Virtual reality start-ups are accusing Facebook of using a familiar playbook to muscle out rivals in what could be the digital platform of the future — prompting a new line of scrutiny from competition enforcers.

Facebook is the world’s biggest virtual reality hardware maker thanks to its 2014 acquisition of Oculus for US$2-billion. Its practices are now drawing the attention of the US justice department’s antitrust division, which is talking to developers about their interactions with the company, according to two people familiar with the matter.

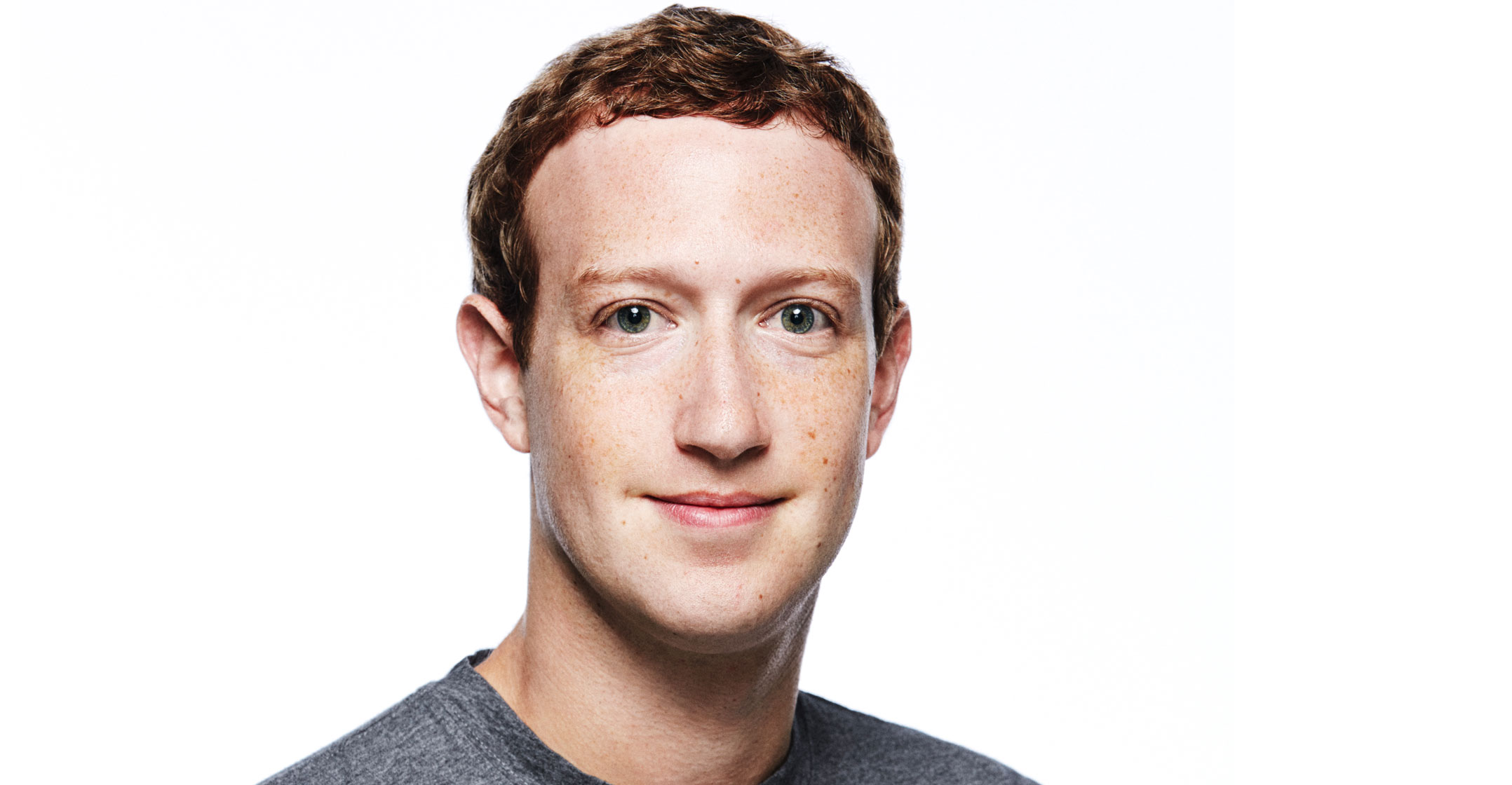

The scrutiny over Facebook’s virtual reality business reflects broader concerns that the social media pioneer has grown too powerful. One US lawmaker, during a hearing with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, attributed the company’s dominance to a simple strategy: Copy, acquire and kill any company that’s a competitive threat.

