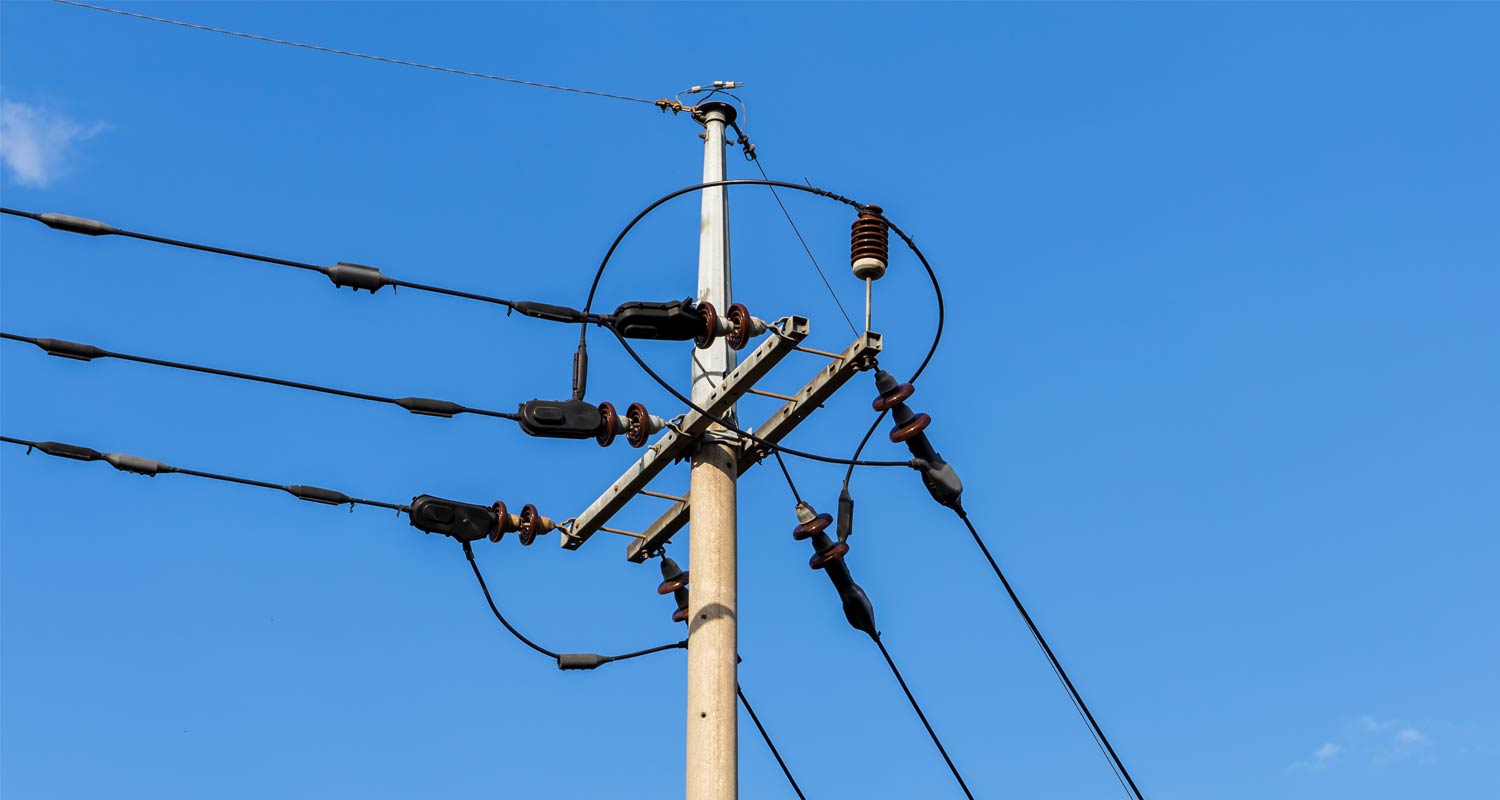

Late last year, residents of Yeoville and Bellevue — crumbling inner city areas of Johannesburg — went without power for four weeks after a 63-year-old cable broke. For several months after, power to the electricity supply was rotated between the two areas in four-hour blocks. Then the cuts were reduced to two hours a day as the city’s aging infrastructure grappled with overloading.

Late last year, residents of Yeoville and Bellevue — crumbling inner city areas of Johannesburg — went without power for four weeks after a 63-year-old cable broke. For several months after, power to the electricity supply was rotated between the two areas in four-hour blocks. Then the cuts were reduced to two hours a day as the city’s aging infrastructure grappled with overloading.

And yet, on 1 July, electricity costs for some of South Africa’s poorest people, including in Yeoville and Bellevue, went up as much as 60%.

A few hundred metres away, across one of Johannesburg’s main transport arteries, a different scene is playing out. St John’s College, one of South Africa’s most expensive schools, reduced its reliance on the grid — and cut its costs — by installing solar panels.

In the gap between Yeoville and St John’s lies a central struggle affecting the poor in South Africa’s richest city, a title it holds due the concentration of businesses and the number of millionaires. Reducing reliance on the erratic and costly electricity supply requires adopting renewable energy solutions that are themselves prohibitively expensive for most. Local utilities, meanwhile, say more home solar and batteries are contributing to strain on their coffers, forcing them to increase rates to maintain service.

“We are very adversely affected. It’s a problem,” says Tsepo Matubatuba, a 67-year-old retired priest. Last month, Matubatuba helped form the Yeoville Bellevue Electricity Movement to protest against rising costs and the neglect poorer suburbs are subjected to when power supplies break down.

