Outside Sweden, Daniel Ek isn’t a household name. That will probably change this year when the 33-year-old seeks to turn Spotify, the music streaming business he founded a decade ago in Stockholm, into a publicly traded company that could be worth US$8bn.

The success of the initial public offering will hinge on whether investors believe Ek can turn rapid revenue growth into sustainable profit at some point in the not-so-distant future. The soft-spoken, shaven-headed Swede must overcome concerns that Spotify is a mere distribution channel, beholden to the big three music labels whose pricey licensing fees are a serious constraint.

He also needs to convince the market that Spotify won’t wither under competition with wealthy rivals like Apple and Amazon.com, which happily subsidise music services to sell more stuff.

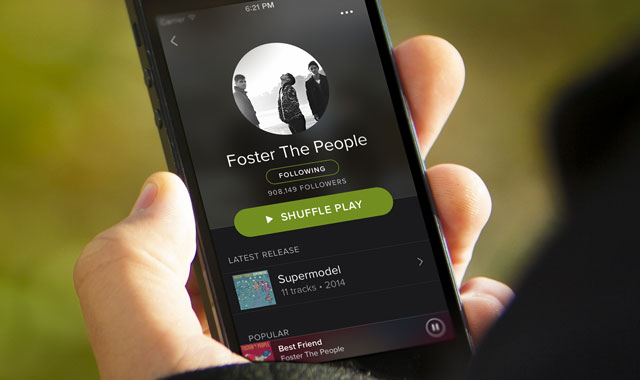

So far, Ek has managed the challenges well. Spotify’s business model is based on selling $10/month subscriptions, although it does have a free service on which it sells advertising. He’s become adept at delicate negotiations with music labels that would’ve put off someone less determined. Ek has also overcome early errors in the shift to mobile and ensured that Apple’s streaming service didn’t derail growth.

Along the way, he’s realised, too, that running a company with more than 1 500 employees often means doing boring stuff that doesn’t come naturally. Wearing a black t-shirt emblazoned with the slogan Suits Suck, Ek recently told a tech conference audience that he’d learned to love human resources and good enterprise software.

Spotify does have a few crowd-pleasers for its IPO: a popular brand, strong revenue growth and more than 40m paid subscribers (double the number at Apple). Sales rose almost 80% to almost €2bn in 2015, according to accounts published in Luxembourg. They’re expected to have risen another 50% in 2016, according to a July Bloomberg News report.

It’s still making losses, though. Spotify’s biggest weakness is paying out most of its revenue to labels and publishers for the right to play their music. Its cost of revenue has hovered between 81% and 83% in the past three years mostly because of those royalties. That means its gross margin of 17-19% is miles below the norm for a zippy tech company and more akin to an old-school retailer.

Spotify fans say it can be profitable once the subscriber base is big enough to absorb the royalties and other expenses such as R&D and marketing. But reaching profit will need big improvements, some of which are not totally in Ek’s control such as maintaining pricing power. Either Spotify cuts licensing costs by wrangling better terms from the labels or it will have to spend less on other things.

By way of comparison, Netflix — the most successful subscription-based digital content business in terms of its 92m customers — is on course to have brought in $8,8bn of revenue and $348m in operating profit in 2016, according to Bloomberg data. It has a 32% gross margin, earns $108/year per user in the US and $97 overseas.

For Spotify to get to $300m in operating profit, it will need to increase its paid subscriber base to 60m, lift the gross margin to 30% and boost average revenue per user to $100 annually from about $72 last year. So, still a lot of work to do.

And if Netflix-like valuations are driving Ek, he has a long way to go. Netflix trades at about 5x forward revenue. A similar multiple would imply a $15bn valuation for Spotify’s IPO. That seems about as likely as a reconciliation tour between pop music’s arch-enemies Kanye West and Taylor Swift.

Ek has people rooting for him, though. The future of the music business may hang on Spotify. It already brings in some 10% of all revenue for the labels, and is large enough to help offset the power of the tech giants. That’s a lot of weight on Ek’s young shoulders. — (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP