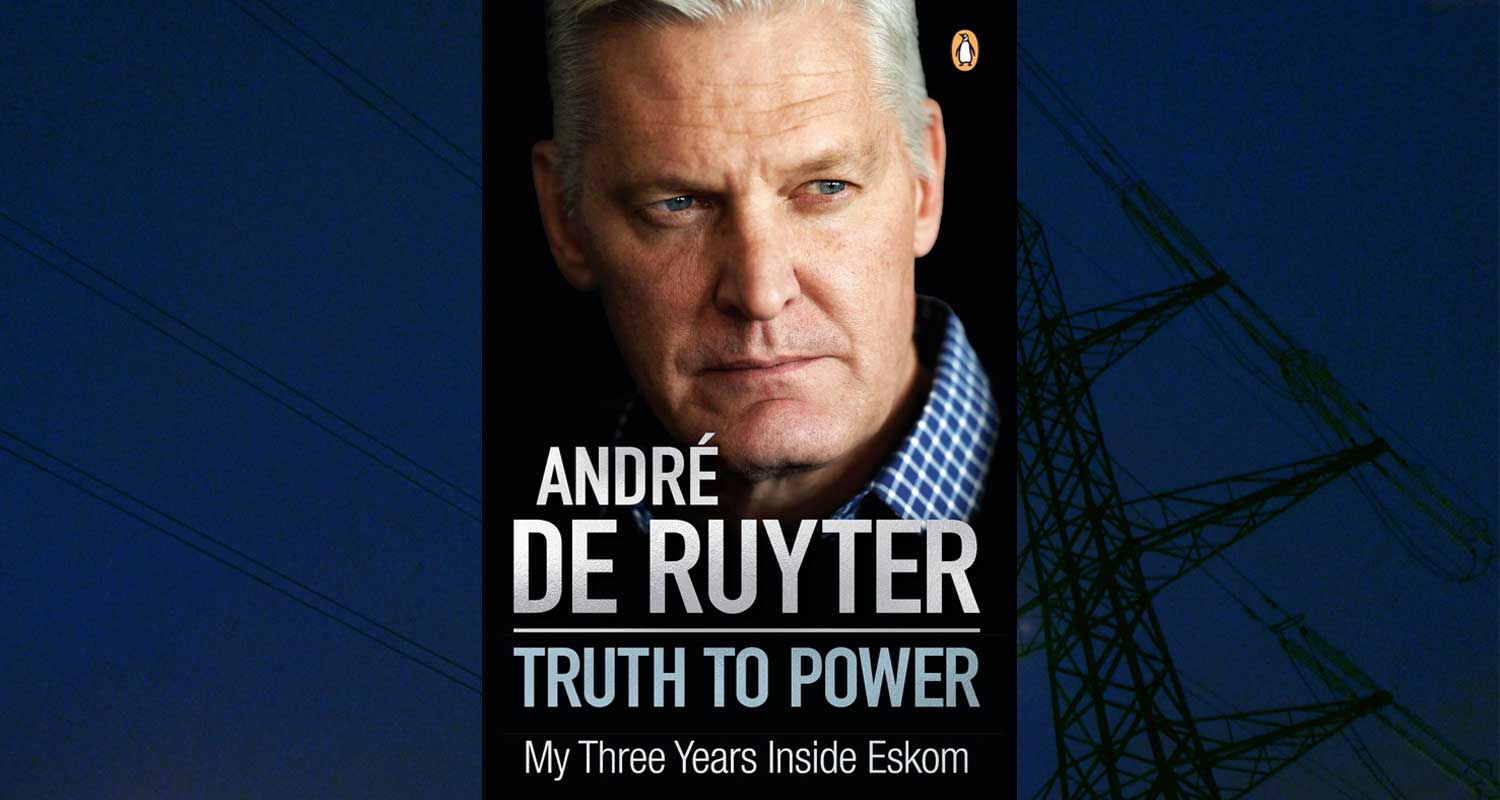

In Truth to Power, published on Sunday, three months after being sacked as Eskom CEO, André de Ruyter writes that decisions taken in 2007 will haunt South Africa for years to come.

In Truth to Power, published on Sunday, three months after being sacked as Eskom CEO, André de Ruyter writes that decisions taken in 2007 will haunt South Africa for years to come.

He is referring specifically to a Hitachi tender for boilers at Medupi and Kusile which should have been disqualified for a number of irregularities, but which was hurried through in only two weeks.

Initially the tender had been won by the French company Alstom, but rival bidder Hitachi didn’t take the loss lying down. Hitachi’s black economic empowerment partner was Chancellor House, the ANC’S investment firm.

“The Eskom team adjudicating one of the largest tenders for the new power stations showed a distinct lack of due diligence… Chancellor House was ultimately rewarded with R97-million for greasing Hitachi’s path to the tender. The R97-million included a ‘success fee’, dividends and eventually a share buyback.”

In 2009, Hitachi paid a US$19-million fine to the US Securities and Exchange Commission for contravening the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act – but this development was never investigated further by South African authorities. And due to faulty boiler specifications, signed off by one Matshela Koko, who was then the senior Eskom engineer responsible for boiler design, Medupi and Kusile became Eskom’s terrible twins, wreaking havoc with operational efficiency and its finances.

