By the heady standards of Alfred Hitchcock, his 1958 film Vertigo was a failure. It only just broke even at the box office at a time when the director’s films where raking in money. It received a lukewarm reception from the critics, who sniffed that it was “only a murder mystery” not worthy of two hours of screen time. Those same critics must be today choking on their words or spinning in their graves.

After decades of critical reevaluation, