In 1972, Henry Kissinger paved the way for the normalisation of US-China relations. The US national security adviser engineered a meeting between President Richard Nixon and chairman Mao Zedong — a masterstroke of realpolitik. It peeled China away from the Soviet bloc, giving the US an edge in the Cold War.

In 1972, Henry Kissinger paved the way for the normalisation of US-China relations. The US national security adviser engineered a meeting between President Richard Nixon and chairman Mao Zedong — a masterstroke of realpolitik. It peeled China away from the Soviet bloc, giving the US an edge in the Cold War.

More recently, President Donald Trump started a trade war against China and called Covid-19 the “kung flu”. President Joe Biden stuck with Trump’s tariffs and amplified them with sanctions on Chinese tech companies, confirming Beijing’s view that the US was attempting to block the economic rise of its rival.

In February 2022, days before Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine, President Xi Jinping and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, took a step that should be no surprise to the US. They declared a strategic partnership with “no limits”. The parallel is striking: Kissinger’s realpolitik drove a wedge between Beijing and Moscow. With Trump and Biden pivoting to unvarnished hostility, the alliance of US Cold War foes has been renewed.

For the US and its allies, China’s grabby mercantilism and authoritarian excesses demand a reply. Its “made in China” policy is a state-sponsored attempt to seize control of the technologies of the future. Hundreds of thousands – perhaps more than a million — Uyghurs have been imprisoned in Xinjiang. Everyone from Norway, home to the Nobel panel that awarded the peace prize to a Chinese dissident, to Australia, which called for an inquiry into Covid’s origins, has found itself on the wrong end of Beijing’s economic sanctions.

The question for the US is what shape the response should take.

US policy towards China has evolved under its last three presidents. Barack Obama began a cautious pivot, still aiming at cooperation but taking a sterner stance on issues such as protecting intellectual property. Under Trump the shift from friend to foe was decisive, but the policy follow-through was — to put it generously — haphazard. Under Biden the animus remains, but the strategy is refined: targeted measures, coordination with allies and investment in boosting competitiveness at home.

