Information used to be a localised affair. Before the Internet, bank accounts were confined to physical ledgers in a filing cabinet and took so much work to copy that they rarely left the building.

Information used to be a localised affair. Before the Internet, bank accounts were confined to physical ledgers in a filing cabinet and took so much work to copy that they rarely left the building.

IBM mainframes entered the office in the 1960s and 1970s and introduced the era of digital centralisation. It wasn’t a conscious shift as much as a convenient one. Computers were good at managing information, so we kept giving them more. Bank cheques, bond coupons and stock certificates soon disappeared in favour of electronic record keeping. Today it would be unthinkable to rely on a paper bearer instrument of significant value.

Digital databases enabled features that would otherwise be unwieldy: fraud detection, credit scores, targeted advertising. But it placed a responsibility on the data collectors as well. As a central source of information, they inevitably become arbiters of human interactions.

Historically, powerful entities tend to consolidate their power. But the recent populist backlash might push technologists to move in the opposite direction.

Humans originally lived in small communities where social capital was paramount and trust was granted accordingly. It wasn’t that long ago that people conducted all their banking at a single branch office and bank staff knew customers by name. This led to the sort of personal relationships we see in old movies such as It’s a Wonderful Life.

Such relationships may feel comfortable, but they don’t accommodate the size and scale of modern societies. As civilisation evolved, institutions arose to enforce rules and lower the risk of cooperating with strangers. Instead of trusting each of our counter-parties, we need only trust the institutions. Now we can trade trillions of dollars in assets in the financial markets every day without worrying whether a stock certificate might be a forgery.

Consensus

We don’t outsource trust in all aspects of life. A lot of laws aren’t strictly followed or enforced. Instead we rely on communities to come to a consensus regarding socially acceptable behaviour.

Even if the government wanted to regulate private behaviour, it couldn’t station a police officer in every home to follow our every move.

Except, increasingly it can. Today, people are unlikely to pay cash for their office betting pools. More likely they’re using Venmo, where payments are automatically screened for suspicious activity. Anything that appears illegal, even transactions between friends, results in a locked account.

Digital panopticons enable stricter enforcement of rules than previously seemed possible (and maybe were ever thought desirable). Money laundering was criminalised in the US in the 1930s, but it wasn’t until the Bank Secrecy Act of 1970 that financial institutions were required to actively police it. Back when customer records lived in filing cabinets, it was infeasible to monitor every transaction for suspicious activity.

Digital panopticons enable stricter enforcement of rules than previously seemed possible (and maybe were ever thought desirable). Money laundering was criminalised in the US in the 1930s, but it wasn’t until the Bank Secrecy Act of 1970 that financial institutions were required to actively police it. Back when customer records lived in filing cabinets, it was infeasible to monitor every transaction for suspicious activity.

Once it was established that a financial services provider could be found liable for a customer’s source of funds, its responsibilities rapidly expanded. Today, not only do banks need to comply with know your customer (KYC) laws, they’re also expected to know your customer’s customer (KYCC). The idea of currency — money that belongs to its current holder — is gone, replaced by the notion that the provenance of every asset must be traced. Even gold bars can be burdened by their history.

Regulatory outsourcing isn’t limited to banks. Any company with an Internet-connected database can be deputised for law enforcement. Facebook and Google respond to tens of thousands of government data requests each year. Amazon.com has been ordered to turn over Echo recordings from its smart home speakers. Large tech companies even provide handy Web portals through which law enforcement agencies can request records.

