Imagine the horror. Waves of denial, smashing against the rocks of inevitability. Your brand new, US$9 000 radio controlled aeroplane has just flown over that far clump of trees, heading for the horizon, making its break for freedom. Before its fuel runs out and it smashes itself into $9 000 worth of smithereens.

Imagine the horror. Waves of denial, smashing against the rocks of inevitability. Your brand new, US$9 000 radio controlled aeroplane has just flown over that far clump of trees, heading for the horizon, making its break for freedom. Before its fuel runs out and it smashes itself into $9 000 worth of smithereens.

This is one of the fundamental problems with radio. It’s a shared medium. If you make radio waves, anyone in the right place with the right kit can pick them up. Or, anyone in the right place with the right kit can stuff up yours.

You want the waves, and you want them for yourself.

Where there are some people that want what others have, you get one of two things. Politics. Or markets.

Where there is someone in control, you get politics. Where there is risk and reward, and a way to trade one for the other, you get markets.

Radio was always been regulated through the application of state power. This is why radio regulation is highly politicised, centrally controlled and manifestly inflexible.

There are exceptions to this regime – the industrial, scientific and medical (ISM) bands were carved out as “licence exempt” as far back as the late 1940s.

For the first 60 years, ISM was mostly “i” — plastic welding, microwave ovens. Then came interference-tolerant radio communications technology, namely Bluetooth and Wi-Fi. No central control, but risk and reward. Markets bloomed.

Fundamentally, this kind of interference-tolerant technology uses spectrum sensing to share the waves. If someone is using a channel, back off, and wait, or shift to another. In current Wi-Fi, it’s pretty basic for carrier sense, in 802.11ac it’s got horns on for full dynamic frequency selection.

We have now reached the place in technology, and the place in time, where spectrum sensing is cheap enough to do everywhere, and all the time. With pervasive spectrum sensing, we can let those who need to use the radio waves use them if no one else is. We can turn a fundamentally political system into a market system, one that responds to supply and demand in real time, one where you could buy and sell spectrum from other users.

What has changed? Our ability to sense, analyse and automate really, really cheaply, on a national scale.

So this brings us back to our hapless radio-controlled aeroplane owner. Most countries have set aside a few bands for model aircraft. In South Africa, it’s 35MHz (aircraft only), or the more chaotic 54, 40 and 27MHz bands. Or you can use newer frequency hopping/spread-spectrum radio in the 2,4GHz ISM band (which works brilliantly to prevent interference, but clogs up quickly with many users).

If you use reserved spectrum you’re fine, unless another radio-controlled aircraft pilot uses the same frequency as you (which is why RC clubs have a peg board system to keep tabs on who’s using what).

Ideally, as an RC aeroplane enthusiast, you check which spectrum is fairly clear, and use that. How do you check? Spectrum analysers are expensive.

Do you know what’s not expensive? Cheap Linux computer boards ($40); off-the shelf USB TV tuner dongles ($15); incredibly powerful Realtek RTL2832 software-defined radios. Oh – wait, that’s free, they come with a TV tuner dongle. Nice aluminium case ($20).

And then add a bunch of paid-for and open-source software.

Model aircraft enthusiasts are just one of a huge community of hackers making the match-head sized RTL jump through hoops. Other people are listening to transmissions from aircraft (the big ones full of people). Listening to weather balloon data. Monitoring meteor scatter. Snooping on digital voice systems. Want to give it a crack? Whet your appetite here and here.

But what if we can build a sensing device from cheap, commodity hardware? Could we solve a very real global problem that’s slowing everyone’s economies? What if we can sense everywhere, all the time?

With this as a starting point, a crack team assembled. Casting aside my “I write these articles in my personal capacity” hat and firmly pulling on my Internet Solutions one, we decided to see what could be done about solving the incredibly vexed question of “How do we allocate, assign and re-assign spectrum efficiently, in real time?”

The results so far are outstanding. It can be done. Right now. Affordably. Even in South Africa, with a plummeting rand-dollar exchange rate.

