Google summoned about 200 policy staff from around the world last month for a debate on whether the company’s size has made it too attractive as a target for government regulators.

The two-day retreat in Monterey, California, where employees from the US$682bn (R9.3 trillion) company plied Washington policy experts with questions about the pros and cons of its size, took place as Google confronts European antitrust claims and proposed US legislation that would increase online publishers’ liability for content produced by others.

This week, the Alphabet unit disclosed new information that could further roil the regulatory picture: revelations that Russian-linked accounts used its advertising network to interfere with the 2016 US presidential election. The news put Google in the company of Facebook and Twitter, both of which are embroiled in the controversy surrounding Russia’s involvement in last year’s US elections. Executives at all three companies are scrambling to respond.

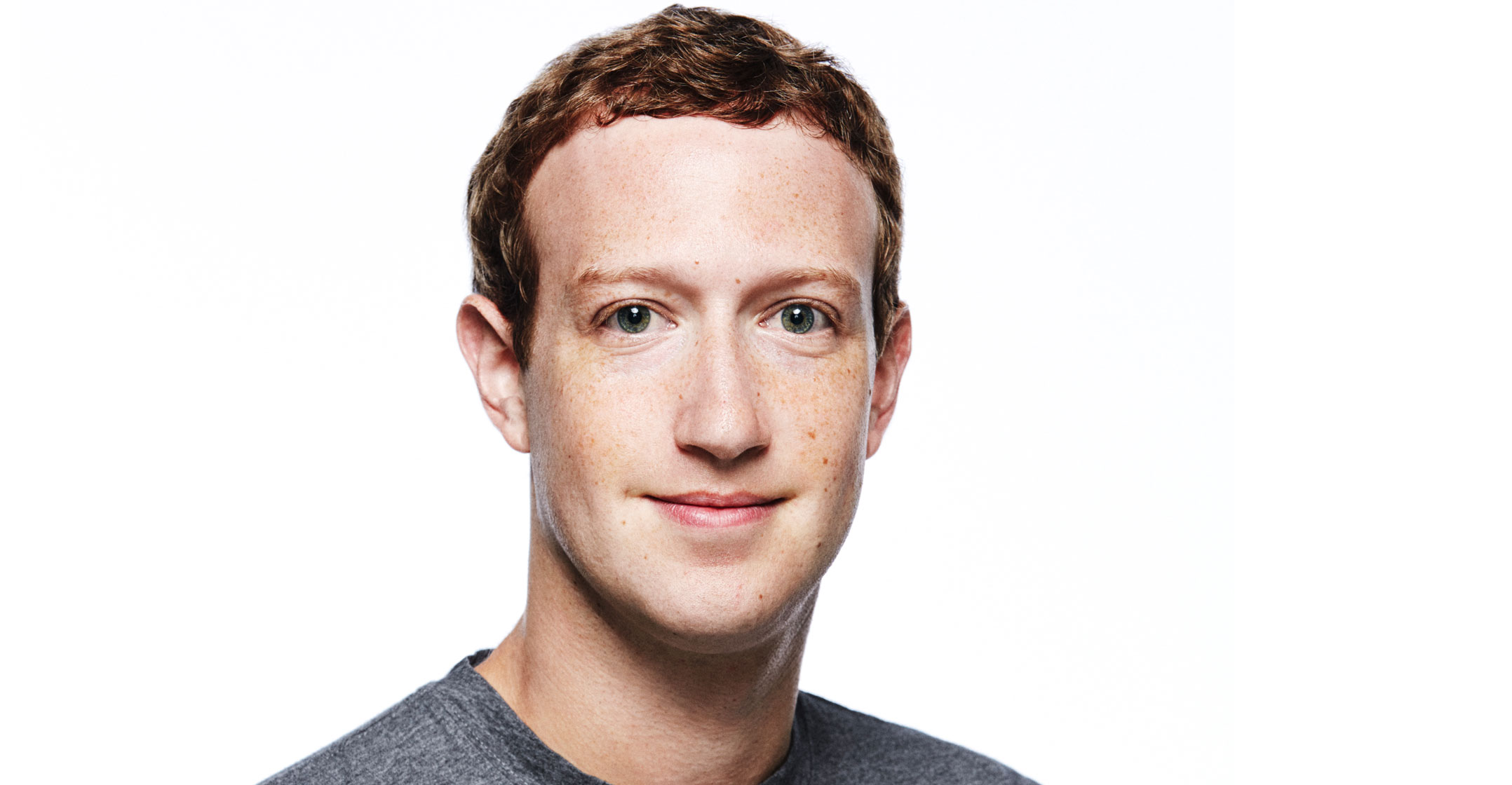

Facebook has hired two crisis PR firms, and it plans to bring on as many as a thousand people to screen ads. Top executives, including CEO Mark Zuckerberg, are phoning members of the US congress directly. The company reported spending more than $3.2m on lobbying in the first quarter of 2017, a company record. Google spent almost $6m in the second quarter for its own record. Both companies, with Twitter, are working together to deal with issues related to the Russian ads.