Electricity prices have roughly tripled in South Africa over the past 14 years, which along with increased power cuts has prompted many rich households and businesses to spend thousands of rand each on clean energy solutions. A typical solar-and-battery setup costs about R150 000 and roughly 670MW of solar power has been added to residential rooftops nationwide, according to GoSolr, South Africa’s biggest renter of panels and batteries for homes. About half of that capacity is in Johannesburg.

Prepaid pinch

City residents with post-paid utility accounts currently fork over an electricity connection fee of about R1 150/month, plus sliding-scale costs based on actual usage. But that fee proved prohibitive for poor people. So, City Power, Johannesburg’s utility, started offering prepaid meters: no fee, and higher rates.

The prepaid option is meant to ensure that people actually pay for their electricity usage, and that City Power doesn’t have to chase customers over outstanding bills. But to the utility’s consternation, the option also caught on with the middle class — especially those using less power after installing solar and batteries. Roughly 115 000 customers that City Power considers “affluent” have moved onto prepaid meters, meaning they can skip the R1 150 monthly service charge.

Then last month, City Power increased the cost of prepaid power by 12.7% — more than double inflation — and added a R230 monthly service charge. Together those measures equate to a 60% increase in electricity costs for the poorest families, which use about 200kWh/month, according to EE Business Intelligence.

Read: Delinquent municipalities owe Eskom R82-billion

“The reality for many South African households is: pay for electricity or feed your children,” says Tracy Ledger, head of the energy transition program at Johannesburg’s Public Affairs Research Institute. “Prepaid meters have become a way of punishing people for being poor.”

City Power argues that the monthly charge is necessary to help fill a R40-billion maintenance and upgrade backlog, and similar measures have been put in place by other South African municipalities. Johannesburg has been trying to implement the charge since 2018, and earlier this year floated a plan that would have imposed a fee of more than R500/month.

But critics say the increase is the latest example of a city run by chaotic and constantly changing coalitions milking its poor. On Tuesday, Johannesburg mayor Kabelo Gwamanda quit after months of political infighting and amid persistent struggles to balance the budget. The city has had eight mayors since 2019.

South Africa does offer the poor a way to apply for free electricity. National treasury allocates money to different municipalities to supply free services based on the number of poor households in their cities. In the most recent financial year, the treasury allocated R1.8-billion to Johannesburg for more than 1.1 million indigent households’ electricity, the most of any of the country’s five biggest metropolitan areas.

“We appeal to our indigent customers to take advantage of this benefit,” says a spokesman for City Power.

It’s unclear how much of that money actually reaches low-income people. To receive the benefit, one must get onto Johannesburg’s indigent register, a process that requires an array of documents and income of less than R6 213/month. Only South African citizens or permanent residents can apply, and the application process must be repeated every six months.

Belinda Kayser-Echeozonjoku, caucus leader for the Democratic Alliance, the biggest opposition party in the city council, says the indigent register is inaccurate. She and other critics also argue the new charge was imposed without adequate consultation. A number of prepaid meter owners say they were unaware it existed until they bought power in July.

“Free basic services [in Johannesburg] have been very badly implemented,” Ledger says, adding that the money national treasury allocates can easily be channelled to general use. “Hands-down the worst offender — gold medal — is the City of Johannesburg.”

In a televised interview on Tuesday, energy minister Kgosientsho Ramokgopa emphasised that municipalities receive money to subsidise electricity for the poor. “It’s not a funding problem, it’s an execution problem,” he says.

Indigent register

City Power says it gives 50kWh of free electricity each month to just under 11 000 Johannesburg households with prepaid meters. That’s out of the 171 000 households with prepaid meters that the utility deems “non-affluent”, a number that lines up with 2022 data from Statistics South Africa. By contrast, Cape Town provides free power to 316 000 people and the City of Tshwane — which includes Pretoria — provides the service to 155 000 people, according to Statistics South Africa.

Johannesburg itself says that it covers some electricity costs for about 175 000 households through its Expanded Social Package Programme via City Power and Eskom. Eskom says it supplies 6 384 households in Johannesburg and is compensated by the city.

Read: Eskom’s extraordinary turnaround

Sitting in the well-kept house he bought in 1996 and now shares with his wife, daughter and dog, Matubatuba says it’s practically impossible to get on the indigent register. Many of Yeoville’s residents are foreigners from as far away as Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of Congo; some of them are undocumented. But even South Africans feel defeated by the red tape.

“It’s a melting pot; all of Africa is here,” Matubatuba says as children play soccer on the street outside. “People will try and they will be given the runaround and then they give up.”

Johannesburg’s problems have been compounded by its inability to enforce laws and collect revenue, and by its failure to tackle the proliferation of illegal connections to the grid. (City Power says the unlawful connections are why it regularly cuts off power in Yeoville.) In July, activists that included Matubatuba’s group led a protest in the city centre over dissatisfaction with electricity services, and called for Gwamanda’s removal.

Johannesburg’s problems have been compounded by its inability to enforce laws and collect revenue, and by its failure to tackle the proliferation of illegal connections to the grid. (City Power says the unlawful connections are why it regularly cuts off power in Yeoville.) In July, activists that included Matubatuba’s group led a protest in the city centre over dissatisfaction with electricity services, and called for Gwamanda’s removal.

For now, Matubatuba and his neighbours have to endure what he says is an untenable situation. Many buildings in the overcrowded neighbourhood have been taken over by squatters, and power outages are causing crime to surge in what is already one of the city’s most dangerous areas.

There are “house and people robberies, muggings, hijackings of cars, killings by stabbing and shootings”, Matubatuba says. During outages, people also steal power cables — leading to blackouts that in some areas last even longer. — (c) 2024 Bloomberg LP