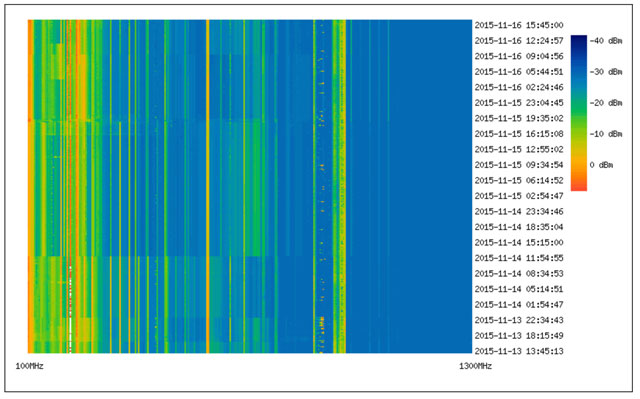

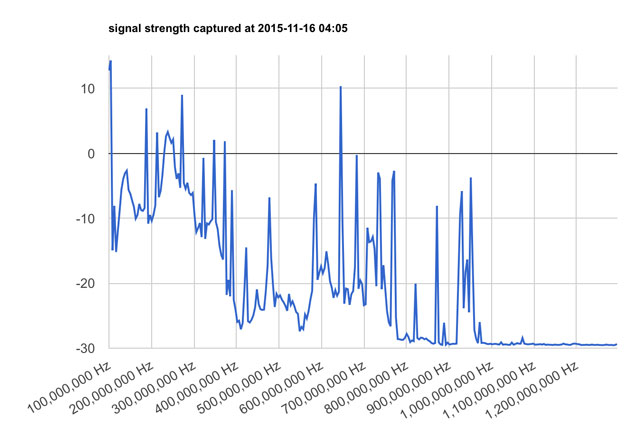

This is how it works. First, use a TV tuner as radio front-end. Its software-defined radio scans a band and spits out either raw I/Q data or field strength data, which you suck up into a cheap Linux computer running the hacked open-source drivers. From there, pump it into a witches’ brew of open-source and custom written code, which does three things for you.

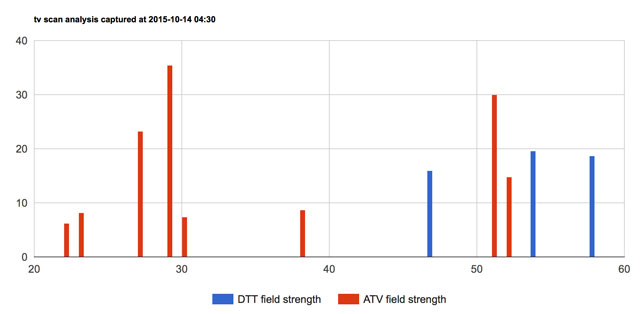

First, it does some pre-processing of data. This includes rough sweeps of occupancy of all channels, as well as some cleverness using a signal’s characteristic “fingerprint” to identify certain common transmissions, like analogue TV and digital TV. Second, it reads some key environment data points, like GPS location, device status (battery, power, temperature, storage, etc), and wraps up all this information into packages. Third, it encrypts and sends these packages either via its own cellular radio over GPRS, or an Ethernet port, to a message broker service on the Internet.

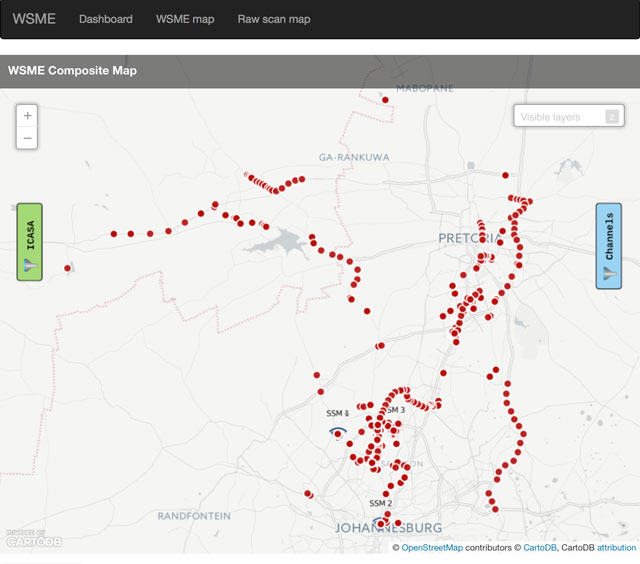

The message broker allows you to ingest millions of these packages from the Internet, and feed them securely and reliably into a back-end service we’ve dubbed the “white-space management engine”, which does visualisations, mapping and GIS layers, and runs a workflow engine to allow automated actions based on rules.

