As scandals go, it is a corker. It involves secret recordings of lobbyists talking to tycoons about ministers, fraudulent documents, unrelated firms that share the same e-mail address, clueless foreigners piling into a vast market, bank drafts with dates that make no sense, PR flacks taped schmoozing hacks with honking traffic in the background, front companies named after Russian rivers, an apparently helpless prime minister, people under arrest and something between US$8bn and $20bn pinched from the public purse.

India’s telecoms scandal has been rumbling since 2008, when 122 mobile licences covering a third of India’s 2G spectrum were awarded to eight companies. (India today has 14 mobile-phone firms in all.) A constant drip of disclosures since then has numbed the public’s outrage. But on 2 February, India’s supreme court cancelled all 122 licences. Its 94-page ruling is required reading for anyone interested in doing business in India.

Politically, the scandal’s effects are not yet known. Andimuthu Raja, the telecoms minister at the time, is in jail. His trial could reveal all manner of dirt. The coalition government, led by the Congress party, is shaken, though its supporters hope no other big scalps will be claimed. State elections, the results of which are due on 6 March, will measure voters’ wrath.

From a business perspective, two conclusions can be drawn. The first is a cheering one: India’s legal system seems to be working just fine at the very top. The second is less sunny: the mobile-phone industry faces turmoil. There is also a worrying question: is the smell from the telecoms business a sign of a deeper rot?

From cellphones to prison cells

Along with outsourcing, mobile telecoms is India’s biggest industrial success story. Every emerging economy has seen a mobile boom, but India’s was huge. It spawned a national champion: Bharti Airtel (which is untainted by the affair). Indian firms rewrote the rule book, cutting tariffs lower than others had dared and outsourcing parts of their operations. The spread of phones to slums and villages created a social revolution.

That boom, though, contained the seeds of the scandal. Mobile spectrum, which was in short supply, became very valuable. Between 1994 and 2007, four phases of licensing took place. The government tried different ways of allocating airwaves, from beauty parades and auctions to operators making upfront payments to the state. (Most rich countries stick with auctions, since they are simple, transparent and hard to cheat.)

By 2007, the process had become a shambles. Applications for licences languished in government files. On 23 September 2007 ,the department of telecommunications was sitting on 167 of them. (India’s regime splits the country into 23 regions, so each firm typically seeks multiple licences.)

The next day, the department said any further applications would need to be received by 1 October. Another 408 applications were hurriedly made.

What happened next, according to the supreme court, “leaves no room for doubt that everything was stage-managed”. The deadline was retroactively changed. Those on the shortlist announced on 10 January 2008 were given just hours to respond to the news. Of the 16 firms on that list, 13 mysteriously already had bank drafts ready to pay the nominal upfront fee, which were dated before the public announcement had been made, according to India’s Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG). It reckoned they were given advance notice. It also noted that 13 of the 16 firms made “false and fictitious” statements about their finances.

Safeguards failed. Requests for advice from other arms of the state circulated, but behind this mirage of due process, the department of telecommunications was out of control. To evade scrutiny from its critics inside the government, the department delayed a meeting and announced its decision before the rescheduled date. In 2007, Raja, the safari-suited telecoms minister, received a cringingly meek letter from the prime minister, Manmohan Singh, expressing concern. Within hours he bashed out a dismissive reply and carried on regardless. Of the 122 licences granted, 85 went to six new entrants, including several property firms, two of which promptly made fortunes by selling stakes in the licences to foreigners. CAG found that a year later none of the six had met its obligation to roll out a network.

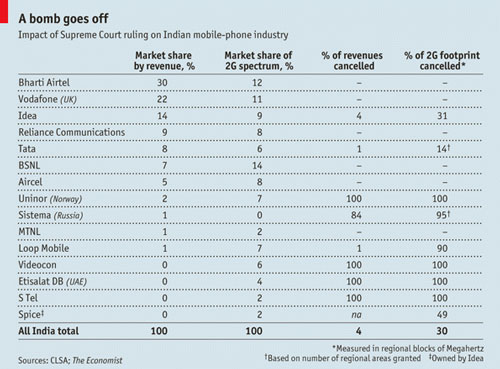

For the telecoms industry, the judgment creates chaos. The cancelled spectrum must be returned within four months, and then auctioned off. After a bout of mergers it is now in the hands of eight firms and affects 67m customers (7% of India’s total) and 30% of 2G spectrum capacity, according to Deepti Chaturvedi of CLSA, a broker. Six of those firms could fail without the suspect licences (see table below). One executive reckons the total capital invested by those half-dozen in acquiring customers and kit might amount to $10bn.

Their legal position appears weak: a buyer of illegitimately acquired goods has no one to blame but himself. Worryingly, though, the Indian government is making soothing noises to these firms, as if the way to improve India’s investment climate is to rescue foolish investors.

If principle wins out, the best these firms can expect is to be allowed to sell their customers and kit to the remaining operators and be refunded the modest fees they paid to the government; or, if they are still keen and not incriminated by other cases, to be allowed to bid in fresh spectrum auctions. The court has demanded those auctions take place as soon as possible. To be credible they should be open to all operators, and the highest bidders should win, subject to antitrust limits. This may benefit the big fish. But even after the exit of smaller fry there would still be six or seven big firms competing — plenty by global standards. India has proved it can hold clean auctions: a 3G one in 2010 was widely praised.

By insisting that an auction is the only fair way to allocate spectrum, the supreme court has cast into question other licences granted before 2009 by different means, including those of Reliance Communications and the Tata group, two giant firms. And there are grave doubts about the telecoms bureaucracy. “There is no reason to believe much has changed,” says one executive. “They have completely lost the plot,” says another.

Once a freewheeling industry, mobile is fast maturing, with sedate growth and high levels of debt, partly as a result of those 3G auctions in 2010. All operators bar one, Bharti Airtel, make weak returns on capital in India. Yet for bureaucrats, mobile is still something to be controlled. The department of telecommunications and TRAI, the regulator, want to lean on operators to buy more of their kit from local manufacturers. They are also talking about officials setting tariffs. Reports of the death of the licence Raj were greatly exaggerated, it seems.

On 3 February, the prime minister, who is widely held to be clean, said the country had moved “substantially forward” in dealing with corruption, but that there was still “a long way” to go. He hopes to pass an anti-corruption bill — though this has so far been blocked by bickering in parliament. Some Indians think that all this is a healthy sign of a free and noisy democracy at last getting to grips with a problem. Some protest that the scale of graft has been exaggerated.

Yet after the 2G scandal that is surely a complacent view. It has taken the courts, not the political system, to act. Industry seems to be gripped by a culture of denial. Executives make pious statements in public and sling mud in private. There is anecdotal evidence that corruption is rife in most industries that interact with the government: those that require licences, access to natural resources or changes in the law.

One government mandarin talks of a vast backlog of vital projects, such as mines and industrial plants, some of them half-finished, that break current rules and are possibly bent. Officials don’t know whether to turn a blind eye or blow their whistles and cause mayhem. The suspicion of widespread graft is corrosive for business. Is it safe to take over another firm or is it a legal time bomb? Do investors dare give cash to an indebted company with a ripe reputation but a promising project? Can a foreign firm ever be sure that its Indian partner is clean? These are uncomfortable questions. — (c) 2012 The Economist![]()

- Image: vgrigas/Flickr

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Google+ or on Facebook

- Visit our sister website, SportsCentral (still in beta)