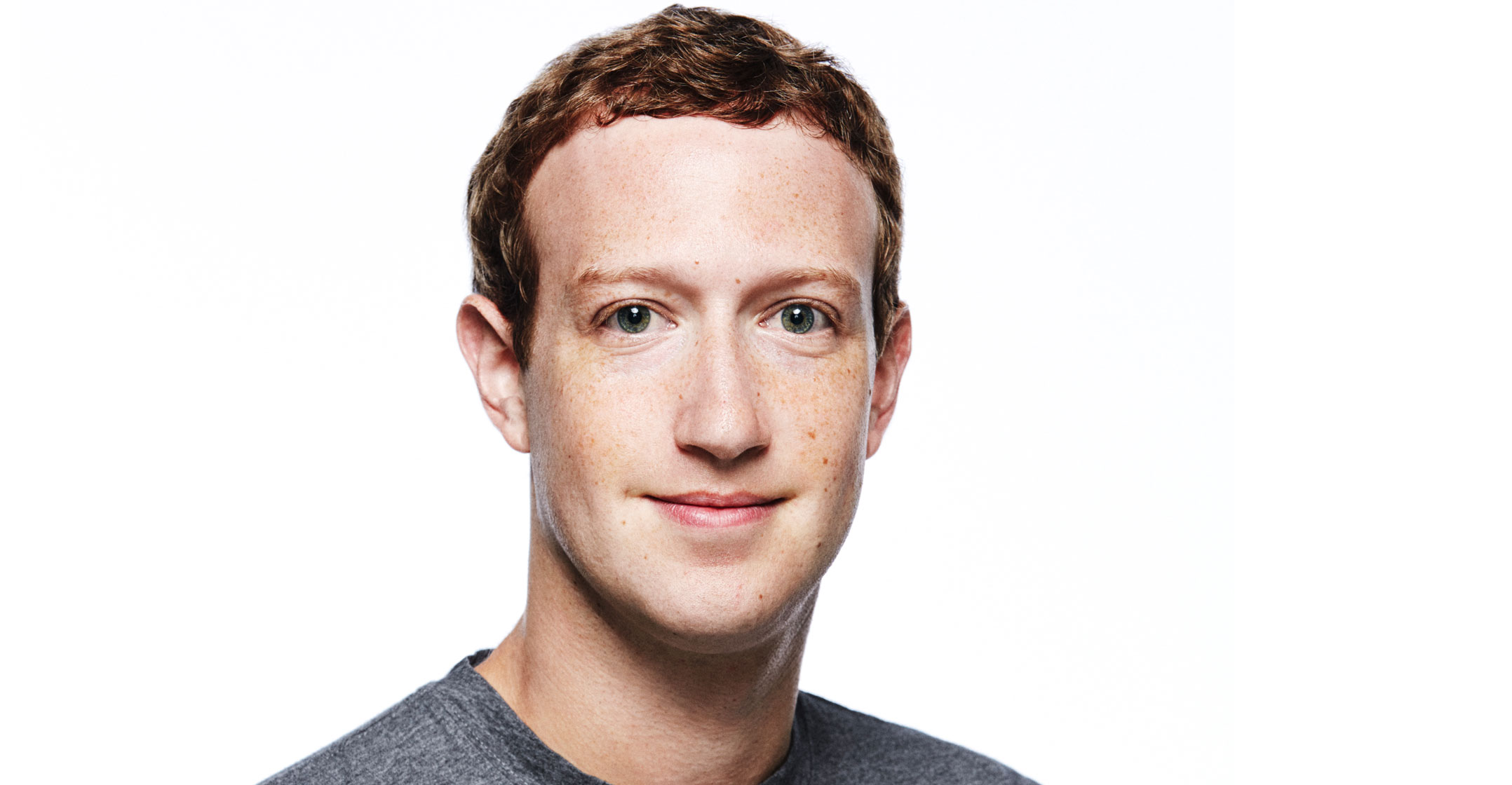

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg made the most compelling case against breaking up his company at the Aspen Ideas Festival in June, when he pointed out the potential loss of an ally in helping regulators address problems like election interference and misinformation campaigns: “Breaking up these companies wouldn’t make any of these companies better… You would have those issues, you’d just be much less equipped to deal with them.”

Facebook keeps intimate information on more than two billion people in one convenient location. Why would the government break that up?

There’s a conflict here. Technology that was created to promote cooperation between strangers is now being used to control them.

Increasingly global

As businesses become increasingly global, they’re torn between a need to comply with US laws and a desire to avoid alienating their own customers. After Edward Snowden’s disclosures of tech companies’ complicity in National Security Agency surveillance, foreign customers fled US tech providers in favour of overseas competitors. More recently, workplace productivity app creator Slack Technologies came under fire for blocking users in Iran, Cuba and other countries sanctioned by the US. Microsoft-owned GitHub followed with similar actions soon after.

That tension is creating demand for technology design choices that won’t permit companies to police their customers. Facebook enabled end-to-end encryption for its Messenger app, and Apple built its iPhones in such a way that even Apple can’t hack into them. When Open Whisper Systems received a subpoena requesting user information for its encrypted messaging app Signal, it was only able to supply the duration of a user’s membership. The company retained no other information about its users.

