The latest US government action against China’s Huawei takes direct aim the company’s HiSilicon chip division — a business that in a few short years has become central to China’s ambitions in semiconductor technology but will now lose access to tools that are central to its success.

That could make it the most damaging US attack yet against a Chinese company that US officials told reporters on Wednesday functioned as a “tool of strategic influence” for the Chinese Communist Party. Huawei for its part denounced the US allegations and called the new measures “arbitrary and pernicious”.

Established in 2004, HiSilicon develops chips mostly for Huawei, and for most of its existence has been an afterthought in a global chip business dominated by US, Korean and Japanese companies. Like most electronics firms, Huawei relied on others for the chips that powered its equipment.

But heavy investment in research and development helped drive rapid progress at HiSilicon, and in recent years the 7 000-employee unit has been central to Huawei’s rise as a dominant player in the global smartphone business and the emerging 5G telecommunications networking business.

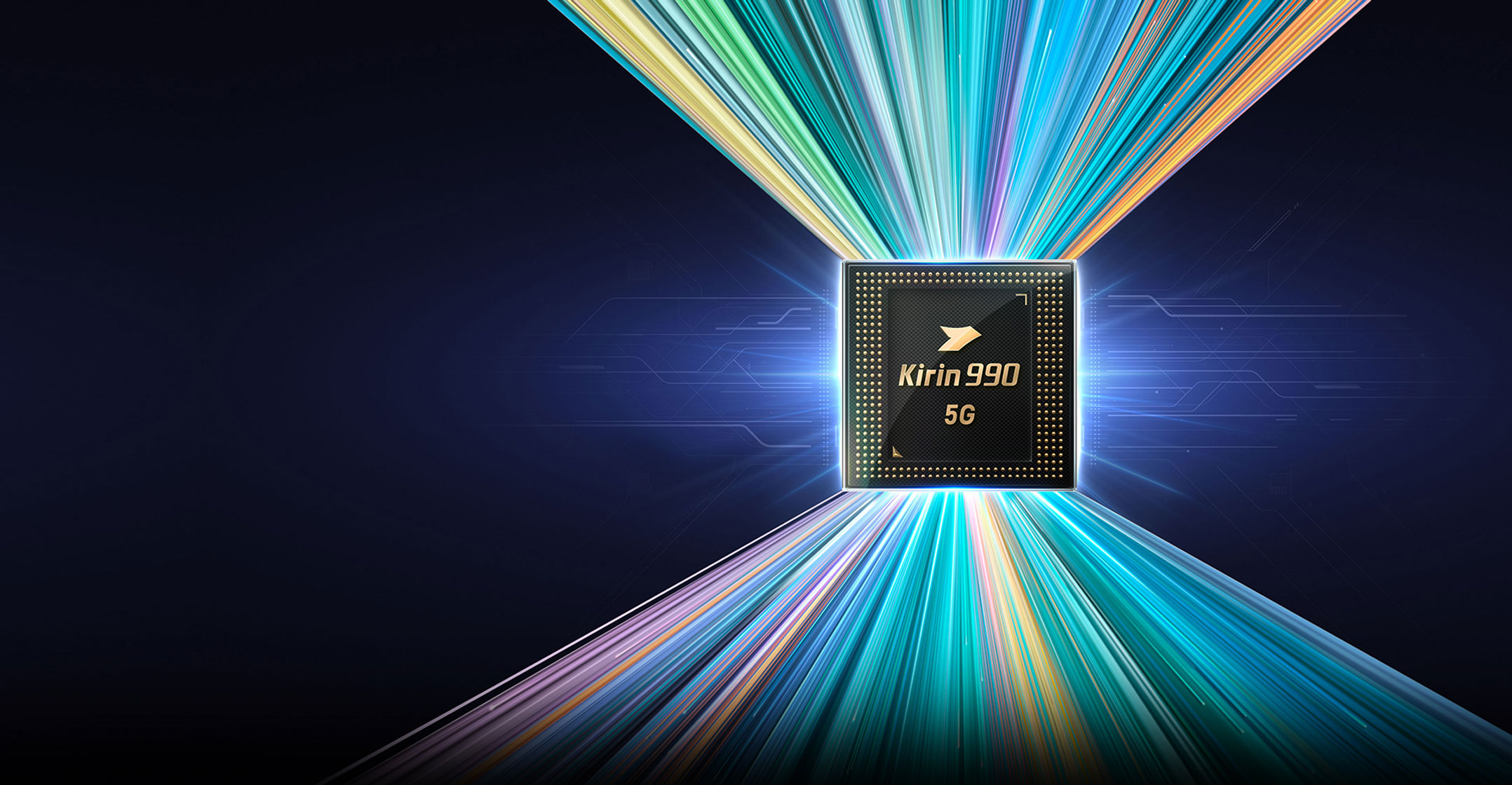

HiSilicon’s Kirin smartphone processor is now considered to be on par with those created by Apple and Qualcomm — a rare example of an advanced Chinese semiconductor product that competes globally.

HiSilicon is also central to Huawei’s leadership in 5G, stepping into the breach when the US cut off access to some US chips last year.

Crucial tools

In March, Huawei revealed that 8% of the 50 000 5G base stations it sold in 2019 came with no US technology, using HiSilicon chipsets instead.

But the US export control rule aims to block HiSilicon’s access to two crucial tools: chip design software from US firms including Cadence Design Systems and Synopsys, and the manufacturing prowess of “foundries”, led by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co, that build chips for many of the world’s top semiconductor firms.

With the new restrictions, HiSilicon “will be in a situation where they’re not able to manufacture chips at all, or if they do, then they’re not leading edge anymore”, says Stewart Randall, who tracks China’s chip industry at Shanghai-based consultancy Intralink.

Without its own processors, Huawei will lose its edge over domestic smartphone rivals, analysts said. International sales had already been gutted by a ban on the use of key Google software.

