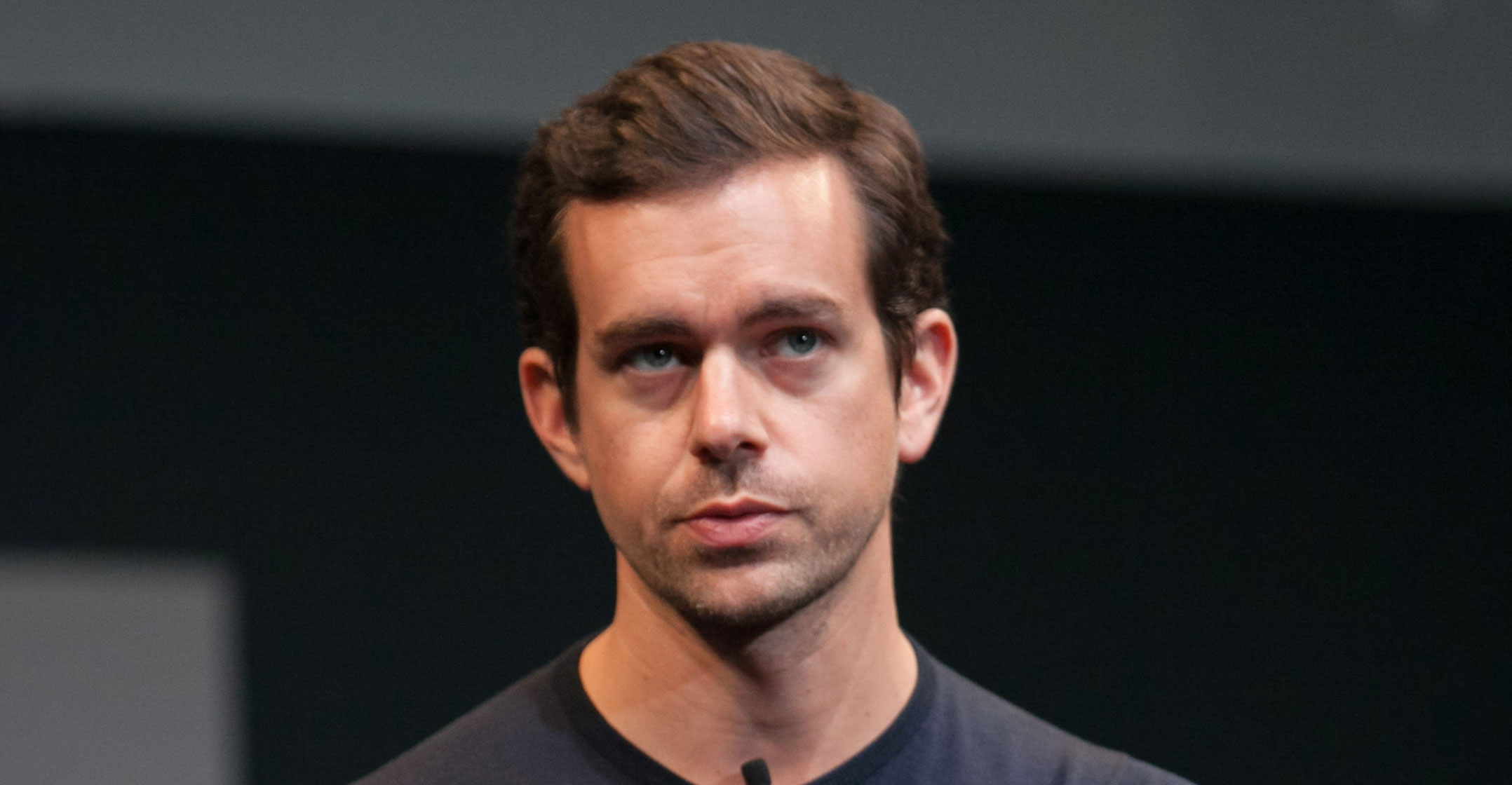

Facebook’s self-regulatory contortions in the wake of fake news and trolling scandals have gone on, with little visible effect, for months. Now Twitter founder and CEO Jack Dorsey has announced his company is going to try a different tack — but Dorsey’s approach is arguably even more far-fetched than his Facebook peer Mark Zuckerberg’s: it’s an attempt to view Twitter’s social mess as an engineering problem.