“There is a lot of pressure to intervene in this case because of the democratic implications,” said Laura DeNardis, director of the Internet Governance Lab at American University in Washington. “Because of the rising stakes for cyberspace, for the economy, for democracy, there is greater attention on the part of all actors.”

It’s a delicate balance for the companies, whose products reached massive scale because of their ability to transact advertising automatically, without much restriction. They must figure out how much responsibility to take and how much change to promise, without succumbing to costly regulation or setting a precedent that might be difficult to follow in other countries.

Political advertising

In the context of political advertising, some lawmakers are already proposing new limits. “We must update our laws to ensure that when political ads are sold online Americans know who paid for them,” Senator Amy Klobuchar, a Minnesota Democrat, said on Monday.

Two congressional committees and special counsel Robert Mueller are examining whether Russian operatives used social media platforms to influence US voters in 2016. Investigators are also examining possible collusion between Russian interests and associates of President Donald Trump. Facebook has turned over more than 3 000 ads purchased by Russian entities to both congressional investigations. Twitter has said it gave the panels a roundup of advertisements by RT, a TV network funded by the Russian government that was formerly known as Russia Today.

Facebook for years has sought exemptions from political-ad disclosure rules — but the company recently said it’s working on ways to show who pays for ads. It also indicated it might be open to some regulation regarding transparency.

For Google, the new concerns around political advertising come as it responds to European antitrust charges and tries to preserve online platforms’ liability protections under a law known as Section 230. A US senate bill aimed at stopping online sex trafficking has drawn opposition from Google, Facebook and other Internet companies because it weakens those protections. Google executives expected congress to be more receptive to its arguments that penalising knowledge of trafficking might stop smaller Internet companies from looking for it at all. They were caught off-guard by negative responses to the company’s lobbying, according to one Washington operative who works for the company.

Meanwhile, a potential showdown on political advertising looms on 1 November, when executives from Google, Facebook and Twitter have been summoned to Washington to give public testimony before congressional committees.

Facebook’s two top executives — Zuckerberg and chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg — have joined others in making calls to members of congress and trying to smooth relationships, the company said. It has also hired two crisis communications firms to help it on both Republican and Democratic fronts. And a letter went out to advertisers, saying Facebook staff would manually review ads that target people based on their politics, religion, ethnicity or social issues.

Facebook’s vice president of public policy, Elliot Schrage, started a question-and-answer-style blog called “Hard Questions” in June. In consultation with Liz Spayd, the former New York Times public editor, Facebook updates the blog when news breaks on the company’s relationship with the Trump campaign and the Russian ads.

On Sunday, when US television news show 60 Minutes aired an interview with the Trump campaign’s digital director saying he had partisan Facebook employees work as “ embeds” in the campaign, the company added an explanation of how its services for Trump were standard for any advertiser during an important event.

Reassurance

The strategy is meant to reassure the public, and lawmakers, that Facebook is working diligently on solutions and therefore doesn’t need to be regulated more. But some critics say that by volunteering to be responsible, Facebook is opening itself up to more publicity and more blame.

Inside the company, leaders are dismayed by how the public is interpreting its involvement in the Russia investigation, according to a person familiar with their thinking. Executives fear that Facebook’s work for the presidential campaigns is being reframed as partisan, for example, even though it offers the same services to any major advertiser.

Alex Stamos, Facebook’s chief security officer, defended the company from media critics who say it should have found a technical solution to the problem of fake news. It’s not that simple — and any quick solution could end up being ideologically biased, he said in a series of recent posts on Twitter.

Facebook, Twitter and Google are cooperating on issues related to the Russian political ads. A person familiar with the effort said it was similar to how the three firms would work together on difficult industry-wide issues, such as child pornography or content from terrorist groups.

“We are taking a deeper look to investigate attempts to abuse our systems, working with researchers and other companies, and will provide assistance to ongoing inquiries,” a Google spokeswoman said on Monday.

Twitter executives have been in frequent contact with congressional committees and investigators to try and answer their questions before 1 November, according to a person familiar with the matter. The company is addressing the issue from multiple angles, the person said, including asking engineers to examine spam-use on the platform and asking its advertising team to delve into ad purchases by RT, the Russian TV network.

Teaching Twitter’s algorithms to find malicious actors is challenging; Russian actors in particular are moving away from bots and networks to human beings that behave in coordinated ways, the person said. For instance, it can be difficult for Twitter’s algorithms to detect the difference between a group of paid tweets in Eastern Europe and a group of legitimate tweeters who are all posting at the same time at a convention.

Meanwhile, Google took a more creative approach to discussing its future last month. At the policy session in Monterey, one speaker played the opposition, voicing concerns about the power big corporations can wield over society. Another played defence. That was Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. His upcoming book, Big is Beautiful — co-authored by Michael Lind — argues larger firms create progress and prosperity.

“It was very open minded to have that kind of debate,” Atkinson said when reached by phone. “The threats against Google are certainly more severe now. Trying to portray yourself just as a good company is not adequate enough.” — Reported by Mark Bergen, Sarah Frier and Selina Wang, with assistance from Ben Brody, Gerrit De Vynck and Selina Wang, (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP