In 1086, William the Conqueror completed a comprehensive survey of England and Wales. The Domesday Book, as it came to be called, contained details of 13 418 places and 112 boroughs — and is still available for public inspection at the National Archives in London. Not so the original version of a new survey that was commissioned for the 900th anniversary of The Domesday Book. It was recorded on special 12-inch laser discs. Their format is now obsolete.

In 1086, William the Conqueror completed a comprehensive survey of England and Wales. The Domesday Book, as it came to be called, contained details of 13 418 places and 112 boroughs — and is still available for public inspection at the National Archives in London. Not so the original version of a new survey that was commissioned for the 900th anniversary of The Domesday Book. It was recorded on special 12-inch laser discs. Their format is now obsolete.

The digital era brought with it the promise of indefinite memory. Increased computing power and disk space combined with decreasing costs were supposed to make anything born digital possible to store for ever. But digital data often has a surprisingly short life. “If we’re not careful, we will know more about the beginning of the 20th century than the beginning of the 21st century,” says Adam Farquhar, who is in charge the British Library’s digital-preservation efforts.

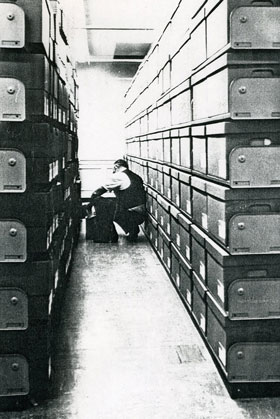

The most obvious problems for digital archivists have to do with hardware, but they are also the easiest to fix. Many archives replace their data-storage systems every three to five years to guard against obsolescence and decay. This is not as expensive as it sounds: hard drives are cheap and reliable. The threat of hardware failure is overcome by keeping copies in different places. The British Library has storage sites in London, Yorkshire, Wales and Scotland.

Collecting digital material is trickier, particularly online. Archivists can only harvest those parts of the web that are freely accessible. Anything requiring user inputs — passwords, searches, forms — is off-limits. Streaming media, such as online videos, are hard to capture.

Changes in software and file formats create more hurdles. “Many of the digital objects we create can only be rendered by the software that created them,” says Vint Cerf, a pioneer of the Internet who now works for Google. If the original program has gone, an archive of mint-condition files can be useless. By the time software is more than a decade old, running it usually requires hardware emulation — essentially fooling programs into thinking that they are running on old hardware.

Although technical problems can usually be solved, regulatory obstacles are harder to overcome. Laws force copyright libraries, such as the Library of Congress, to seek permission before archiving a website. Regulation can be even more damaging when it comes to preserving such things as computer programs, games, music and books. These often come with digital-rights management (DRM) software to protect them against piracy. Archivists who want to circumvent such programs can find themselves on the wrong side of the law. America’s Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) makes such circumvention a criminal offence.

Copyright and DRM will loom even larger as the nature of information systems evolves. The original Internet was by default an open environment, making copying easy. The mobile world, with its widely popular smartphone apps, is much less so. As companies more fiercely protect their wares, contemporary digital artefacts run the risk of never being archived. Libraries have no mandate to collect apps, such as Angry Birds or Instagram, which form part of popular culture.

Despite all these difficulties, the world’s libraries have tried for over a decade to conserve some aspects of their national digital heritage. America’s Library of Congress started its digital-preservation programme in 2000 with US$100m from the government. Its Web archive currently stands at around 10 000 sites, many of them owned by the American government, and therefore exempt from copyright. Privately run sites are more difficult to include. For some archiving projects, only a fifth of webmasters reply to e-mails seeking permission for a copy.

Digital pack rats

Following the Library of Congress, most national libraries in rich countries now have some sort of digital-archiving programme. In Britain, for instance, the National Archives keeps copies of all government websites. The British Library is archiving all British online material.

Yet the best-known digital preservation effort is the Internet Archive, a private non-profit effort. Its servers are home to the Wayback Machine, a popular Web service that lets users see how a website looked on specified dates in the past. Founded by Brewster Kahle in 1996, Internet Archive collects, stores and provides access to billions of Web pages as well as other digital media such as books, video and software. The collection stands at roughly 160bn web pages. It operates on the principle that it is better to seek forgiveness than to ask for permission.

More recently, geeks have rushed in where official agencies fear to tread. They have always been pack rats. Today they gather on websites such as Tosec (short for “The Old School Emulation Centre”) to collect old software. But these collections have their own limitations. They focus heavily on games and operating systems; people tend not to have the same nostalgia for early versions of spreadsheet applications as they do for Super Mario Bros. More important, the material is very much under copyright.

Despite the proliferation of archives, digital preservation is patchy at best. Until the law catches up with technology, digital history will have to be written in drips and drabs rather than the great gushes promised by the digital age. — (c) 2012 The Economist![]()

- Image: Cushing Library/Flickr