On paper at least, it makes sense. Telkom would use its far superior balance sheet to buy a weaker rival, giving its mobile business instant scale. It tried to buy its (then larger) rival in 2017.

Telecommunications, as we know, is a scale game. With 27 million subscribers, a combined operator will be better able to compete with MTN (28.9 million) and Vodacom (43.9 million). There are countless examples of markets around the world where four or five operators have consolidated down to three.

But the problem is that Cell C is arguably in worse shape today than it was two years ago when Telkom tried and failed.

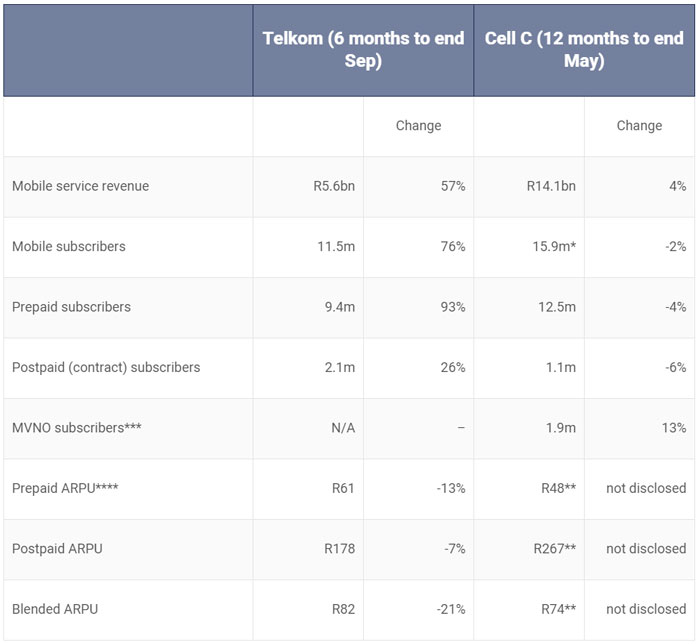

Revenue and subscriber growth has flat-lined — and earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) for the 12 months to end-May 2019 (aligned with the year-end of Blue Label Telecoms) was down 19%.

In this period, Cell C’s net loss before tax was R3.8-billion. The fundamental problem, even post recapitalisation, remains Cell C’s debt. At that point, it was R8.9-billion, 19% higher than a year prior. Net finance costs were R2.15-billion in the 12-month period.

It is not a stretch to suggest that Telkom’s mobile service revenue for the full year to end-March 2020 will be higher than Cell C’s for the same period. Further direct comparisons are difficult because of the way Telkom has restructured its business (its tower portfolio sits under Gyro and its core network, including fibre backhaul from towers, sits inside Openserve).

Debt problem

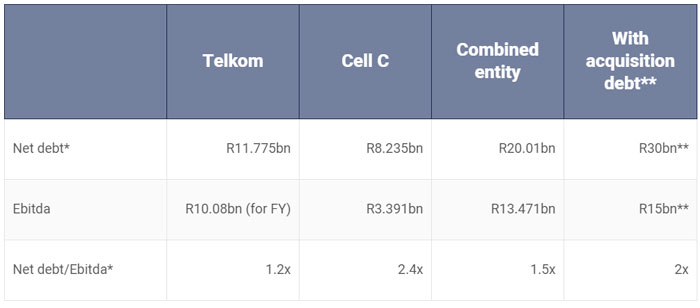

Any deal for Cell C has to resolve its roughly R9-billion debt problem, which is about R1.5-billion larger than it was last May. It didn’t add to its long-term borrowings in the year, but unfavourable currency movements meant a R600-million swing. On the short-term front, it has relied on a bridge loan from vendor ZTE, capitalised finance costs, and a facility increase to stay afloat.

Blue Label Telecoms paid R5.5-billion for 45%, and it doesn’t seem likely that a deal for Cell C will value the operator at anything more than R10-billion given the deterioration of its balance sheet and income statement since the recapitalisation.

Telkom group CEO Sipho Maseko may have some sort of ace up his sleeve. Cell C has accumulated tax losses in excess of R20 billion. Could this be central to a deal?

It is obvious that costs can be removed from Cell C, beyond those already taken out of the business since May. In fact, one could envision a scenario where, very simplistically, customers are migrated to Telkom’s network and practically everything else is shut down.

Beyond a subscriber base, it has brand equity, a store network (240-odd, many of which are franchises), a network in which it has woefully under-invested, and licensed spectrum. The two most valuable items to Telkom in this equation are the base and the spectrum.

Other expense increases in the business will be in line with revenues.

One way of looking at this is to calculate the amount of investment that is required in Telkom’s network to sustain growth in subscribers, and then to add to this the cost of acquiring customers via sales, marketing or incentives (and other overheads). Telkom knows exactly what this figure is in both the prepaid and post-paid space. It also knows the lifetime value of that active customer — that is, when they become profitable.

One way of looking at this is to calculate the amount of investment that is required in Telkom’s network to sustain growth in subscribers, and then to add to this the cost of acquiring customers via sales, marketing or incentives (and other overheads). Telkom knows exactly what this figure is in both the prepaid and post-paid space. It also knows the lifetime value of that active customer — that is, when they become profitable.

At a hypothetical R10-billion, the cost per customer acquired from Cell C would be around R650. But the debt needs to be factored in. Also, Cell C says its total assets are valued at R18-billion (with R12-billion of this ascribed to its network).

On paper, there are many ways to make the deal seem appealing (one can be certain a number of investment bankers are concocting complicated structures to make a deal work).

But Telkom would still have to assume Cell C’s debt, as a debt-for-equity swap seems far-fetched. Telkom could look to issue shares to raise capital, but neither this nor a debt for equity swap is likely to find favour with Telkom’s largest shareholder — government, directly via the department of communications (40.5%), and the Government Employees Pension Fund via the PIC (11.9%).

The assumption of Cell C’s debt, despite Telkom’s protestations that it has a “healthy” balance sheet, certainly stretches things to “interesting” levels. And this doesn’t factor in Telkom’s guidance which already sees net debt/Ebitda reaching 1.5 times in the next two years.

Add in a hypothetical R10-billion price tag for the acquisition (also funded by debt), and things start looking rather uncomfortable.

Telkom has some very serious issues to resolve in its own business, as detailed on Tuesday (read: As it bleeds fixed-line users, Telkom faces its day of reckoning). Its cash burn, negative free cash flow, and the reliance on debt to fund capex are all big warning signs.

Perhaps whatever Sipho Maseko has seen when looking over the cliff edge has him horrified. Executives have surely modelled out the decline of the fixed-line business. Numbers from these six months are really just the start. It is absolutely cratering and there’s no turning back.

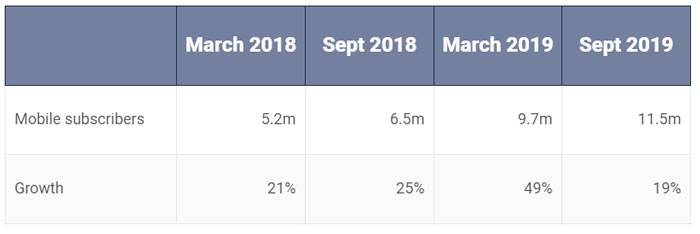

Until now, mobile has made up for the declines elsewhere but, worryingly, growth in mobile subscribers has slowed sharply in the last six months. BCX is going nowhere and fibre is not making up the losses elsewhere in its fixed-line unit, nor is it large enough yet to really move the needle. This has possibly forced Telkom’s hand.

Until now, mobile has made up for the declines elsewhere but, worryingly, growth in mobile subscribers has slowed sharply in the last six months. BCX is going nowhere and fibre is not making up the losses elsewhere in its fixed-line unit, nor is it large enough yet to really move the needle. This has possibly forced Telkom’s hand.

The question Telkom — and Maseko — must answer is where growth will come from. That might explain why it’s back at Cell C’s door.

- This column was originally published on Moneyweb and is used here with permission