Tech companies are also starting to use a double-blind information-sharing technique known as homomorphic encryption to collect and analyse data. They get the benefits of massive data mining without the responsibility for monitoring it. Proposed applications for this technology range from medical records to voting software. Double-blind computation used to be prohibitively expensive, but technological advances have made it feasible for large-scale analysis. Instead of a reassuring motto like Google’s “Don’t Be Evil”, systems can now be designed to preclude evil.

The cyberpunk movement in the early 1990s foresaw the lawlessness of cyberspace. It proposed technological solutions to facilitate cooperative behaviour in the absence of a governing body. The goal was anarchy — not in the sense of chaos, but in the sense that no one would be in charge. Instead of relying on regulators and police, user-defined rules would be enforced with economic incentives and software.

Bitcoin is the most prominent example. It’s a bearer instrument, but instead of a certificate, cryptographic signatures are used to authorise unforgeable transactions. Ledger history is stored in a database replicated across tens of thousands of machines around the world, and users are expected to verify transactions for themselves.

In a world where confidence in the establishment has fallen to an all-time low, “Don’t trust us” is an attractive sales pitch. When Facebook announced libra, the company was careful to emphasise its limited authority over the proposed cryptocurrency. Libra will be managed by a Swiss foundation of which Facebook is only one member.

The company didn’t fool anyone with those decentralisation claims, but the goals are instructive. Facebook knows that the best way to win over users is to minimise its own involvement.

Even central banks can appreciate this. At this year’s Economic Policy Symposium in Wyoming’s Jackson Hole, Bank of England governor Mark Carney suggested a synthetic hegemonic currency that could be provided through a network of central bank digital currencies.

It’s a distinct break from half a century of dollar dominance. US treasuries make up about two-thirds of global reserve holdings, all residing as database entries at Federal Reserve Banks, where every transaction can be monitored or stopped.

Reluctant

Other countries don’t share Americans’ appreciation for US regulatory authority, especially those at the receiving end of sanctions.

European Union member states are reluctant to sacrifice trade and investment opportunities with Russia, Iran and other economies by adhering to US sanctions. As a solution, European banks set up a special-purpose vehicle called the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges, or Instex, to help companies do business with Iran without actually sending money across borders. Instex acts as a clearinghouse that matches credits and debits for trade, but transactions get netted and batched so that money doesn’t cross Iranian borders. It hasn’t been put to much use so far, but an informal version has existed for centuries. Hawala is an international value-transfer system that relies on a global network of brokers. It may look primitive because of the absence of contracts and courts, but hawala scales remittances to poor countries that international banks find too risky to serve. Hawala brokers don’t comply with KYC requirements — not in the legal sense, anyway. Participants know each other based on informal relationships in local communities.

A crypto version exists as well. Bitcoin lightning is a decentralised clearing system where participants send bitcoin payment messages all around the world. Earlier this year, a series of lightning payments took place between users in the US and Europe, then to Iran, then Israel, concluding with a donation to a humanitarian aid programme in Venezuela. The payments were privately cleared through the lightning protocol, and if participants hadn’t announced their game on Twitter, no one would have known.

A crypto version exists as well. Bitcoin lightning is a decentralised clearing system where participants send bitcoin payment messages all around the world. Earlier this year, a series of lightning payments took place between users in the US and Europe, then to Iran, then Israel, concluding with a donation to a humanitarian aid programme in Venezuela. The payments were privately cleared through the lightning protocol, and if participants hadn’t announced their game on Twitter, no one would have known.

Trust takes a long time to create but only a moment to destroy. When people lose confidence in the institutions that serve them, economic activity breaks down. The solution isn’t to make powerful institutions even more powerful but to create technology that reduces the need to trust powerful institutions.

The greatest innovations leverage human instinct to expand what’s possible. Financial institutions talk a lot about banking the unbanked, but that might do the unbanked a disservice. A monolithic panopticon is no substitute for local knowledge.

This all sounds bad if you’re in charge of US foreign policy or any type of regulation. It’s good if you want a world where people can cooperate without interference. After all, that’s how economic progress is made. — By Elaine Ou, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP