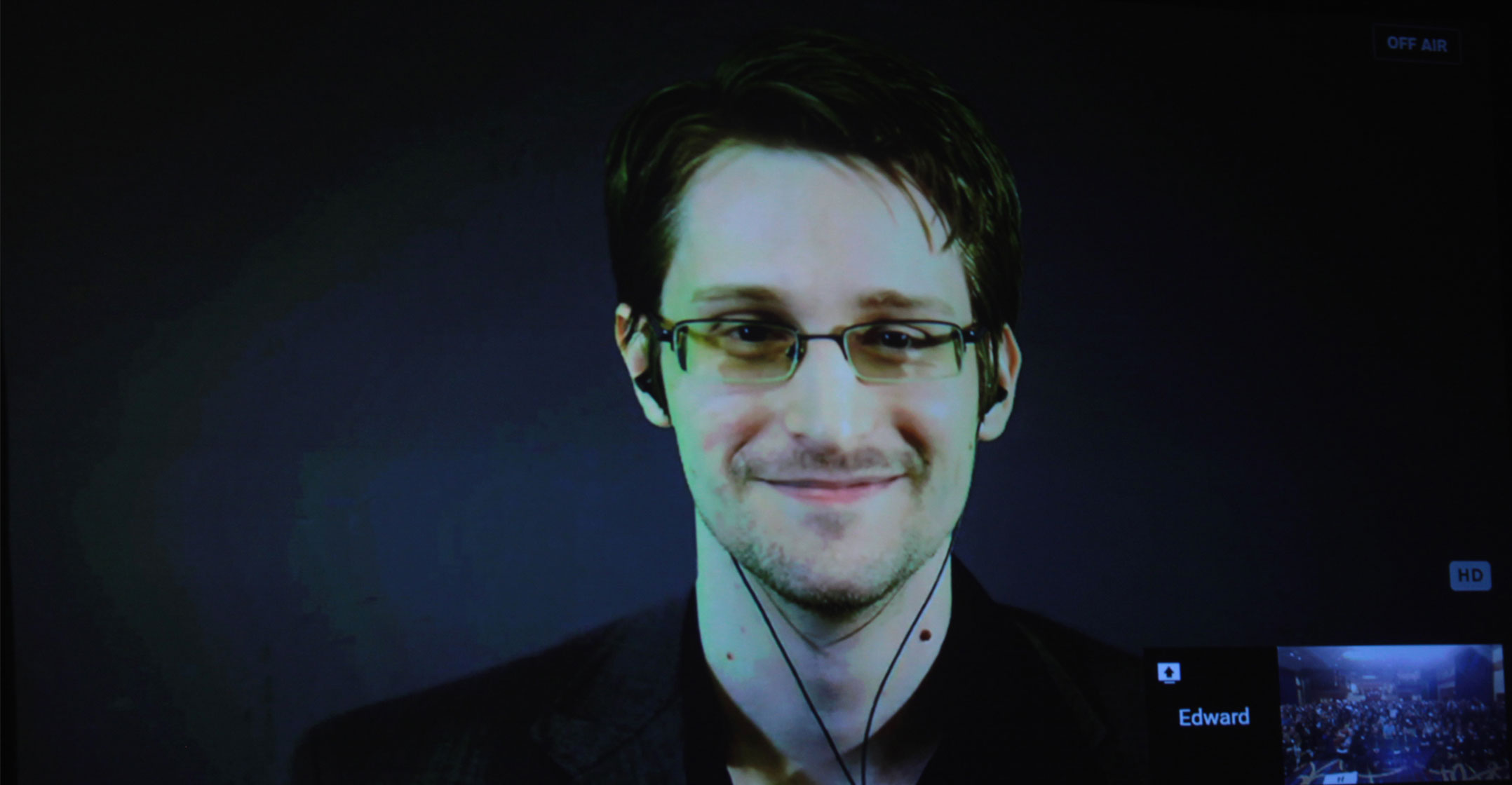

Do you remember the NSA’s phone-records programme? It was perhaps the most contentious of Edward Snowden’s revelations, and became the subject of a vicious multiyear imbroglio in the US congress. Now the operation has been halted entirely — with barely a whimper.

Section 215 of the Patriot Act authorised the government to collect a broad range of business records relevant to terrorism investigations. The National Security Agency took this to mean that it should collect the phone records of effectively every American — on the theory that they could all one day be “relevant” — and store them in a searchable database.

In every respect, this programme was an outlier. Unlike other operations that Snowden illegally revealed, it intentionally swooped up records from US citizens. It collected data in bulk, rather than targeting individuals. It had a highly dubious legal rationale. And, most pertinently, it didn’t really work: two comprehensive reviews of the programme — both based on classified information — concluded that it had not played an essential role in any terrorism probe.

So when congress sought to reform the government’s surveillance powers, starting in 2014, the phone-records programme was a natural priority. A bipartisan bill that would’ve ended its most objectionable aspects — while still ensuring that the NSA could access needed records — quickly gained support. Known as the USA Freedom Act, it had the backing of the White House, much of congress, privacy advocates, civil liberties groups, Silicon Valley and, not least, the intelligence community itself.

Even so, some senators expressed horror. The bill would “put the country at risk”, fumed Orrin Hatch. It amounted to “a resounding victory for those currently plotting attacks against the homeland”, said Mitch McConnell. For good measure, Marco Rubio invoked the Islamic State: “God forbid we wake up tomorrow and ISIL is in the United States.”

Nevertheless, the reform passed. It made the NSA’s job slightly harder by requiring a court order to get targeted records from phone companies. But in return, it protected Americans’ privacy, and ensured the programme was on sound constitutional footing. More than a decade after 11 September, it was a prudent rebalancing of liberty and security.

Unceremonious end

Last week, rather unceremoniously, it emerged that the whole thing had been shut down. A congressional aide blurted out on a podcast that the NSA hadn’t been using the tool for months. Donald Trump’s administration may not even seek to renew its authorisation when it expires at the end of the year. “We are in a deliberative process right now,” the agency’s director conceded on Wednesday.

Yet the country still stands. For all the dire warnings, the NSA has been able to do its job without the programme. In part, that may be because terrorists have shifted from traditional phones to encrypted messaging services. But that trend was fully predictable — indeed, underway — when Rubio was warning about a looming invasion.

A lesson suggests itself. Even in the best of times, reforming intelligence agencies is an immense challenge. It requires good faith, clear thinking, sober risk assessment and a judicious evaluation of competing values. Theatrical alarmism only clouds judgment, unnerves the public, and makes a hard job harder.

The NSA should have every lawful tool it needs to protect the country. And its vital work deserves a lot of leeway. But that’s all the more reason for congress to resist hysteria — and be open to reasonable change when it’s called for. — The Editors, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP