Incensed over Apple’s decision to stop paying it billions of dollars in licensing fees for smartphone chips, Qualcomm plans to retaliate by asking a US trade agency to ban the imports of iPhones, according to a person familiar with the company’s strategy.

Qualcomm is preparing to ask the International Trade Commission to stop the iPhone, which is built in Asia, from entering the country, threatening to block Apple’s iconic product from the American market in advance of its anticipated new model this northern hemisphere autumn, according to the person, who asked not to be identified because the discussions are private.

The ITC is a quasi-judicial agency in Washington that has the power to block the import of goods into the US and processes cases more quickly than federal district courts — the venue in which the companies are accusing each other of lying, making threats and trying to create an illegal monopoly.

The escalating legal dispute revolves around patents Qualcomm holds that let it to charge a percentage of the price of every modern high-speed, data-capable smartphone, regardless of whether the devices use its chips. Apple argues the system is unfair and Qualcomm has used licensing leverage to illegally help its semiconductor unit.

That spat worsened late last month when Apple cut off technology licence payments to San Diego-based Qualcomm. The blow to the chip maker’s most profitable business spurred the company to intensify the fight to improve its negotiating position.

“They have to do something,” said Kevin Cassidy, an analyst at Stifel Nicolaus. “The bigger risk is other companies or countries say we’re not going to pay, too. That’s the danger of letting Apple get away with this.”

Spokesmen for Qualcomm and Apple declined to comment.

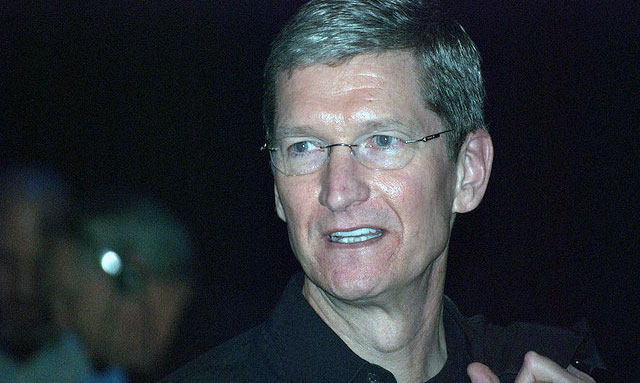

Qualcomm hasn’t offered fair terms as required under rules governing the licensing of patents, Apple CEO Tim Cook said when asked about the possibility the chip maker could try to halt iPhone sales anywhere in the world.

“That’s both the price and the business terms,” Cook said Tuesday during a conference call with analysts. “Qualcomm has not made such an offer to Apple,” he added. “I don’t believe anyone’s going to decide to enjoin the iPhone based on that. There’s plenty of case law around that subject. But we shall see.”

The iPhone is built in Asia by contract manufacturers. A successful appeal to the ITC could potentially lock it out of the US market, which accounts for 40% of Apple’s total sales. Apple generated US$86,6bn in its Americas region last year. The iPhone provides more than 60% of sales for the Cupertino, California-based company.

Qualcomm has already shown the price of its fall-out with Apple. It cut its revenue outlook this quarter by $500m citing the likelihood of not receiving licensing fees from Apple. If that carries on for the rest of the year, almost one-third of its lucrative licensing revenue, most of which is profit, will disappear.

The current iPhone uses a mixture of Intel and Qualcomm modems to connect to networks. Up until the iPhone 7, Qualcomm was the exclusive supplier of that crucial part. The company’s patents cover the fundamentals of how data and voice is encoded and transmitted between networks and phones. By stopping payment to contract manufacturers who make the iPhone — who, in turn, pay Qualcomm — Apple is interfering with contracts that predate the debut of the iPhone, Qualcomm argues.

The trade commission in Washington is the obvious choice of venue for a next round in the fight. Both companies are familiar with the agency — Qualcomm’s chips were briefly blocked from the US during a patent fight with Broadcom that it settled in 2009, one of the few legal disputes it has lost. Apple was threatened with the ban of some of its iPhones during its fight with Samsung Electronics. Nokia is pursuing a case at the agency to try to forge a new licensing agreement with Apple after the two were unable to renew a contract that was struck after an earlier patent dispute.

The ITC has the advantage of speed, judges with experience in patent law and the ability to get an import ban, said Alex Hadjis, a patent lawyer with the Oblon law firm in Alexandria, Virginia, who specialises in cases before the agency.

The rules about how patents contributed to industry standards are “a bit murkier, but the ITC may turn out positive for patent owners”, Hadjis said. There have been some agency rulings “with reasoning that can be viewed as friendly” to a patent owner like Qualcomm with standard-essential patents, he said.

Qualcomm may even go further afield, testing courts in the UK, Germany and China, said Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Matt Larson. Each is known for being faster than US courts. A UK court, in an unrelated case, in April made clear that patent owners on standardised technology can block companies unwilling to take licensees.

And in China, where Apple gets about one-fifth of its sales, Qualcomm negotiated a settlement with regulators that established what kinds of rates it can charge. It used the decision to end a royalty battle with China’s Meizu Technology in December.

Under the current circumstances, there seems little prospect of settlement.

“We strongly believe we’re in the right. And I’m sure they believe that they are,” Cook said of the dispute with Qualcomm. “And that’s what courts are for. And so we’ll let it go with that.” — (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP

- Reported with assistance from Alex Webb