Going just by the stock prices of its peers, the interesting thing about Apple isn’t that it’s worth US$1-trillion. It’s that it’s not worth more.

Not that investors are complaining — this week, anyway — after a buoyant sales forecast supercharged the stock and made it the first US company with a 13-digit capitalisation. Apple beat out fellow “Faang” Amazon.com, which has about $105-billion to go before reaching the milestone.

But while Apple is a Faang, in key respects it is different — particularly valuation. Comparatively speaking, its earnings don’t get anywhere near the respect of its megacap brethren. At $56-billion, profits in the past year are double the next biggest earner in the Nasdaq 100 Index. But its price-earnings ratio trails 70% of the gauge’s members.

Put it this way. If Apple’s income was treated with the same generosity bestowed on companies like Alphabet and Facebook, its value would be closer to two trillion than just one.

The reasons it isn’t are well known. Apple’s bread and butter is hardware, unlike Google and Microsoft. And while nothing to sneeze at, its profit growth is running at about half the rate of Amazon. Creeping pressure on margins has raised concern about how booming future profits will be.

Another thing to consider is how large a company is likely to get relative to the economy itself. On that basis, many of today’s technology titans are in rarefied air.

At 4.9% of US GDP, Apple’s relative value has been surpassed by only two companies in decades past. One was Microsoft, which topped out around 6% in 1999. The other was General Electric, whose value in 2000 came out to more than 5% of the US economy.

The data illustrate a challenge for Apple at a time when nine out of 10 Americans already own a cellphone. After 13 straight years of uninterrupted sales growth ended in 2016, CEO Tim Cook has embarked on a strategy to sell a growing array of services through a base of more than 1.3 billion Apple devices. But boosting annual sales that are already over $200-billion is hard.

‘Tall order’

“How on earth are you going to double your money on Apple?” said Ethan Anderson, a senior manager who helps oversee $1.5-billion at Rehmann Financial in Grand Rapids, Michigan. “Absent any type of change in margin, they in theory would have to gain an additional $250-billion of revenue. That’s quite a tall order.”

In most respects, Apple’s subdued p:e reflects concern over profit margins. Investors are unwilling to pay up for earnings, fretting that intensified competition in a saturated market will crimp profitability. Measured against sales, the stock is valued pretty much in line with the market. Its multiple of 4x puts it in the middle of the pack among Nasdaq 100 firms.

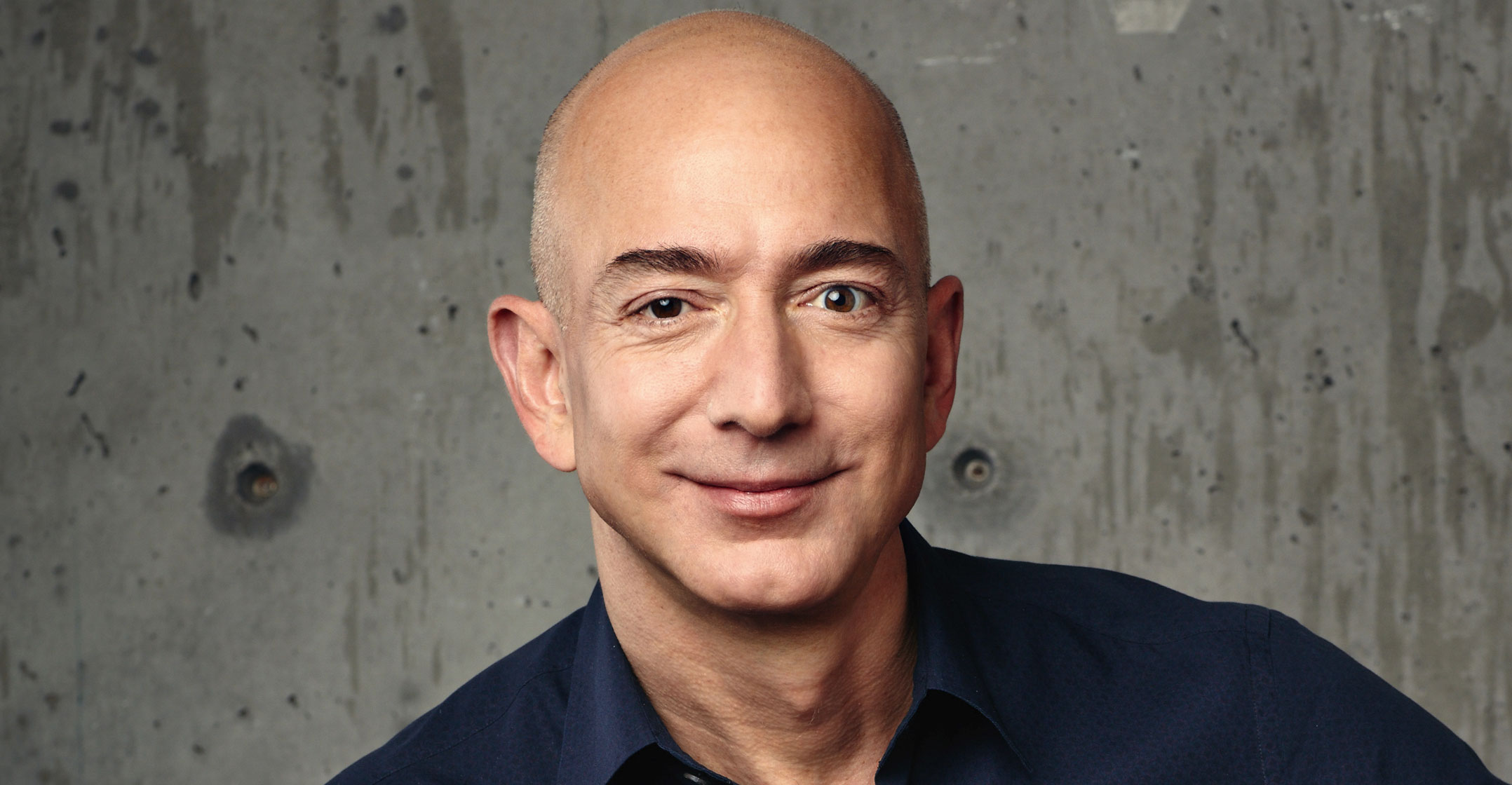

From a valuation perspective, Apple is a vastly different animal than a company like Amazon. A retail behemoth that maniacally held down profit margins for all of its 24-year existence, Jeff Bezos’s online superstore is expected to earn a comparatively paltry $8-billion in 2018. That’s good for a p:e ratio of 105 — a sign of the enormous faith Wall Street puts in founder Bezos to execute his vision.

“There is a lot more growth expectation embedded in Amazon shares than Apple,” said Matt Lockridge, a Dallas-based senior portfolio manager at Westwood Management. “Amazon is the leader in arguably the two most sector-exciting categories, and that’s Internet commerce and cloud computing. Secular growth in both is very attractive and they hold the number one position. Apple is in a more concentrated number of product categories.”

Since the iPhone’s introduction in 2007, Apple has launched few blockbuster products despite forays into areas such as watches and televisions. Cook, who succeeded Steve Jobs in 2011 just before the founder’s death, has yet to show the company can evolve beyond its reliance on a device that accounts for more than 60% of revenue.

“Unless everyone is going to carry two iPhones around, to double from here is going to be exponentially hard,” said Michael Ball, president and lead portfolio manager of Denver-based Weatherstone Capital Management. “It’s too risky to totally change your business model. But if you don’t innovate, someone picks on the things you passed on and eventually surpasses you.” — Reported by Lu Wang, (c) 2018 Bloomberg LP