The writers who craft songs for artists from Garth Brooks to Beyonce plan to tell a panel of US judges this week that the increasing popularity of music streaming services like Spotify will destroy their profession unless they get more royalties.

In a hearing scheduled to begin on Wednesday, songwriters and the organisations representing them will try to persuade three federal judges on the Copyright Royalty Board in Washington to adopt a new standard that could earn songwriters a higher rate from streaming. Google, Amazon.com, Apple, Pandora Media and Spotify are countering with their own proposals.

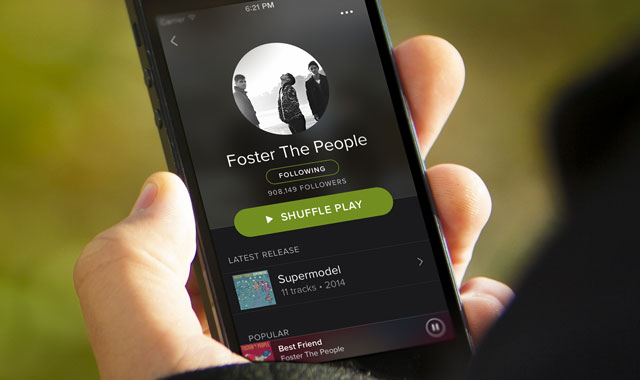

On-demand streaming has boosted overall industry sales two years in a row, surpassing iTunes and physical CDs as the largest source of revenue for the music industry. Songwriters say the shift has cut their pay and see the hearing as their best chance to propose a palatable status quo. Whatever rate the court picks will last five years.

Under the current model, streaming services give songwriters the greatest number of three possible outcomes — all of which amount to a share of revenue generated by the services. Songwriters want to add a per-stream rate to protect them from a number of changes in the industry that could limit their share of future sales in the industry’s fastest growing sector.

“We should get compensated every time someone streams a song,” said David Israelite, CEO officer of the National Music Publishing Association, a trade organisation. “The structure is a complicated formula that’s about percentages of revenue, and we don’t think that works well for us, or that it’s fair to songwriters.”

It’s a familiar refrain. The music industry has been fighting Internet companies in court and public for almost 20 years. While record labels’ sales have grown recently, they still have a long way to go to recover from listeners’ shift from CDs to pirated songs, singles from iTunes and free videos on YouTube.

All five streaming companies tout how much money they already pay back to musicians, and blame gatekeepers — record labels, music publishers and others — for keeping too much of the money. Apple has proposed a per-streaming royalty rate, but the songwriters say it’s too low.

Neither Spotify nor Pandora is profitable, and both companies argue that they already give away more than they can afford. Spotify, the largest of the music streaming services, has been contemplating an initial public offering, but questions have lingered about its ability to make money eventually.

Google declined to comment on the hearing in Washington. Spokesmen for the other companies didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The business of songwriting and publishing is over unless they change the way we get paid

Awarding royalties for songwriters is a byzantine process. While record labels can negotiate with Spotify on the open market, songwriters’ rates in the US are subject to government regulation due to a law written in the era of the player piano. Some publishers, which represent songwriters and administer their royalties, already have their own deals with the streaming companies, but the hearing this week gives them a chance to set a new bar for the arrangements.

While recording artists have turned to touring to make up for lost CD sales, songwriters have no similar recourse. The number of composers working in Nashville has shrunk to less than 400 today from around 3 500 about 13 years ago, according to Lee Thomas Miller, one of the songwriters who may testify at the hearing.

“Spotify or Pandora will play a song millions and millions of times, and those are worth $10,” said Miller, who has written hits performed by country stars Garth Brooks, Tim McGraw and Brad Paisley. “The business of songwriting and publishing is over unless they change the way we get paid.”

Battle averted

Songwriters and online services avoided a drawn-out legal fight five years ago — the last time the rates were reviewed. Then, most of the major streaming services were either small or nonexistent, and the framework for those deals was based on projections for a business that didn’t yet exist.

Paid streaming services have since ballooned. More than 100m people around the world pay for a service of some kind, with Spotify and Apple Music attracting the lion’s share of customers.

On-demand streaming services make the majority of their money from paying subscribers, and some, such as Apple, don’t offer any free on-demand music. But the majority of music listening still occurs on free, advertising-supported services offered by YouTube and Spotify. Spotify generates a small fraction of its overall revenue from free customers, and songwriters would like a bigger portion of those proceeds, too.

Amazon gives its streaming services for free to customers of its Prime delivery service, and publishers anticipate that other companies, such as mobile providers, will offer music as a free enticement for their packages. That could undercut their share of sales.

Publishers also expect that the growth in paying subscribers will slow even as consumption keeps growing.

“You have these giant companies using music to drive economics of other things about their business,” Israelite said. “Because of that, we’re likely to have a big war over how much they should pay songwriters to do things they do.” — (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP