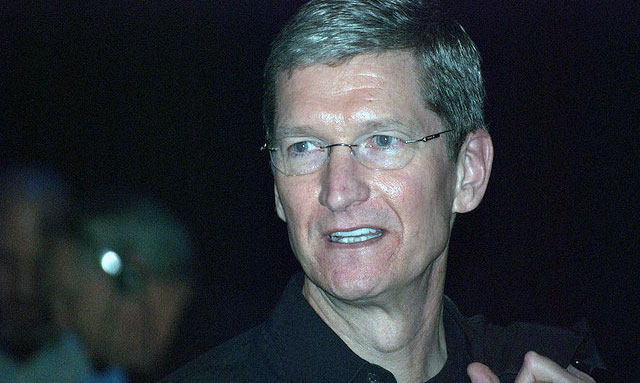

“We are always looking at acquisitions,” Apple CEO Tim Cook told analysts last month. “There’s not a size that we would not do.”

It’s a message he’s increasingly stressed over the past year as investors question how the world’s most valuable technology company plans to use its US$246bn (R3,2 trillion) cash pile to meet ambitious sales targets and expand into new markets, such as transportation.

But Apple has struggled for years to pull off bigger deals because of a series of quirks: an aversion to risk, reluctance to work with external advisers like investment banks, and inexperience in closing and integrating large takeovers, said people who have worked on acquisitions with the company. They asked not to be identified speaking about private merger and acquisition deliberations.

“The first step in M&A is having some conviction about what it is you want to do,” said Eric Risley, managing partner at Architect Partners who has negotiated deals with Apple. “Apple probably more than most feels that they’re very capable of building things” rather than buying them, he added. An Apple spokesman declined to comment.

Apple’s biggest deal in its 41-year history was the $3bn purchase Beats Electronics in 2014, followed by the $400m acquisition of NeXT Computer in 1996. In Facebook’s 13 years, it has made three acquisitions of at least $1bn, including its $22bn WhatsApp purchase. Google, founded in 1998, has done four such deals, while Microsoft has completed at least 10.

Instead of closing big deals, Cook has so far focused on growing Apple’s services businesses, including Apple Music, the App Store and iCloud. That’s beginning to work, with the company recently forecasting that annual revenue from those operations will top $50bn by 2021.

But even here, some analysts and investors argue for a big acquisition, especially in online video streaming. Apple has started distributing videos through the Music service, and pooling other providers’ video in its mobile TV app, but it has no service akin to Netflix or Amazon.com’s Prime Video.

On Friday, Sanford C Bernstein analyst Toni Sacconaghi said Apple needs at least one big acquisition in online video. To reach its $50bn target, the company must find an extra $13bn in services revenue over the next four years — beyond what it can generate itself. Netflix ended 2016 with sales of less than $9bn, so even buying that business may not be enough, the analyst said.

Other potential blockbuster Apple acquisition targets include Walt Disney and electric car maker Tesla, Baird analyst William Power wrote in a recent note to clients.

“They’re going to have to pursue something bigger than a Beats-like acquisition,” said Erick Maronak, chief investment officer at Victory Capital Management, which holds Apple stock among its $55bn under management.

The US presidency of Donald Trump may spark tax reforms that free up more Apple cash to spend on takeovers. But so far, the company has tiptoed around the edges of some of the biggest transactions reshaping the technology industry.

There’s a swagger — you may call it arrogance — about the culture there. They’re used to being able to muscle their way in and get attractive economics.

When AT&T agreed to purchase Time Warner for $85bn in October, the telecommunications company was concerned Apple might make a competing bid, people familiar with AT&T’s thinking said at the time. Apple had held tentative talks about a year earlier, but when the AT&T deal emerged, a person familiar with the technology giant’s thinking said it wouldn’t be able to pull together a competing proposal quickly enough.

Last year, the company considered buying luxury car maker McLaren Technology Group, people familiar with the discussions told Bloomberg at the time. Apple also had takeover talks with chip designer Imagination Technologies Group, but said last year it wouldn’t make an offer.

Apple’s deals team is composed of about a dozen people under former Goldman Sachs banker Adrian Perica, and most acquisitions take place at the behest of the company’s engineers. Product managers usually meet every month with Perica’s team members to identify targets with attractive technology or talented engineers, according to a person familiar with the process.

Microsoft’s deals team is not significantly bigger, and it still hired investment bank Morgan Stanley for its $26bn acquisition of LinkedIn last year, beating rival bidders including Salesforce.com and Facebook.

At Google, the corporate development team is led by Don Harrison and sometimes works on potential acquisitions with strategy experts working under chief business officer Philipp Schindler, not just technical staff. Other deals are carried out at the behest of founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin.

Apple often refuses to work with investment bankers appointed by the seller, preferring to deal directly with company management, according to people who have been involved in such negotiations. Apple also dictates terms and tells targets to take it or leave it, betting that the promise of product development support later and the chance of appearing in future iPhones are alluring enough, the people said.

That was the case when Apple acquired Metaio in 2015. Bankers appointed by the augmented-reality firm to negotiate weren’t allowed in the room, and while Metaio executives felt the offer was low, Apple’s vision for the technology convinced them to sell, according to a person familiar with the discussions.

Apple’s current M&A strategy works well for acquiring start-ups developing new technology that can be added to existing Apple products. It bought 15 to 20 companies per year over the last four years. But buying larger companies presents a different challenge, particularly if there are rival bids. Bankers often diffuse tension between bidders and targets, but Apple’s approach can make that process difficult.

“There’s a swagger — you may call it arrogance — about the culture there,” said Risley of Architect Partners. “They’re used to being able to muscle their way in and get attractive economics.”

For Apple’s acquisition of Beats, neither party used an investment bank. Apple struggled to integrate the team, and when the initial Apple Music offering emerged from the combination, it got lukewarm reviews. Later versions of the service improved. However, Apple’s lack of a successful track record integrating big acquisitions puts off sellers, according to a person who has negotiated with Apple’s deals team.

There are certain opportunities that they should probably be pursuing and if they wait too long they risk ceding ground to the first movers

Large acquisitions can also go wrong in big ways. After buying Nokia’s handset business for $9,5bn, Microsoft had to write down $7,6bn of that value in 2015. Failures like that helped forge Apple’s caution on larger deals, according to one of the people familiar with its thinking.

That attitude may need to change, according to some investors. After the AT&T-Time Warner deal, analysts’ focus shifted to Netflix as the next target, even as the video streaming service says it’s not up for sale. However, that company’s shares are up about 60% in the past year, giving it a market value of more than $60bn — 20 times the cost of Apple’s biggest deal.

“There are certain opportunities that they should probably be pursuing and if they wait too long they risk ceding ground to the first movers,” Victory Capital’s Maronak said. — (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP