At a recent public lecture, held at the University of Johannesburg, I was inspired by the impact that the Bloodhound SSC project has had on science, mathematics and engineering in schools around the world.

At a recent public lecture, held at the University of Johannesburg, I was inspired by the impact that the Bloodhound SSC project has had on science, mathematics and engineering in schools around the world.

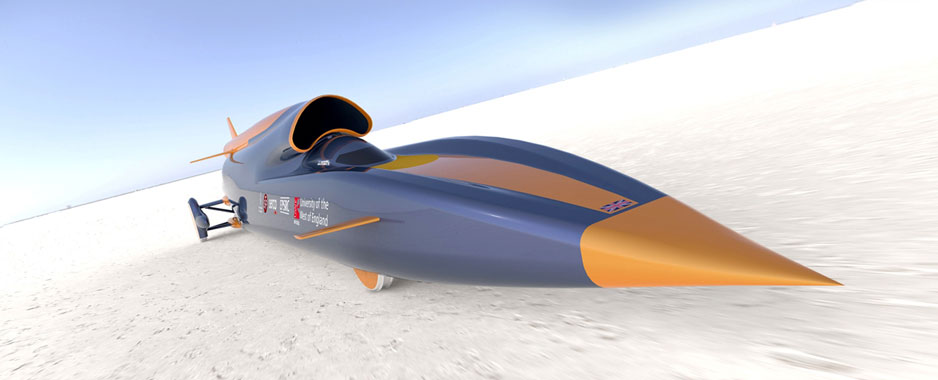

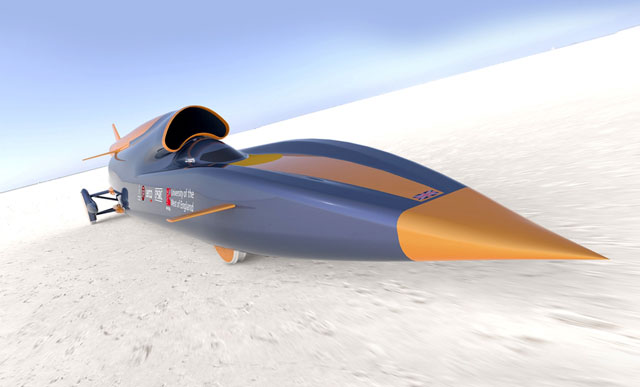

The project, whose aim is to set a new world land speed record at supersonic speed — the SSC stands for supersonic car — has made its raw data available to educators and enthusiasts to dissect and explore.

The amount of data that the project is sharing is vast and includes research, design, build and testing of the Bloodhound SSC vehicle. This is a big deal.

It’s rare for this level of data being made available for educational or research purposes. In Formula 1 racing, for example, this type of information is kept secret as it’s crucial as each team tries to squeeze every bit of performance from their vehicles within the very tight confines of Formula 1 regulations. Even much of the scientific and engineering data collected by space agency Nasa is classified.

So, why is Bloodhound’s decision a big deal? Worldwide, there is a shortage of scientists and engineers, a problem that needs to be addressed from a young age. The situation in South Africa is even more acute. According to the South African Agency for Science and Technology Advancement, about 50% of South Africa’s scientific output today is produced by scientists over the age of 50. Twenty-five years ago, this figure was 18%. The solution, the agency says, is to expose learners from a young age to career opportunities in science, engineering and technology. There is also a need for them to be exposed to appropriate role models in those fields.

Bloodhound has four people working on its South African education programme, and has already signed up 426 schools across South Africa, 102 of which are situated in the Northern Cape, where the record attempt will take place at Hakskeenpan outside Upington.

Bloodhound SSC project director (and former world land speed record holder) Richard Noble says the project offers a great opportunity to provide students with access to real design challenges and test data as the it develops.

The Bloodhound team is trying to smash the world land speed record by propelling a manned vehicle up to a speed of a thousand miles an hour (1 609km/h), or about 374km/h faster than the speed of sound.

At full speed, the Bloodhound SSC will cover a distance of 1,6km in just 3,6 seconds — that is the distance of four-and-a-half soccer pitches every second!

The specially designed, 13m-long supersonic car will weigh 7 786kg and will be fitted with a Rolls-Royce EJ200 jet from a Eurofighter Typhoon, a cluster of Nammo (Nordic Ammunition Company) hybrid rockets and a 650bhp racecar engine that drives the rocket oxidiser pump.

The power produced will equal that of about 180 Formula 1 race cars and deliver a total of 135 000bhp. Let that sink in for a moment: the Bloodhound SSC will take off at a speed faster than a bullet being fired from a Magnum 357.

If you are wondering how the Bloodhound SSC will come to a stop, the driver, Andy Green (a fighter pilot in the Royal Air Force), will experience six Gs (g-force) when he slams on the brakes. That’s six times the force of the Earth’s gravity.

After a global search for a prime location to execute the attempt, the team discovered Hakskeenpan — view it in Google Earth — in the desolate Northern Cape. Mier, the local municipality, is one of the most sparsely populated in South Africa and is the poorest per capita. There is a population of about 7 000 people, with unemployment running at about 65%.

The Bloodhound SSC project will lead to the communities in this area receiving a much needed infrastructure boost and the fast-tracking of their 20-year wait for decent water supply infrastructure.

It’s still two years until the Bloodhound SSC’s attempt to get into the record books, but the impact the project is already having on future scientists and engineers in South Africa is inspirational. — © 2014 NewsCentral Media

- Regardt van der Berg is senior journalist at TechCentral. Find him on Twitter