The US and China are moving beyond bellicose trade threats to exchanging regulatory punches that threaten a wide range of industries including technology, energy and air travel.

The US and China are moving beyond bellicose trade threats to exchanging regulatory punches that threaten a wide range of industries including technology, energy and air travel.

The two countries have blacklisted each other’s companies, barred flights and expelled journalists. The quietly unfolding skirmish is starting to make companies nervous the trading landscape could shift out from under them.

“There are many industries where US companies have made long-term bets on China’s future because the market is so promising and so big,” said Myron Brilliant, the US Chamber of Commerce’s head of international affairs. Now, they’re “recognising the risk”.

China will look to avoid measures that could backfire, said Shi Yinhong, an adviser to the nation’s cabinet and a professor of international relations at Renmin University in Beijing. Any sanctions on US companies would be a “last resort” because China “is in desperate need of foreign investment from rich countries for both economic and political reasons”.

Pressure is only expected to intensify ahead of the US elections in November, as President Donald Trump and presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden joust over who will take a tougher line on China.

Trump has blamed China for covering up the coronavirus pandemic he has mocked as “Kung Flu”, accused Beijing of “illicit espionage to steal our industrial secrets” and threatened the US could pursue a “complete decoupling” from the country.

Rare unity

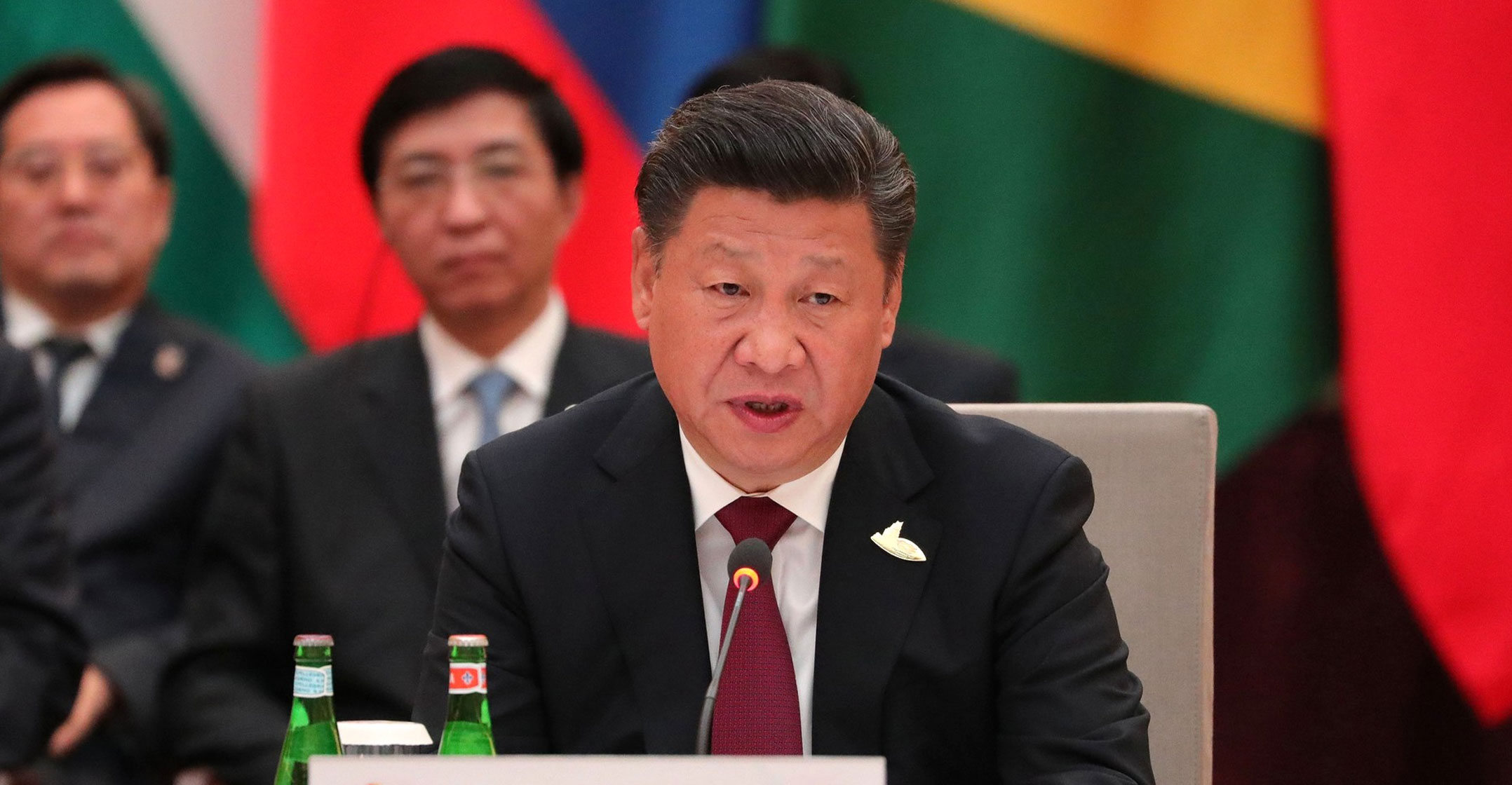

Biden, likewise, has described President Xi Jinping as a thug, labelled mass detention of Uighur Muslims as unconscionable and accused China of predatory trade practices.

And on Capitol Hill, Republicans and Democrats have found rare unity in their opposition to China, with lawmakers eager to take action against Beijing for its handling of Covid-19, forced technology transfers, human rights abuses and its tightening grip on Hong Kong.

“China is going to be a punching bag in the campaign,” said Capital Alpha Partners’ Byron Callan. “But China is a punching bag that can punch back.”

China has repeatedly rejected US accusations over its handling of the pandemic, Uighurs, Hong Kong and trade, and it has fired back at the Trump administration for undermining global cooperation and seeking to start a “new Cold War”. Foreign minister Wang Yi last month said China has no interest in replacing the US as a hegemonic power, while adding that the US should give up its “wishful thinking” of changing China.

Both countries have already taken a series of regulatory moves aimed at protecting market share.

Both countries have already taken a series of regulatory moves aimed at protecting market share.

The US is citing security concerns in blocking China Mobile, the world’s largest mobile operator, from entering the US market. It’s culling Chinese-made drones from government fleets and discouraging the deployment of Chinese transformers on the power grid. The Trump administration has also tried to constrain the global reach of China’s Huawei Technologies, the world’s largest telecommunications equipment manufacturer.