“For the ANC’S 97 million pieces of silver, the taxpayer is paying billions. Because of Kusile’s design flaws, we’ve lost around 2 100MW of generation capacity during 2023, enough to eliminate two stages of load shedding,” writes De Ruyter. “To fix only some of the boiler mistakes will cost R4.2-billion and we’ve already burnt R30-billion of diesel due to lost capacity.”

‘Common denominator’

De Ruyter writes that “all the spin doctoring and obfuscation in the world can’t hide that there is one common denominator to all these events, whether through policy failings, incompetence, state capture or corruption”.

As President Cyril Ramaphosa wrote to his ANC colleagues on 23 August 2020, the party and its leaders stood as “accused number 1 in the dock, accused of corruption”. But the ex-CEO says it is only the ANC that can indulge in this frank appraisal. “All others who dare point out what the president himself has acknowledged are publicly excoriated and calumniated (blamed).”

The tender bid mentioned above is just one of hundreds of examples of neglect, irregularities and corruption at the state-owned power company. But the ANC and Eskom have retaliated with vitriol.

Read: Eskom crisis to cost ANC dearly at the polls

Public enterprises minister Pravin Gordhan, De Ruyter’s former political principal, in an appearance before parliament on 17 May, heaped scorn on the former CEO and accused him of breaching the confidentiality clause of his employment contract. This was not the first time that Gordhan had criticised him for keeping the public informed.

At his first media briefing in January 2020, De Ruyter said South Africa needed extra generating capacity of between 4GW and 6GW as soon as possible – in the December before that, the country had experienced the worst-ever load shedding at stage 6. Gordhan called him afterwards and told him he had no right to share company information with the public.

Over the years, friction between Gordhan, a committed cadre and former member of the South African Communist Party, and the corporate-capitalist De Ruyter grew, culminating in the minister’s extraordinary attack on De Ruyter this week in parliament.

And in the 18 May briefing to discuss the state of the system and winter outlook, Eskom chairman Mpho Makwana used the word “repulsive” to describe De Ruyter’s behaviour, saying he broke the trust between himself and the company. He said the book broke a number of laws, including access to private information and corporate governance laws; the company secretary will take the book on legal review.

Nevertheless, in his book, De Ruyter acknowledges Gordhan’s integrity and that he is a disciplined party member who would never criticise his colleagues, except in the most oblique way. “For his bravery in taking on President Jacob Zuma and his cronies, Gordhan deserves the nation’s thanks. But it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that he is being hamstrung by his loyalty to the ANC. He knows something is amiss, but after 50 years in the struggle, it’s not easy to admit.”

Read: Gordhan undermined Eskom management: De Ruyter

The realisation dawned on De Ruyter after a meeting with police commissioner Fannie Masemola about the criminality and corruption at Eskom that he was sitting on more actionable intelligence than the country’s police chief. He had already commissioned a private investigation, but writes he didn’t want to play all his cards because the group of senior police officials and State Security Agency (SSA) agents was large and he wasn’t sure whom he could trust.

According to De Rutyer, Masemola told him everything he had just heard from the ex-Eskom boss was new to him – from sabotage to coal theft to illegal squatting in Eskom housing.

Ministers and even the National Prosecuting Authority took away cellphones during meetings to avoid possible interception

De Ruyter was in a quandary: who did he report his findings to? The police “mishandled even the simplest and most clear-cut cases we presented”, while the SSA allegedly admitted to having sat on explosive information for three years and acceded to a demand from a “highly placed politician” that the dossier be shared only with him. He suspected senior government officials might be involved themselves.

This is the nub of the accusations against De Ruyter: that he should dare to expose corruption at Eskom, but also link it to the ANC. At one stage Eskom had lodged 104 cases but there were only 12 prosecutions.

A feature of De Ruyter’s experience that is particularly worrying is the cloak and dagger experiences which were commonplace. Ministers and even the National Prosecuting Authority took away cellphones during meetings to avoid possible interception; he had to park far away from Gordhan’s house for a private meeting so that his presence wasn’t noted; and then there was the alleged attempt to poison him.

Read: Eskom corruption is killing South Africa

The detail and evidence in Truth to Power is comprehensive – not surprising when one hears that De Ruyter began collecting information for the book six months after taking over as CEO in January 2020, according to the Financial Mail.

“I’d make copious notes, so what I’d do was, every Sunday between about 8am and [midday] I’d get those thoughts down on paper.” This is not the action of a CEO who feels secure in his workplace, and one finishes his account of his three years at Eskom with a strong feeling of regret: that so much goodwill and energy was wasted and that so much unnecessary political interference and negligence has led to the impasse South Africa now finds itself in.

No doubt some of De Ruyter’s actions were contrary to the way ANC cabinet ministers conduct business and were deemed arrogant; no doubt he was perceived as impatient and no doubt he probably did contravene the confidentiality clause of his employment contract.

Energy minister Gwede Mantashe calls the book a “novel” that is “basically a diary, there is nothing novel about it — it’s a diary of meetings he has had”.

But be that as it may, De Ruyter felt that his hands were tied because he pursued every avenue open to him try to lance the poison at the heart of the Eskom corruption but was thwarted by political considerations. And since the current load shedding crisis affects every aspect of life for South Africans, they have a right to know some of the reasons for their predicament.

De Ruyter’s expose is obviously a subjective account of his experience at Eskom, and includes contemptuous observations about some South African cabinet ministers and politicians. However, it makes for fascinating reading with details and facts that certainly have more than a ring of truth to them. — (c) 2023 NewsCentral Media