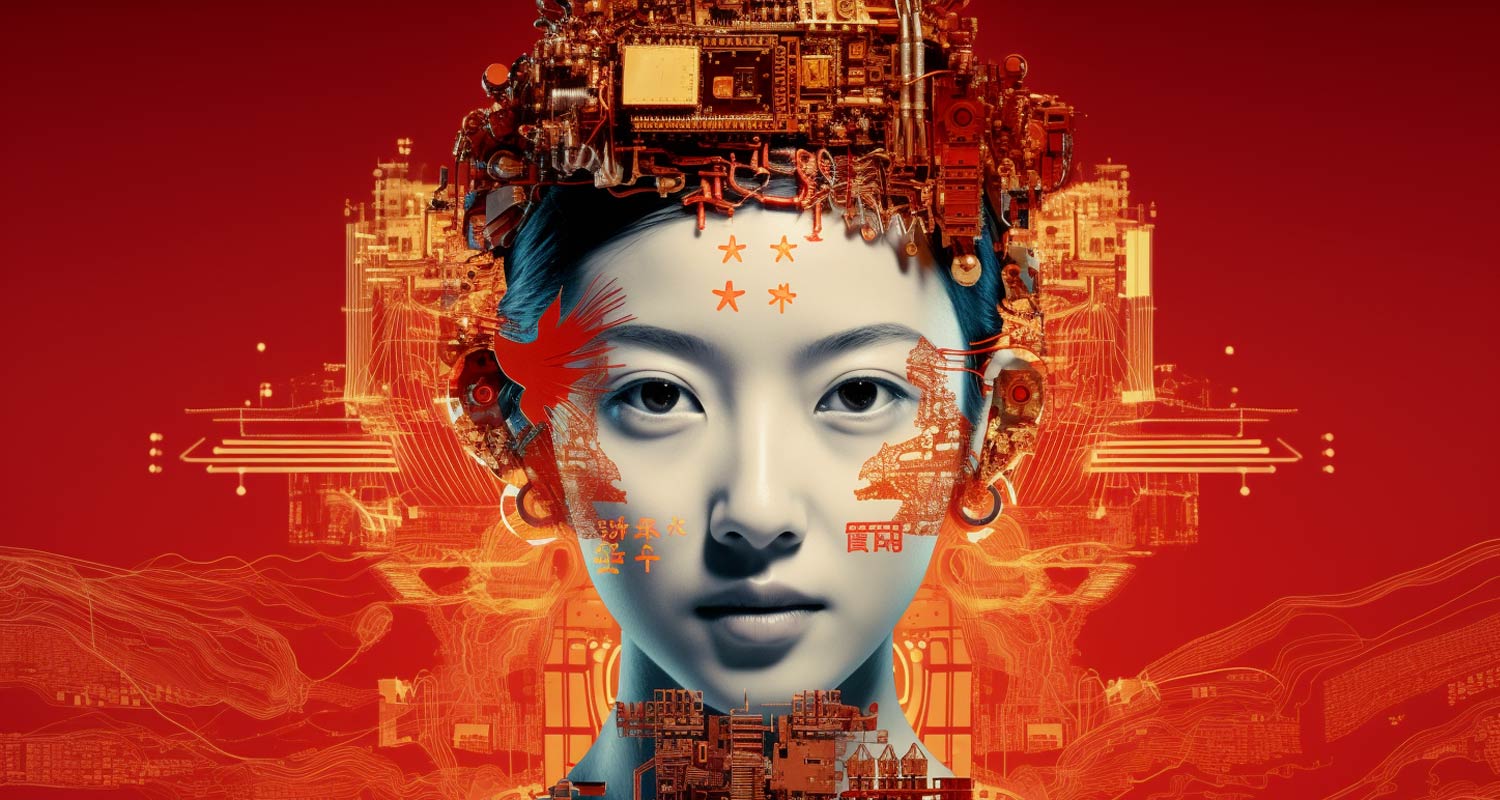

Angry red mist

Still, the US continues to view China through an angry red mist, operating under a set of misconceptions that makes it harder to get policy right. Perhaps that’s why Kissinger, recently celebrating his 100th birthday and still in action, meeting with Xi in July, said the world’s two great powers stand “at the top of a precipice”, with conflict over Taiwan “probable”.

Here are the three big things the US gets wrong on China…

Firstly, while many outcomes are possible, China is neither about to collapse nor about to take over the world. True, there are serious structural problems. Real estate and industry are overbuilt. Paying for that excess meant China took on a lot of debt. A shrinking population and fracturing relations with the US complete China’s set of similarities with Japan at the end of its own economic miracle in 1989.

At the same time, Japan didn’t stop growing until its average income converged with that of the US. China’s GDP per capita is just a quarter of the US level, and if there’s one thing the country’s policymakers are demonstrably good at, it’s planning a path up the ladder from low to high income.

In its base case, China will steady its 2023 slump and institute enough economic reform to sustain roughly 4% annual growth to the end of the decade. In that scenario it would overtake the US as the world’s largest economy in the early 2030s but never gain a substantial lead. In a more pessimistic take, China’s growth slows to 2% and never surpasses that of the US.

Either way, for the foreseeable future, the US and China will be peers and competitors.

That means the US will have to recalibrate its China policy for the long term. Trying to get an edge by demanding concessions at China’s moments of economic weakness — as Trump did during the trade war — isn’t going to work. Short-term moves that give China an excuse to change the facts on the ground to its advantage — such as then-US house speaker Nancy Pelosi’s August 2022 trip to Taiwan — aren’t a good idea either.

That means the US will have to recalibrate its China policy for the long term. Trying to get an edge by demanding concessions at China’s moments of economic weakness — as Trump did during the trade war — isn’t going to work. Short-term moves that give China an excuse to change the facts on the ground to its advantage — such as then-US house speaker Nancy Pelosi’s August 2022 trip to Taiwan — aren’t a good idea either.

Secondly, the US sees an increase in repression in recent years that demands a response. The reality is that there’s more continuity than change in China’s social controls, and China views shifts in the US position as cynically self-serving.

From Hong Kong to Xinjiang, examples of draconian controls aren’t hard to find. China’s leaders, though, recall that the US and its allies have in the past ignored authoritarian excess when it’s been in their strategic interest or forgotten about it when it was in their economic interest.

Nixon’s trip to China came at the height of the Cultural Revolution — a period of violent turmoil when children were turned against parents and students against teachers. Trade sanctions following the crackdown on student protesters in Tiananmen Square faded into the background as the US negotiated China’s entry to the World Trade Organisation. The response to repression in Tibet got quieter and quieter.

Framing the relationship as an existential struggle between democracy and authoritarianism, as the Biden administration does, is not constructive. That’s partly because a Manichean divide is impossible to bridge. Start negotiations from the position that you’re Luke Skywalker facing off against Darth Vader and the outcome is more likely to be a severed hand than agreement on reducing carbon emissions.

Framing the relationship as an existential struggle between democracy and authoritarianism is not constructive

It also leaves the US open to the charge of hypocrisy when it does deals with other non-democratic regimes. And it doesn’t play well with other countries in the region that share US concerns but are hardly democracies when measured by Western standards.

The challenge for the US: frame a China policy that’s aligned with its values but doesn’t come at the expense of broader strategic objectives such as combating climate change or stripping Moscow of support. That means more consistent policies and disciplined rhetoric than currently in evidence.

Thirdly, China’s rapid economic rise hasn’t been achieved primarily, or even to a significant degree, by cheating the US.

The main drivers of China’s economic miracle are clear: a billion-strong population provides an abundant workforce and the ability to achieve massive economies of scale. A late start on development means lots of easy wins just by absorbing technologies in widespread use in more advanced economies. China’s policymakers have also played their hand well. For example, they’ve coaxed US companies to share intellectual property as a condition for market access.

China’s huge market and its world-class infrastructure represent a powerful lure for US executives, whose shareholders demand quarterly earnings growth. CEOs, their bonuses tied to share prices, had a strong incentive to give priority to the short-term returns from China over the long-term cost of losing control of intellectual property. And the idled US workers as production moved to China? They barely registered as an afterthought.

Did China game the system, violating principles of openness and reciprocity by demanding intellectual property in return for market entry? Absolutely. Did it break the rules? In most cases, no. Foreign companies may have struck a raw deal, but no one forced them to make it.

Did China game the system, violating principles of openness and reciprocity by demanding intellectual property in return for market entry? Absolutely. Did it break the rules? In most cases, no. Foreign companies may have struck a raw deal, but no one forced them to make it.

One frequent US complaint is that China is manipulating currency exchange rates to its advantage. Policymakers said that China undervalued the yuan, which made its products cheaper for the US. But in 2001, when China entered the WTO, its wages were just 3% of the level in the US. The cheap yuan didn’t hurt, but fundamentally lower wages and quality infrastructure — not manipulation of the exchange rate — drove China’s surge in exports.

The same holds true for intellectual property theft. US policymakers estimate that this theft could amount to as much as $600-billion/year. If correct, even that sum is just 3% of China’s $18-trillion economy.

The lesson here for the US: China’s misbehaviour demands a proportionate response, but more focus should be on shifting incentives and strengthening competitiveness at home. The bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Chips and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act are a significant downpayment on achieving that objective.

On its own, though, even investment won’t be enough. The US must shift corporate incentives so they’re more aligned with the national interest, focus more on the long term and take workers as well as shareholders into account.

Few would swap the US democratic system, with independent courts and a free press, for China’s single-party state. But the attempts to overturn the 2020 election, the flirtation with defaulting on US debt and other mishaps have hardly been advertisements for the superiority of American institutions.

The upside of self-strengthening, as China has demonstrated over the past 40 years, is enormous. It’s just hard to do. There’s no time like the present to make a start. — (c) 2023 Bloomberg LP