Meanwhile, China prevented US airline flights into the country for more than two months and, after the US imposed visa restrictions on Chinese journalists, it expelled American journalists. It has stepped up its scrutiny of US companies, with China’s state news agency casting one probe as a warning to the White House. China also has long made it difficult for US telecoms companies to enter its market, requiring overseas operators to co-invest with local firms and requiring authorisation by the central government.

One of the most combustible flashpoints has been the Trump administration’s campaign to contain Huawei by seeking to limit the company’s business in the US and push allies to shun its gear in their networks.

The US Federal Communications Commission moved to block devices made by Huawei and ZTE from being used in US networks. And the commerce department has placed Huawei on blacklists aimed at preventing the Chinese company from using US technology for the chips that power its network gear, including tech from suppliers Qualcomm and Broadcom.

After suppliers found workarounds, the commerce department in May tightened rules to bar any chip maker using American equipment from selling to Huawei without US approval. The step could constrain virtually the entire contract chip-making industry, which uses equipment from US vendors such as Applied Materials, Lam Research and KLA in wafer fabrication plants. The curbs also threaten to cripple Huawei. Although the company can buy off-the-shelf or commodity mobile chips from a third party such as Samsung Electronics or MediaTek, going that route would force it to make costly compromises on performance in basic products.

Spectre of reprisal

Huawei was on a list the Pentagon unveiled last week of companies it says are owned or controlled by China’s military, opening them to increased scrutiny.

China has raised the spectre of reprisal.

After the new restrictions were announced, the editor of the Communist Party’s Global Times newspaper tweeted that China would retaliate using an “unreliable entities list” that it first threatened at the height of the trade war last year. Although China didn’t identify companies on the list, the Global Times has cited a source close to the Chinese government as saying US bellwethers such as Apple and Qualcomm could be targeted.

The fallout could extend to companies heavily reliant on Chinese supply chains, as well consumer-facing brands eager to expand sales in Asia. Boeing, which recorded US$5.7-billion of revenue from China in 2019, and Tesla, the biggest US car maker operating independently in China, are among companies most exposed if relations sour further.

“We’re playing in a much wider field now,” said Jim Lucier, MD of research firm Capital Alpha Partners. “We’re not simply talking about ‘you tariff me’ and ‘I tariff you’, The playing field is virtually unlimited.”

“We’re playing in a much wider field now,” said Jim Lucier, MD of research firm Capital Alpha Partners. “We’re not simply talking about ‘you tariff me’ and ‘I tariff you’, The playing field is virtually unlimited.”