In a Twitter thread on Thursday, Dorsey admitted that Twitter has been home to “abuse, harassment, troll armies, manipulation through bots and human coordination, misinformation campaigns and increasingly divisive echo chambers” and that it’s not proud of how it has dealt with them. So, it would try to find a “holistic” solution through attempting to “measure the ‘health’ of conversation on Twitter”. The metrics, designed in collaboration with outside experts, would presumably help redesign the service so that all the bad stuff would be gone without the need for censorship.

That’s not how Facebook chose to handle a similar problem. For starters, it didn’t ask anyone for advice (Zuckerberg’s listening tour of the US doesn’t count because he didn’t specify as clearly as Dorsey what he was looking for). Facebook just devised some possible solutions such as working with fact-checkers to identify fake news and focusing on content from friends rather than publishers; it even experimented with putting publisher content in a separate newsfeed — a test it has just ended because users apparently didn’t want two feeds. It has also volunteered to reveal more information about who bought political ads.

It’s not clear whether these moves have done anything to fix the problems: I still have my tens of thousands of fake “subscribers” who showed up after I was active in the 2011 protests in Moscow and, as far as I’ve seen, questionable content from highly partisan sources is also still there. All that has happened is that, according to a recent analysis of Nielsen data by equity research company Pivotal Research Group, time spent by users on Facebook was down 4% year on year in November, 2017, and its share of user attention was down to 16.7% from 18.2% a year earlier.

Twitter, faced with a 14% decline in time spent and a decrease in attention share to 0.8% from 1.1% over the same period — and consequently described by Pivotal Research Group as a “niche platform” — needs to do something that will draw people to it, not repel them. So one can understand software developer Dorsey’s need for a bottom-up re-evaluation of how his software has been working.

The starting point has been provided by a nonprofit called Cortico, which grew out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab. It’s working on a set of “health indicators” for the US public sphere based on four principles: shared attention (to what extent people are interested in the same subjects?), shared reality (are people using the same set of facts?), variety (are people exposed to different opinions?) and receptivity (are they willing to listen to those different opinions?).

If there’s a transparently developed, openly discussed set of measurements to determine the “health of the conversation” on Twitter or any other social network, the networks could, instead of grappling with macro-problems like “fake news” or “harassment,” break down their responses into micro-actions designed to move the metrics. Then they could report to the public (and to concerned regulators) that the conversation is growing healthier.

Biggest problem

The biggest problem with this approach is a bit like the one with the World Bank’s Doing Business ranking, routinely gamed by authoritarian regimes’ officials who want to hit their performance indicators. According to this ranking, it’s easier to do business in Vladimir Putin’s Russia than in some EU countries, despite the absence of real guarantees that the business won’t be expropriated by a greedy law enforcement officer who happens to like it. Metrics are useful to managers because they give them a specific goal — moving a gauge by any means at their disposal. For the same reason, they can be useless to consumers, who will get what they see, which is not necessarily the same thing as what’s measured.

A secondary problem is that conversation can’t really be engineered algorithmically. Not even the Oxford Union rules of debate can be 100% successful in ensuring a civil dialogue, especially if the entities engaged in it are often anonymous and not always human. Dorsey has chosen to ignore the obvious problems — his platform’s dedication to full anonymity, the permissibility of multiple accounts for the same individual, the openness to automation — and take the roundabout route of trying to create a scorecard on which Twitter can be seen improving. This dashboard can be impressively high-tech, but human (or half-human, as the case may be) conversation really isn’t. “Social engineering” is a term for the low-tech manipulation of people into doing something they didn’t plan to do — like revealing their personal data or perhaps blowing up publicly so they can be shamed. Trolls are good at social engineering.

I banned several accounts with almost no followers today whose owners were trying to insult me. I do it every day. It’s unpleasant to deal with them, but under Twitter’s current rules it’s also unavoidable. A brief look at the responses to Dorsey’s thread (“You’re lying,” “‘This is not who we are’ translates to ‘This is EXACTLY who we are’,” “I’d tell you what I really think of you but you’d kick me off”) is enough to see what sort of conversational space Twitter is. Metrics? I’m sure they can be designed to show these comments are 77% “healthy” — and, for the next Dorsey thread, to show an improvement to 79%.

The point is worth repeating here: until it’s clear who’s talking on the social networks, just as it’s almost always clear with traditional media, and until there are real consequences to insults, harassment and intentional lies, the conversation cannot be healthy. It’s a bitter pill for the networks’ engineer founders, who tend to think technology and data can fix any problem, but a solution can only be found by putting people in the same environment that exists in face-to-face conversation or in the “legacy” news media — one that makes outbursts and lying legally and socially costly. — (c) 2018 Bloomberg LP