Sunny countries are often poor. It is a shame, then, that solar power is still quite expensive. But it is getting cheaper by the day, and is now cheap enough to be competitive with other forms of energy in places that are not attached to electricity grids. Since 1,6bn people are still in that unfortunate position, there is now a large potential market for solar energy. The problem is that although sunlight is free, a lot of those 1,6bn people still cannot afford the upfront cost of the equipment in one go, and no one will lend them the money needed to buy it.

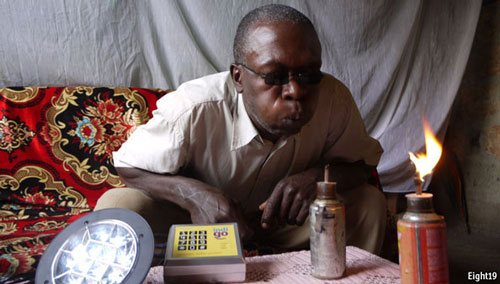

Eight19, a British company spun out of Cambridge University, has devised a clever way to get round this. In return for a deposit of around US$10, it is supplying poor families in Kenya with a solar cell able to generate 2,5W of electricity, a battery that can deliver a 3A current to store this electricity, and a lamp whose bulb is an energy-efficient light-emitting diode. The firm reckons that once the battery is fully charged, this system is sufficient to light two small rooms and to power a mobile-phone charger for seven hours. Then, the next day, it can be put outside and charged back up again.

The trick is that, to be able to use the electricity, the system’s keeper must buy a scratch card — for as little as a dollar — on which a reference number is printed. The keeper sends this reference, plus the serial number of the household solar unit, by text message to Eight19. The company’s server will respond automatically with an access code to the unit.

Users may feel as though they are paying an hourly rate for their electricity. In fact, they are paying off the cost of the unit. After buying around $80-worth of scratch cards — which Eight19 expects would take the average family about 18 months — the user will own it. He will then have the option of continuing to use it for nothing, or trading it in for a bigger model, perhaps driven by a 10W solar cell.

In that case, he would then go through the same process again, paying off the additional cost of the upgraded kit at a slightly higher rate. Users would thereby increase their electricity supply — ascending the “energy escalator”, as Eight19 puts it — steadily and affordably. Simultaneously, the company would be able to build a payment record of its clients, sorting the unreliable from the rest.

According to Eight19’s figures, this looks like a good deal for customers. The firm reckons that the average energy-starved Kenyan spends about $10/month on paraffin — sufficient to fuel a couple of smoky lamps — plus $2/month to have his mobile phone charged at a nearby market. Regular users of one of Eight19’s basic solar units will spend around half that, before owning it outright. Meanwhile, as the cost of solar technology falls, the whole system should get even cheaper. The company hopes to be able to supply users with a new, low-cost and robust sort of solar cell, printed onto plastic strips, within two years.

So far the scheme has been tried out among a couple of hundred Kenyan families. With the aid of a charitable loan to accelerate its roll-out, Eight19 is now in the process of dispersing another 4 000 solar units in Kenya, Malawi and Zambia. If its novel idea works, solar power will come within reach of a whole new set of customers — and the days of the paraffin lamp could well be numbered. — (c) 2012 The Economist![]()

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Google+ or on Facebook

- Visit our sister website, SportsCentral (still in beta)