Using a 3D printer is like printing a letter; hit the print button on a computer screen and a digital file is sent to, say, an inkjet printer which deposits a layer of ink on the surface of a piece of paper to create an image in two dimensions. In 3D printing, however, the software takes a series of digital slices through a computer-aided design and sends descriptions of those slices to the 3D printer, which adds successive thin layers until a solid object emerges. The big difference is that the “ink” a 3D printer uses is a material.

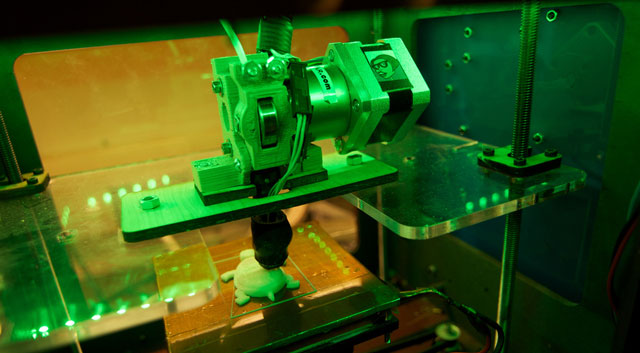

The layers can come together in a variety of ways. Some 3D printers use an inkjet process. Objet, an Israeli 3D-printer company, uses the inkjet head to spray an ultra-thin layer of liquid plastic onto a build tray. The layer is cured by exposure to ultraviolet light. The build tray is then lowered fractionally and the next layer added. Another way is fused deposition modelling, a system used by Stratasys, a company based in Minneapolis. This involves melting plastic in an extrusion head to deposit a thin filament of material to build the layers.

Other systems use powders as the print medium. The powder can be spread as a thin layer onto the build tray and solidified with a squirt of liquid binder. It can also be melted into the required pattern with a laser in a process called laser sintering, a technology which EOS, a German firm, uses in its additive-manufacturing machines. Arcam, a Swedish company, fuses the powder in its printers with an electron beam operating in a vacuum. And these are only some of the variations.

For complicated structures that contain voids and overhangs, gels and other materials are added to provide support, or the space can be left filled with powder that has not been fused. This support material can be washed out or blown away later. The materials that can be printed now range from numerous plastics to metals, ceramics and rubber-like substances. Some machines can combine materials, making an object rigid at one end and soft at the other.

Some researchers are already using 3D printers to produce simple living tissues, such as skin, muscle and short stretches of blood vessels. There is a possibility that larger body parts, like kidneys, livers and even hearts, could one day be printed — and if the bio-printers can use the patient’s own stem cells, his body would be less likely to reject the printed organs after a transplant.

Food can be printed, too. Researchers at Cornell University have already succeeded in printing cupcakes. The “killer app” with food, almost everyone agrees, will be printing chocolate. — (c) 2012 The Economist![]()

- Image: Kakissel/Flickr