[By Dominic Cull] A flurry of initiatives aimed at achieving a reduction in mobile termination rates will provide interesting sideshows, but beneath the politics of the moment, the real action remains an intimate dance between the Independent Communications Authority of SA (Icasa) and the mobile networks.

The initial mobile termination rate, also known as interconnection rate, of 20c/minute was set between Vodacom and MTN on 8 August 1994. This was amended on 28 May 1999, shortly after it was announced by government that a third mobile cellular telecommunications licence would be issued.

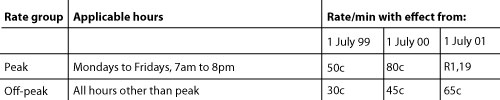

Vodacom and MTN issued a joint notification to the SA Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (Icasa’s precursor) that they had decided on the following phased increase in the rate:

A final increase to the current rate was implemented by Vodacom and MTN on 1 November 2001. Cell C launched on 17 November 2001 and had to accept this rate.

Eight years later, the parliamentary portfolio committee on communications will hold public hearings on the rates after issuing a proposal that would see rates reduced to 60c/minute from 1 November 2009.

At a recent briefing session the committee expressed a view that there had been “tacit collusion” between the operators and that “phenomenal increases” in termination rates had led to “exorbitant profits” and acted to the particular detriment of poor and marginalised communities.

Given this level of rhetoric, the appearance of executives of the mobile networks at the hearings in October promises to be compelling viewing.

The department of communications has also told parliament that regulating mobile termination rates is essential in order to achieve competitive pricing and that this is one of its priority action items. It has stated that it will consider issuing policy directions to Icasa to achieve this.

Meanwhile, the embattled regulator has launched an initiative which it terms “moral suasion” as a way of trying to effect a short-term reduction in the rates. This process is in practise nothing more than Icasa asking the operators to go and renegotiate the rates on a bilateral basis — which is how interconnection rates are set under the Electronic Communications Act — and then to report on their progress to a multilateral forum.

Though I have my own thoughts regarding the somewhat speculative nature of appeals to the morality of mobile network operators, it is interesting that Icasa has made it clear that it knows the cost of termination and will not accept any proposal from the operators which is out of line with this figure.

While both initiatives should be welcomed in that they at the very least raise consumer awareness, they share a common lack of legislative or regulatory authority. Any reduction in mobile termination rates flowing from these processes will be essentially a voluntary — or rather “voluntary” — act by the operators and as such a product not of method but of compromise.

The regulatory process to be followed by Icasa under the Electronic Communications Act before it can set interconnection pricing remains the most important avenue for reducing the rates. And it is here that all the problems are to be found.

In assessing Icasa’s performance to date in dealing with mobile termination rates, the parliamentary portfolio committee, in the particularly pugnacious form of Adv Johnny de Lange MP, offered a brutal analysis of Icasa as vertebrally challenged and incapable of making decisions. Icasa, he said, should be neither a friend of nor prisoner to industry.

Accurate this may be, but it could also be argued that government’s apparent disinterest in having a strong communications regulator has played a major part in the current ineffectiveness of Icasa.

Process is a problem for the regulator — it has been tripped up by procedurally on a number of issues over the past two years and is perceived by industry to be vulnerable to legal threats. Icasa admits that it is litigation-averse, a sense no doubt heightened by the anticipated receipt of Vodacom’s bill for legal fees flowing from the suicidal urgent interdict to prevent the operator’s listing earlier this year.

It seems that Icasa is unwilling to accept the opinion of Gilbert Marcus SC to the effect that it can pursue a simplified approach based on a benchmarking exercise. It has received its own legal advice — together, no doubt, with that offered by others — which points to a lengthier process. This is not necessarily a bad thing but the exact process to be employed is not yet clear.

It is a sure thing that mobile termination rates will come down. The best-case scenario is probably a significant initial “voluntary” reduction effected within six months followed by a regulatory pricing regime finalised within a year.

A word of caution: the political will which spawned the current initiatives to reduce the rates also present a significant threat. There is a danger that a vulnerable Icasa will, in seeking to finalise the required process in the shortest possible time due to political pressure, compromise its process.

While this may not be challenged in the context of termination rates, it is highly likely to prejudice other critical interventions such as local-loop unbundling and, perhaps, the application of a use-it-or-lose-it policy to the assignment of spectrum.

What is the cost of mobile call termination? In response to a question from the portfolio committee, Icasa stated that it “had done its own analysis of costs and has found that the cost is not more than 40c”.

The “not more than” in this statement speaks to a worrying lack of precision, but the regulator has at least come up with reasonably accurate figure which is less than the rate paid from 1999 onwards. The answer probably lies between this and ResearchICT Africa’s suggested 25c, but a reduction to 40c would make an excellent start.

So we know the answer. We just don’t know how to get there.

- Dominic Cull specialises in electronic communications regulation. Find him online at www.ellipsis.co.za. This column is written in his personal capacity