This is where the cool part begins. Now that you have hundreds or thousands of sensing devices scattered all over the country in fixed locations, or, for instance, mounted on a friendly courier company’s vehicles, you can build up a very accurate picture of what’s going on.

We’ve only built four devices so far in a proof of concept that can scan from 30MHz to 1,3GHz (they can go up to 1,7GHz with current hardware, and just add a down-converter or another USB radio front end and go higher). At R600 to R800 each (with some manufacturing economies of scale), you could blanket a country with spectrum sensing modules for a few million rand and get real-time channel occupancy data everywhere, all the time.

Considering that the communications regulator, Icasa, had a budget of close to R60m for licensing and compliance, and another R60m for engineering and technology last year, and has a total budget of R394m this coming year, this seems like a bargain.

How well does a rapidly built prototype work? Very well. Surprisingly so, on fact. The technology may be off-the-shelf consumer grade kit, but because it’s deployed in large swarms, it is allowed to be a little unreliable. If one breaks, send in another — rather like the server blades in Amazon’s data centres.

Story continues below…

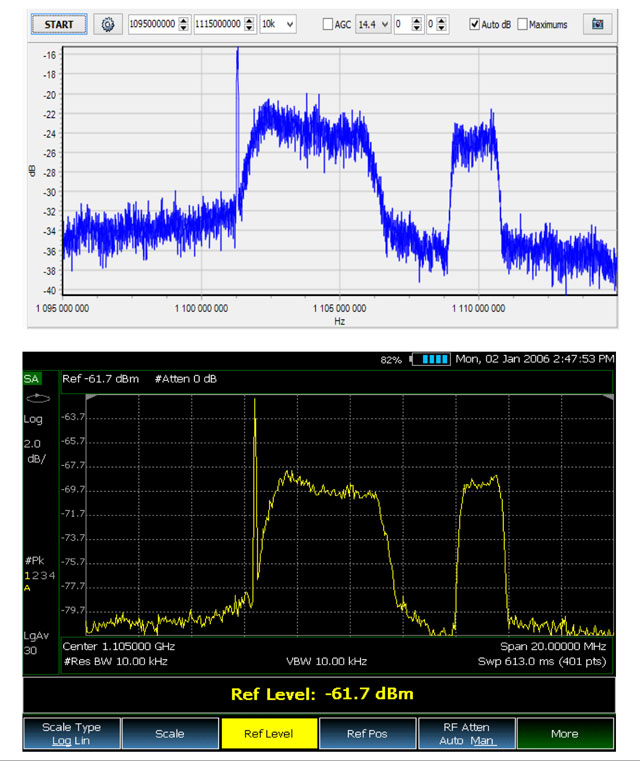

Lab tests show these spectrum sensing modules are exceptionally (or at least predictably) stable with temperature, frequency drift, sensitivity and other parameters. When compared with a professional grade Agilent spectrum analyser (FieldFox 9912A), it’s at least as sensitive with higher resolution. Low-cost spectrum sensing module? $70. FieldFox? $9 000. And you can’t run whatever code you want on that baby, or connect it to the Internet.

Spectrum sensing was always a component of cognitive radio (“thinking radio”) going back to the original work by Joseph Mitola.

Because it used to be so expensive, and so technically challenging, it fell out of favour in the cognitive radio research world, even as TV white spaces became the cool thing to trial (even in Cape Town and Polokwane.

Now it’s time for spectrum sensing to make a comeback, to join its natural sibling, the open-loop white space database built on propagation modelling. Everywhere, all-the time spectrum sensing closes the loop, completes the picture.

The technology world has moved quickly. We live in a world of the Internet of things, cloud computing, big data, the consumerisation of IT — everything provisioned for on-demand, bought “as a service”.

So, let’s do it.

Low-cost, mass-market hardware, integrated using open-source software onto a generalised computing device, all connected as an Internet of things, sending data into the cloud where it’s managed, visualised and processed, with the masses of information processed using big data tools to look for interesting patterns and make data-driven decisions via intelligent automation, to deliver spectrum management as a service.

If nothing else, this concept scores incredibly well in buzzword bingo.

- Roger Hislop is an engineer in the research and innovation group at Internet Solutions