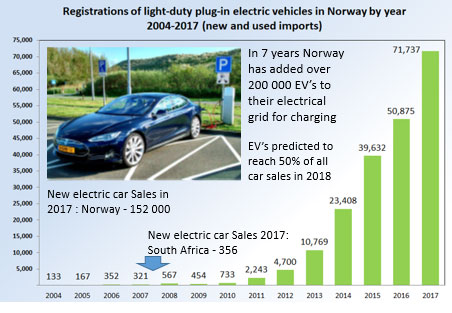

The above graph demonstrates how quickly vehicle sales can be adopted when given an enabling environment by government. Between 2004 and 2017 (a period of 13 years), EV sales in Norway grew at a compound annual growth rate of 62%. By 2017, EV’s market share grew to 21% of all new cars sold in 2017. (When combined with the sale of hybrid cars, powered by electricity and petrol or diesel, the market share rose to almost 50% of new car sales in 2017.)

By contrast, South Africa’s EV sales in 2017 accounted for just 356 of 368 000 passenger vehicle sales — not even 0.1%. The local market is roughly double the size of the Norwegian market. The cumulative number of EVs sold in Norway over the last seven years amounts to 200 000 vehicles, all of which need regular charging. The growth in sales was driven by improvements in electric cars and focused incentives from government to encourage individuals to switch over from petrol/diesel cars to EVs. A similar growth pattern can be seen in EV sales in the US, Japan and the Netherlands.

On the supply side, investment and innovation by EV manufacturers has addressed three key areas of customer concern of the early adopters, namely choice of exciting cars, total cost of ownership and driving range.

South African standards allow for two chargers.

Direct current (DC) fast-charging stations are an option for setting up commercial facilities. Estimated costs per unit come in at approximately R350 000 and current can be drawn at a rate of 75A. These stations have the capacity to charge a Nissan Leaf battery in just 25 minutes.

The cheaper, alternating current (AC) charging stations can draw 8A, 16A or 32A and will charge a Nissan Leaf in eight hours if set at 16A. To drive the roll-out of the different parties, it will be crucial that the private sector and government get involved to roll out as many chargers as possible.

Adoption of EVs by the public will see the addition of the largest energy-consuming “white appliance” ever known to man, driving up the home energy bill by 40-100%. The beauty of this for Eskom is that the current target market at are grid-connected customers, who pay their monthly accounts loyally.

If the taxi industry gets involved, along with other light commercial vehicle (van/truck) users, then these energy consumption and sales numbers will most likely double or treble. International companies are working hard at finding the right vehicles for these markets, as travel figures of 5 000-8 000km/month significantly improve the economics of owning these vehicles.

R3bn/year

Now one has to ask: should Eskom ignore potential sales of over R3bn/year? Let us consider some basic numbers: what difference could a fleet of EVs make to Eskom over time?

Drawing off the Norwegian case study, and assuming within seven to 19 years South Africa could have around 200 000 passenger EVs on the road, electrical energy consumption can be calculated, drawing from the experience of a Nissan Leaf. For example, assume the owner drives 2 000km/month, and has an electricity consumption figure of 21.25kWh/100km plus a marginal 15% for charging losses. Eskom would need to provide around 1 159GWh of electricity per year to keep a fleet of 200 000 Nissan Leafs running. At an electricity price of R1.25/kWh, Eskom together with the municipalities could see potential electricity sales of R1.5bn/year in this market at current prices.

But what should really pique Eskom’s interest is that recharging a passenger vehicle can be done during off-peak periods. For the average user that parks the EV in a garage or carport overnight, Eskom could incentivise users to charge the car between 10pm and 5am, during a period where demand for electricity is typically at its lowest. This would allow the utility to work its assets more efficiently and flatten the demand profile which exists at traditional peak periods.

Not only is Eskom currently producing excess power, it is already paid for as part of the operating model for coal-fired power stations, as the costs for Eskom are sunk — they have built the power stations already.

Fortunately, EV charging technology can now incorporate prepaid electricity, and implement time-of-use tariffs. EV charging stations can be installed with software that can be used to help Eskom shape customer behaviour in order to promote EV charging in off-peak periods.

But it gets better. Customers will not only buy their power from Eskom in off-peak periods, but they will self-fund the batteries used in their cars, and their private charging stations. EV manufacturers like Tesla envisage that in the future, EVs will form part of the home energy system allowing consumers to adjust their grid consumption energy patterns. On the back of these sales, municipalities will see a growth in their incomes from electricity distribution.

Government needs to get involved, and roll out the necessary legislation to incentivise the growth of this market. Along with the incentives, there needs to be significant capital investment into the roll-out of a charge station infrastructure for EVs, something that would be commercially feasible for many private operators.

So what is the catch, you may ask. Simply put: time. Eskom needs to capitalise on this market, grow sales and keep electricity costs down and attractive, or it will lose this entire paying customer base. Solar power companies are lining up to supply these consumers with electricity, who with their EVs and battery systems can move off the grid and not have to purchase power generated by Eskom. This is why the off-peak tariff needs to at least match or be lower than the supplied cost of a consumer installing renewable energy at their homes and thereby moving off-grid.

The combined impact of EVs and their demand for electricity, deserve the attention of Eskom and government as they are a big part of the answer to growing sales and using the surplus electricity currently available in the national grid. But the time to act is now. — Written by David Steven Knight and Warren Thompson

- David Steven Knight is a senior management consultant with over 25 years’ experience in the business and engineering management environment. He previously served as Eskom’s chief project quality engineer for three-and-a-half years

- This piece was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission