On Wednesday last week, Facebook’s share price closed at an all-time high of US$217.50/share. By the close of trading the next day, however, it had fallen to $174.97.

This almost 19% drop was the biggest one-day loss in US market history in terms of the value it represented. Overall, $119-billion was wiped out of Facebook’s market capitalisation. That is more than the GDP of Morocco.

Investors were prompted into selling not just because the company’s revenue and user growth came in slightly below expectations, but because Facebook projected these growth rates to decline even further.

When a company is trading on multiples that demand sustained high growth, this kind of revelation can cause a significant de-rating, and that is exactly what happened. Yet, even after the correction, Facebook is still trading on a price-to-earnings multiple of over 24 times (down from over 33). Its price-to-sales ratio is over 10.

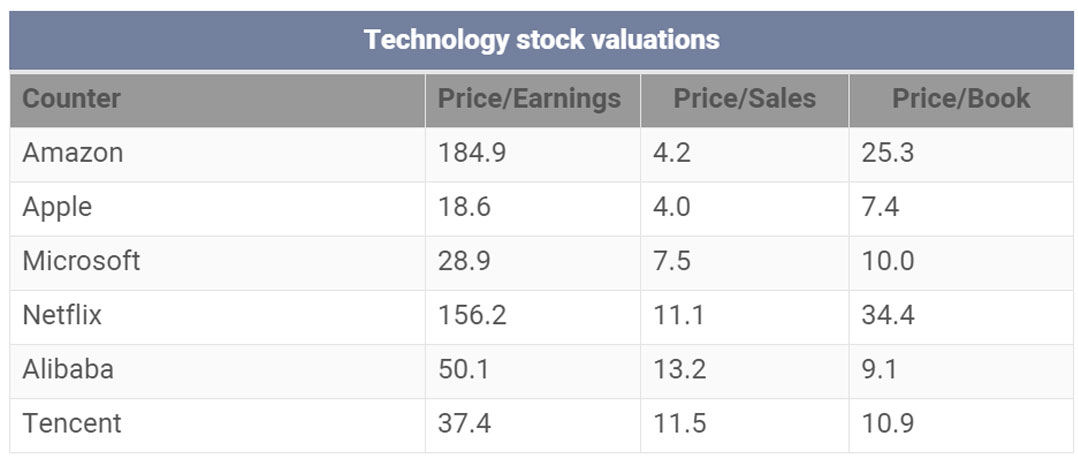

In other words, the share is still priced for growth. As the below table indicates, its well-known peers are also trading on high valuations:

There is a lot of debate in the investment industry about whether these kinds of valuations are sustainable. Many will point to what happened to Facebook last week as exactly the risk that investors face in these companies: they only have to disappoint the market marginally for their share prices to be punished. Yet, even taking into account last week’s events, the Fang+ Index on the New York Stock Exchange has still outperformed the S&P 500 by 28% over the past year.

The argument many will make is that the technology giants in particular, and the industry more broadly, are riding a wave that isn’t slowing. Kevin Williams from Bataleur Capital says that technology is a secular growth story that investors can’t ignore.

“If you look at the revenue growth in the technology space, it grows at multiples above global GDP growth,” he points out. “We think the valuations in the technology space in general are reasonable given the growth outlook, although obviously there are certain exceptions.”

Williams notes that there are now 3.6 billion Internet users, which is more than half of the world’s population. In total, 30% of the people on the planet use social media. This is also growing at 7%/year, which is twice the global GDP growth rate.

The companies taking advantage of this growth in areas such as e-commerce, Internet advertising, online payments, video streaming and cloud services are therefore highly attractive. In particular, those that have been able to leverage existing client bases to spread their footprint into other markets have a significant advantage.

“Facebook has over two billion users,” Williams points out. “That’s more than a quarter of the world’s population. Google also has two billion users, on Android phones. These are phenomenal client bases that these companies have, and they are unmatched by anyone else globally.”

This has resulted in an environment where big players just keep getting bigger.

“The prize for being number one is enormous, because how often do you think about the second or third or fourth online shopping or classified advertising business?” says Rory Spangenberg, director of global equities at Northstar Asset Management. “From an investment perspective, that’s also very interesting because you don’t want to necessarily be in the second or third competitor.”

Winners keep on winning

Due to their focus on continued development, the biggest players are also able to entrench their positions.

“Many of these companies are very strong cash generators, and they spend an enormous amount of money on R&D and new projects to discover the next big thing, which just entrenches their moat,” Williams points out.

The strength of their core business also allows them to put up with losses in other areas for extended periods if they have high enough convictions about future profitability. Tencent has been particularly adept at this in the Chinese market. It started with only an instant messaging service, but has spread into fields as diverse as streaming, cloud computing and gaming, and has become a dominant player almost everywhere it turns.

“The strength of Tencent is that diversity,” Spangenberg says. “The early success and the scale that it reached so quickly in the core social media and instant messaging businesses allowed it essentially to incubate the other business because it could stomach huge losses.”

A characteristic of these companies has been their exceptional return on invested capital. Spangenberg notes that a McKinsey study on corporate value creation has picked up a clear trend in this regard.

“Over the long run, companies have delivered a return on invested capital of about 10%,” he says. “Since 2013, however, there has been a step change in the median return because IT and health-care companies have come to represent a much larger part of the market. In traditional industries you haven’t seen any change in the long-run average return, but there is a small group of sectors where you have seen a meaningful step change.”

According to technology bulls, this is good reason to believe that although Facebook’s short-term decline is noteworthy, it doesn’t change the long-term story.

“The technology space is volatile because it’s such a fast-growing area,” says Williams. “And because valuations of these companies in absolute terms are not cheap, there can be a lot of price movement in the underlying shares from time to time. But that doesn’t change the secular growth structure of this industry.”

- This article was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission