Silicon Valley is as much about creating legends as it is about changing reality. Where else could a guy get turned down for a job and then, five years later, sell his company to the people that turned him down for US$19bn?

Silicon Valley is as much about creating legends as it is about changing reality. Where else could a guy get turned down for a job and then, five years later, sell his company to the people that turned him down for US$19bn?

I’m talking, of course, about Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp, the mobile messaging platform that is now used by nearly half a billion people around the world (72% of them use it every day). One of the reasons for the frenzy of headlines around the sale — apart from the astronomical price — is that most Americans have never even heard of the company.

This fact speaks to one of WhatsApp’s most powerful selling points: it is strong in markets where Facebook is not. Throughout Latin America, Europe and Africa, WhatsApp is either the biggest or the second biggest player — often reaching 90% of the mobile messaging market in those countries. The only significant non-US markets in which it does not dominate are those in East Asia, where homegrown players such as WeChat (China), Line (Japan) and Kakao Talk (South Korea) hold sway.

WhatsApp is dominant because it made a simple but prescient choice early on: to focus outside of America. Right from the start, the company pursued markets and demographics that are usually not favoured by the Silicon Valley elite. They built a messaging system aimed at people using phones that barely qualify as “smart” in countries where data coverage is patchy at best. When everyone else was abandoning the Nokia and BlackBerry ships, WhatsApp was signing up users by the million.

This cross-platform compatibility was always much less of an issue in WhatsApp’s home market. Text messages have been essentially free on most US phone networks for nearly a decade already, which negates one of WhatsApp’s most powerful attractions: dirt cheap messaging between networks. But in markets like our own, where a single SMS can cost as much as 200 WhatsApp messages, it has flourished.

Why would Facebook want yet another messaging app, and one that is so publicly and vehemently against all forms of advertising? And why would it pay so very much for that app? Its reasons can be grouped into two categories: the defensive and the aggressive.

First, the defensive. When you’re as big as Facebook, then anyone who takes the planet’s limited supply of attention away from your platform is a rival. WhatsApp might seem like just a clever replacement for SMS, but it’s really a private social network used by hundreds of millions of people for sharing photos, videos and audio, and for maintaining friendships. If that isn’t competitive to Facebook, then nothing is.

And because WhatsApp was designed as a mobile platform from the ground up, it has been able to ride the wave of smartphone adoption that is sweeping across the planet. In 2008, there were fewer than 150m smartphone users on earth; today there are 1,5bn and by 2017 there will be 2,5bn.

In the past four years, Facebook has successfully retrofitted its Web platform to mobile phones, but WhatsApp’s mobile DNA makes it difficult to beat. As a generalist platform, Facebook can feel cluttered as it strives to cater to billions of users. Whatsapp, by contrast, is stripped down and simple, and without any of the privacy concerns that have dogged Facebook of late.

On top of this, Google is rumoured to have been courting WhatsApp aggressively and was allegedly willing to pay even more than $19bn to secure the company. In terms of defensive strategies, not allowing an arch rival such as Google to buy WhatsApp is about as obvious as you can get.

The aggressive part of Facebook’s acquisition strategy is somewhat less obvious. Because WhatsApp has sworn off all forms of advertising, the only revenue it currently makes is from the $1 yearly fee that some users are asked to pay after their first year of usage.

I say “some” because most users report never having been charged despite using the system for years. Analysis of app stores suggests the company made just $20m in 2013.

But that $20m was more than enough to pay its 55 staff, its technology costs and make a tidy profit. The company has just 32 engineers, meaning that each one of them supports 14m users. Were the company to begin charging a bit more uniformly, it would quickly become one of the most profitable firms in the world. And that’s before accounting for the one million new users it adds each day.

So, instead of being a drawback for Facebook, this direct revenue model is actually an incredible opportunity. It represents a bulwark against the often fickle advertising market. And WhatsApp has not even scratched the surface of direct revenue generators. Simple and popular virtual goods like premium backgrounds or icons could earn billions per year without interrupting user experience one bit.

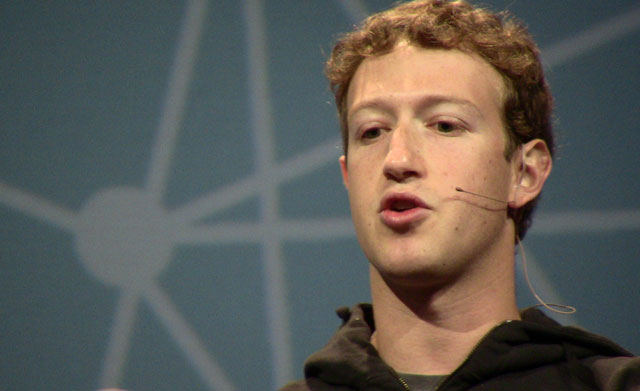

But is WhatsApp actually worth $19bn? That’s a much more difficult call to make. In five years, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg may look like a fool, or he may look like a genius. The world of social networking can be incredibly brutal. Just look at the previously dominant companies Facebook left crushed in its own wake. And that’s before you factor in the disruption the world’s mobile phone networks could cause to the company if they put their collective minds to it. The platform cost them $32,5bn in lost SMS revenue last year alone, after all.

But to Brian Acton, the WhatsApp co-founder who got passed over by both Facebook and Twitter in 2009, these concerns are largely irrelevant. Since $16bn of the sale price is in Facebook stock, he now owns around 1,5% of a company currently worth $175bn. His co-founder, Jan Koum, owns 3,25%. When they signed the deal with Facebook, they did so at the building where Koum (a Ukrainian immigrant) once stood in line to collect food stamps. As legends go, that’s a fairly memorable one. — (c) 2014 Mail & Guardian

- Alistair Fairweather is chief technology officer at the Mail & Guardian

- Visit the Mail & Guardian Online, the smart news source