US automakers have also been singed. In June, China fined Ford’s main joint venture in the country for antitrust violations, saying Changan Ford Automobile had restricted retailers’ sale prices since 2013.

Aviation has been another source of tension, as both countries squabble over access to their skies. China’s decision to limit US airlines’ operations to those services scheduled as of 12 March hurt carriers such as United Airlines, Delta Air Lines and American Airlines that had suspended passenger flights to and from China because of the coronavirus pandemic.

De-escalation

The US responded earlier this month by initially threatening to ban all flights from China, then relenting to allow two flights weekly once Chinese officials eased their restrictions. Now, in what appears to be a staged de-escalation, China gave US passenger carriers permission to operate four weekly flights to the country and earlier this month, the Trump administration matched the move by also authorising four flights from Chinese airlines.

It’s happening outside of aviation, too. Consider the US government’s decision to seize a half-ton, Chinese-made electrical transformer when it arrived at an American port last year and divert the gear to a national lab instead of the Colorado substation where it was supposed to be deployed. That move — and a May executive order from Trump authorising the blockade of electric grid gear supplied by “foreign adversaries” of the US in the name of national security — have already sent shock waves through the power sector.

The effect has been to dissuade American utilities from buying Chinese equipment to replace ageing components in the nation’s electrical grid, said Jim Cai, the US representative for Jiangsu Huapeng Transformer, the company whose delivery was seized. Although Cai said the firm has supplied parts to private utilities and government-run grid operators in the US for nearly 15 years without security complaints, at least one American utility has since cancelled a transformer award to the company, Cai said.

Trump’s directive is tied to a broader effort to bring more manufacturing to the US from China. “This is a part of the administration’s efforts to impair China’s supply chains into the United States,” said former White House adviser Mike McKenna.

Escalating tensions could jeopardise the US economic recovery as well as China’s trade commitment to purchase $200-billion in American goods and services. Trump declared on Twitter last week that the pact “is fully intact”, adding: “Hopefully they will continue to live up to the terms of the Agreement!” Last week, Trump tweeted: “The China Trade Deal is fully intact. Hopefully they will continue to live up to the terms of the Agreement!”

It may also affect the November presidential election. Former US national security adviser John Bolton alleges in a new book that Trump asked his Chinese counterpart Xi Jingping to help him win re-election by buying more farm products — a claim the White House has dismissed as untrue.

“I don’t expect one single blow to send this relationship in a tailspin,” the chamber’s Brilliant said. “Each side will calibrate their reactions in a way that will not tip the scales too far.”

Take the recent spat over media access. After the US designated five Chinese media companies as “foreign missions”, China revoked press credentials for three Wall Street Journal staff members over an article with a headline describing China as the “real sick man of Asia”.

Then the Trump administration ordered Chinese state-owned news outlets to slash staff working in the US. Beijing responded in March by effectively expelling more than a dozen US journalists working in China.

Both the US and China have ample opportunities to ratchet up regulatory pressure. A bill passed by the senate last month could prompt the delisting of Chinese companies from US stock exchanges if American officials aren’t allowed to review their financial audits.

Visa bans

And last week, as the US state department imposed visa bans on Chinese Communist Party officials accused of infringing the freedom of Hong Kong citizens, a senior official made clear the move was just an opening salvo in a campaign to force Beijing to back off new restrictions on the city.

China, similarly, can slow licensing decisions and regulatory approvals, launch investigations under its anti-monopoly law and squeeze financial firms that want to do business in the country. For instance, the country could rescind pledges to let US financial firms take controlling stakes in Chinese investment banking joint ventures, according to a Cowen analyst.

“China will not make any significant compromise and will retaliate whenever and wherever possible,” Shi, the Renmin University professor, said.

Companies are still lured to China and its massive local market — and tensions with the US don’t overcome the Asian superpower’s appeal. Just one-fifth of companies surveyed by the American Chamber of Commerce in China late last year said they had moved or were considering moving some operations outside of the country, part of a three-year downward trend.

But the coronavirus pandemic has subsequently pushed more companies to reckon with the risks of relying too heavily on any single country for their supply chains, amid existing concerns about forced technology transfers, cost and rising tensions that could damp investment in China.

China is no longer the lowest-cost manufacturer, and companies are more reluctant to invest there, said James Lewis, director of the technology policy programme at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “Everyone would like to be in the China market — everyone wants it to be like 2010 — but things are changing.” — Reported by Jennifer A Dlouhy and Todd Shields, (c) 2020 Bloomberg LP