Without its own processors, Huawei will lose its edge over domestic smartphone rivals, analysts said. International sales had already been gutted by a ban on the use of key Google software.

Industry sources say Huawei has stockpiled chips, and the new US rule will not go into full force for 120 days. US officials also note that licences could be granted for some technologies. HiSilicon can also keep using design software it has already acquired.

Still, analysts agree HiSilicon is in a tough spot. Nearly all chip factories globally — including China’s leading foundry, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp — buy gear from the same equipment makers, led by US firms Applied Materials, Lam Research and KLA.

The new US rule requires licences for companies using US machinery to build Huawei-designed chips and delivered to the Chinese firm. To be sure, the new rule will not catch items shipped to a third party, allowing HiSilicon’s fabricators like TSMC the ability to ship chips to HiSilicon’s device manufacturers who can send them directly to a customer.

While there are alternatives to American machines — Japan’s Tokyo Electron, for example, makes gear that competes with Applied Materials — replacing US technology is not as simple as swapping out a machine.

“You almost have to think about it like a heart transplant,” said VLSI Research CEO Dan Hutcheson, noting that chip production lines are finely calibrated systems where everything has to work well together.

A few options

Doug Fuller of the Chinese University of Hong Kong said Huawei had a few options. It could slip around the rule by having suppliers ship directly to Huawei customers, though the US officials said they would be vigilant about such workarounds.

Huawei and the Chinese government could re-double efforts to build production capabilities that did not require US tools, by investing in nascent Chinese competitors and buying from Japanese and Korean firms, even if that required quality sacrifices.

Or Huawei could turn away from HiSilicon and revert to buying from overseas suppliers — just not American ones. “There’s talk of Huawei just turning to Samsung processors” for its smartphones, said Fuller. — Reported by Josh Horwitz, with assistance from David Kirton and Stephen Nellis, (c) 2020 Reuters