Twenty years after the genocide, Rwanda wants to become Africa’s hi-tech hub. Hundreds of thousands of schoolchildren already have their own computers and nearly the entire population is due to have Internet access within three years. But the government’s poor human rights record is casting a cloud over its ambitions.

Vanina Umutako, a student at Gashora Girls’ Academy in Rwanda, is proud of the app she and fellow students have designed.

“It will provide an interactive platform to facilitate connections between students from different schools and on different matters. They can quickly and easily discuss topics taught in class,” the 18-year-old explains.

The 270 students at the science and technology model academy east of Kigali “will graduate as inspired young leaders filled with confidence, a love of learning, a sense of economic empowerment”, the school promises on its website.

That is an image very different from that of the central-eastern African country 20 years ago, when a genocide organised by Hutu radicals killed about 800 000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus in one of the biggest cases of systematic mass murder in modern history.

Rwanda became synonymous with genocide, mindless violence, ethnic hatred and masses of refugees.

Now the country is seeking to put that behind it, with hopes of becoming a key economic hub.

“Rwanda is the Silicon Valley of Africa,” says Aphrodice Mutangana, a young mobile technology entrepreneur who launched an app allowing people to donate money to elderly genocide survivors living in poverty.

The government is investing in education and in high technology in particular to speed the transformation of the largely agriculture-based economy into a service-based one. The effort is also designed to eradicate the ignorance and ethnic prejudice that are seen as having contributed to the genocide.

“With new technologies … we can really promote peace,” information and communication technology minister Jean Philbert Nsengimana said.

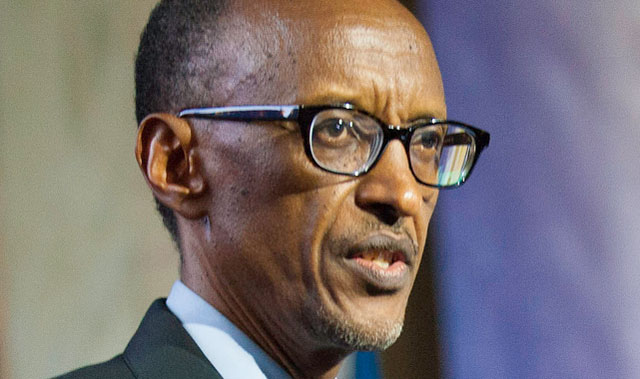

“We have one of Africa’s most ambitious IT programmes,” says President Paul Kagame, the African leader with the most Twitter followers, whom the International Telecommunication Union dubbed “the digital president”.

The government has invested more than US$100 in broadband Internet since 2010, providing Wi-Fi coverage to schools, public buildings, hotels, bus stations and markets in Kigali.

Last year, it signed a deal with South Korea’s KT Corp to roll out high-speed 4G Internet to nearly all its citizens by 2017.

The government has also distributed more than 200 000 laptops in about 400 schools across the country, where more than 70% of children complete primary school, up from 53% in 2008.

The Kigali Institute of Technology churns out nearly 20 000 graduates annually, while about 500 Rwandans travel every year to study IT and engineering in India.

The Carnegie Mellon University has opened a campus to teach IT and engineering in Kigali, making it the first US research institution offering degrees in Africa with an in-country presence, according to its website.

“Until 1997, there wasn’t even a mobile phone operator” in Rwanda, Mutangana said. “Now 63% of the population possess mobile phones and we have three private [operating] companies.

“The government is encouraging young people to start their own businesses. If you have an idea and you work hard, you make it here,” he added.

The World Bank ranked Rwanda as the easiest place to do business in sub-Saharan Africa in 2014, and Transparency International says Rwanda is the least corrupt country on the continent after Botswana, Cape Verde and the Seychelles.

Yet Rwanda has attracted little foreign investment due to factors such as insufficient infrastructure and a small domestic market.

The government’s plans of creating a large and high-tech-savvy middle class stand in contrast to the lives of the vast majority of Rwandans, who eke a living out of subsistence farming. About 40% of the population are classified as poor by the World Bank.

The economy has grown at an average of about 8% since 2001, but the growth was largely driven by high levels of public investment supported by aid flows.

Donors pour more than a billion dollars annually into Rwanda out of guilt over not having prevented the genocide and out of satisfaction with Kagame’s pro-business and anti-corruption policies.

But the US and other donors are now growing increasingly critical of the lack of freedoms in the country where dozens of alleged government opponents have disappeared this year.

The rights groups Human Rights Watch says some of them later turned up in court while others were found to have been murdered.

In July, internal security minister Sheikh Musa Fazil Harelimana admitted that security organs were holding 44 people who went missing, The East African reported.

The threat of aid cuts underscores the need for Rwanda to become less dependent on aid and strengthens the government’s determination to turn the country into a hi-tech hub.

“We want to turn Rwanda into an information society and the government is determined to achieve this,” Nsengimana said. — Sapa-dpa