Software developers and start-up founders say the world’s biggest social media company is now using that same playbook to undermine competition in the virtual reality market.

Facebook’s Oculus acquisition was a bet by Zuckerberg that virtual reality would go beyond gaming to encompass a broad array of experiences and eventually change the way people work and communicate, experts say.

Facebook is pushing hard to establish its presence in virtual reality because it represents a unique opportunity for the social media player to establish itself as the leader in the next state-of-the-art platform to deliver products and services to its users without relying on Google or Apple.

Antitrust

The Federal Trade Commission is preparing to bring an antitrust case against Facebook as soon as next week. But that investigation has been focused mostly on whether the company’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp harmed competition.

The social media giant last year disclosed an investigation by the justice department, but neither the company nor the department has provided details or explained how the inquiry is different from the FTC probe. The FTC declined to comment. The justice department didn’t respond to a request seeking comment.

Developers say Facebook is using its market power to thwart companies that offer competing games and services. It’s copying the most promising ideas, using below-cost pricing for its devices and making it harder for some apps to work properly on the platform, according to developers and a hardware maker.

Faceboook declined to comment about the complaints.

Facebook has a 39% share of the virtual reality hardware market, making it the industry’s largest player, according to data from market intelligence firm International Data Corp. Smaller players include Lenovo Group, Sony and HTC, while Apple is developing its own mixed virtual and augmented reality headset for launch as early as 2022. Facebook launched its latest headset, the Quest 2, in October, cutting the price to $299 from $399.

Facebook has a 39% share of the virtual reality hardware market, making it the industry’s largest player, according to data from market intelligence firm International Data Corp. Smaller players include Lenovo Group, Sony and HTC, while Apple is developing its own mixed virtual and augmented reality headset for launch as early as 2022. Facebook launched its latest headset, the Quest 2, in October, cutting the price to $299 from $399.

At the core of the complaints is the way Facebook runs the platform and competes against software developers who build apps and depend on the platform for their business.

“Our industry is getting eaten alive by Facebook,” said Cix Liv, who co-founded startup Yur, which makes technology that can be integrated into Oculus games to track fitness metrics. “Any application that has a chance of being mildly competitive with them, they have to kill it somehow.”

Yur released its fitness tracking app for Oculus in September 2019 and spent months working to satisfy Facebook’s security, privacy and performance benchmarks to get the app into the Oculus app store. While the app was available to users on another marketplace, Liv said, Yur couldn’t get it into the Oculus store even though he said the start-up met Facebook’s requirements.

Facebook in the (northern hemisphere) spring released a software update for Oculus that prevented Yur’s technology from working within games, according to Liv. Liv said Yur was the only company that experienced such an issue. Subsequent updates required users to delete the Yur app in order to get the Oculus headset working again.

Then in September, Facebook released its own fitness tracker called Oculus Move that Liv said has the same functionality and look as Yur’s product. He accuses Facebook of effectively killing his product by keeping it out of the store and breaking its functionality, all while working to copy his technology.

‘Control the future’

The reason is simple, Liv says: Facebook wants to favour its own products on the platform so it can collect as much data about users as possible in order to “control the future of ads by knowing more about you than any company in history”.

Virtual reality consultant Nima Zeighami said Facebook “locked down the ecosystem so much that if someone makes an app that competes with them too much, they can just blacklist them”.

Liv said he was forced out of his company after speaking out against Facebook on Twitter about a month ago. He said the venture capital fund backing his start-up, Venture Reality Fund, told him that he would have to leave the company if he continued criticising Facebook. Liv said he believed the fund sought to pacify Facebook because of its potential to acquire the fitness app and other start-ups the fund is backing. One of the fund’s partners, Tipatat Chennavasin, denied telling Liv that he had to leave the company if he kept criticising Facebook.

