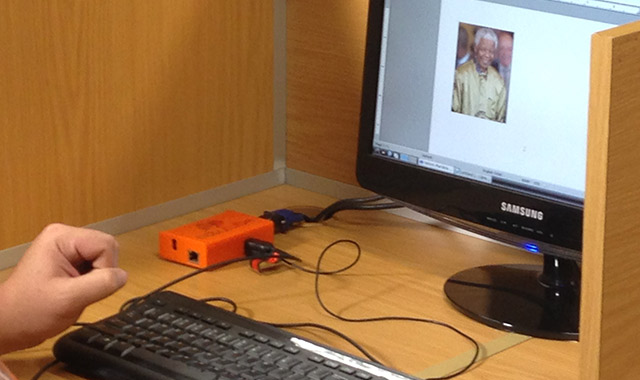

The developers of a new, small-form-factor computer aimed at South African schools hope their invention will have an impact on the quality of the country’s education.

The EduCube, developed in South Africa, is aimed at pupils all the way from grade one to matric and offers a range of educational software, past exam papers and an offline version of Wikipedia for scholars.

The machine is the brainchild of Johan Roos, 37, the founder and MD of Enterprise Intelligence, a company that specialises in small-form-factor computing aimed at industrial and enterprise-scale users.

The company sells the Ei Cube, which is similar in design to the EduCube, to industries where traditional computers do not work well due to power requirements or harsh operating conditions. It has also implemented the Ei Cube as a low-cost Asterisk communications server that is used in call centres.

The idea for the EduCube was formed two years ago and was put into reality with the help of Luyanda Vappie, EduCube co-owner and director for strategy and innovation. “In the two years since we put the idea into reality, we have been working on getting the right content for EduCube,” says Roos. “This included getting Wikipedia onto the device and sourcing past exam papers, open-source handbooks and other materials.”

Small-form-factor computers such as the Raspberry Pi and Arduino have become popular where traditional computers won’t work or are simply too large or expensive to implement.

Roos says his company could not use the Raspberry Pi as the base device on which to build the EduCube because it has a number of shortcomings. “It only uses SD cards for storage, and we need something more reliable.” Also, the Raspberry Pi requires consistent power otherwise its circuit board “burns”. Power can’t be guaranteed in rural communities where the EduCube will be rolled out.

“The USB ports on the Raspberry Pi also supply limited power and we needed more power to run a range of peripherals,” Roos says, adding that the fact that there’s no VGA port meant that an additional adapter is needed, adding to the cost.

Enterprise Intelligence instead conceptualised its own computer that conformed to the specifications they felt were needed.

The EduCube features a dual-core, 1GHz ARM processor and has 1GB of RAM. It also features 16GB of built-in Nand memory and storage can be expanded using a serial ATA connector. It also has a VGA port.

The company is working on an eight-core version, which will also have a physical hard drive to allow the company to store large video files or even host data in basic server-like environments.

The EduCube runs a custom version of Linux and is based on Ubuntu. It uses the optional Alex DE (Development Environment) to create the same look and feel as Windows. This, Roos says, was to keep the learning curve to a minimum and cut the training time needed.

The EduCube has been piloted in five primary schools in Centurion, Midrand and Johannesburg, with 20 machines deployed per school.

Roos says the solution caters to all scholars, from grade one to matric, with all the content, including 440 000 Wikipedia entries, stored on the device — meaning no Internet connection is needed. Pupils can search past exam papers for specific questions, while younger students can explore the educational games that come bundled with the EduCube.

Part of the initiative is to also get funding for the translation of the Wikipedia content loaded onto the EduCube, into the top five national languages.

The EduCube also contains a number of other educational software tools, including a Delphi-compatible cross-platform programming language called Lazarus.

The EduCube retails for R2 000, although volume discounts are available. The price excludes keyboard and mouse, but a small, notebook-like keyboard will be bundled in future.

Roos says the next step is to put pre-recorded classroom lessons on the device. “These classes can be stored on the device where no Internet connection is available, or pulled from the cloud should the school have access to broadband.” This will also help to improve teacher skills, says Roos.

Under a maintenance agreement, EduCube devices are updated with fresh content every two or three years, ensuring the latest national curriculum is covered. Schools with Internet access will soon also be able to download updates from a central server, but this feature is still in development. — © 2014 NewsCentral Media