The criticisms against Facebook echo those levelled against other tech giants, such as Amazon.com, which sells its own branded products in competition with third-party sellers on its marketplace. Apple also owns the App Store, where its products compete against those of developers who depend on the store to sell their apps.

The criticisms against Facebook echo those levelled against other tech giants, such as Amazon.com, which sells its own branded products in competition with third-party sellers on its marketplace. Apple also owns the App Store, where its products compete against those of developers who depend on the store to sell their apps.

In October, Democrats on the US house antitrust panel recommended that congress prohibit a dominant platform from competing against companies that operate on the platform — in essence, to break them up.

Other app developers have similar stories of copied products and functionality issues regarding Facebook. One is Guy Godin, a developer who created Virtual Desktop, which allows users to replicate their computer desktops on the Oculus headset. It was released on Oculus in 2016 and has become a top seller on the platform, he said.

In June 2019, Godin introduced a version that could stream games and other content to the Oculus headset, a feature that was popular with gamers because they weren’t tethered to their computers with a cable, Godin said.

A few weeks later, Facebook told him to remove the feature or else his app would be pulled from the Oculus store. Facebook explained it was due to poor user experience and health and safety issues. Godin called those claims “totally bogus” but said he had no choice but to comply because he depends on Oculus for 90% of his revenue.

In September that year, Facebook announced it was releasing a competing product called Oculus Link, which allowed users to stream content but required a cabled connection to the user’s computer.

Happy to compete

Godin said he’s happy to compete against Facebook’s product but that it isn’t a level playing field because the company controls what features he can offer.

“They just want to own it all,” he said. “If there’s only one company, it’s going to be very hard to survive as a developer.”

The complaints mirror allegations about Facebook raised in the findings of the house investigation of tech platforms.

“Facebook is a case study, in my opinion, in monopoly power because your company harvests and monetises our data, and then your company uses that data to spy on competitors and to copy, acquire and kill rivals,” representative Pramila Jayapal, a Washington Democrat, told Zuckerberg when he testified in July.

A group of more than 40 developers organised in September and considered writing an open letter to Facebook calling for more transparency to its Oculus store policies and other changes to benefit developers, according to Liv. He said they’re now looking to team up with an established organisation that can represent their views similar to the way Apple’s App Store developers created the Coalition for App Fairness.

A group of more than 40 developers organised in September and considered writing an open letter to Facebook calling for more transparency to its Oculus store policies and other changes to benefit developers, according to Liv. He said they’re now looking to team up with an established organisation that can represent their views similar to the way Apple’s App Store developers created the Coalition for App Fairness.

To help secure its position in the market, Facebook is selling the Oculus headset at a loss, according to Stan Larroque, the founder and CEO of Lynx, a Paris start-up that promotes its virtual reality headset to businesses. Engineers at Lynx, whose headset uses many of the same components as Oculus’s Quest headset, estimate that Facebook sells the latest version of the headset, the Quest 2, at a $50 loss per device, said Larroque. That makes it impossible for smaller device makers to compete, he said.

“The message is we’re Facebook and we don’t care if we make money or not, but we’ll flood the market and virtual reality will be Facebook Reality pretty soon,” Larroque said.

The house report warned that below-cost pricing, also known as predatory pricing, is a risk in digital markets because they tend to be characterised by a winner-take-all dynamic, where one or two companies end up dominating. As a result, there’s an incentive to pursue growth over profit by engaging in predatory pricing for some period to force out competitors.

Developers also complain that Facebook squeezes them by forcing them to pay a commission on sales, a complaint also leveled at Apple. One of them is Darshan Shankar, the founder and CEO of Bigscreen, which lets users stream movies on the Oculus headset and interact virtually with friends as they watch together.

Rental fee

When a user rents a movie on Bigscreen, they have to use the Oculus in-app purchase system, which collects 30% of the rental fee. That ultimately makes the economics of the business unworkable for the start-up, he said. Shankar said Facebook refuses to negotiate on the 30% commission that Bigscreen has to pay.

“It’s literally impossible for anyone to start an e-commerce or media business in VR because these walled gardens are gatekeepers,” he said. “Entire industries are impossible because of them.” — Reported by David McLaughlin, (c) 2020 Bloomberg LP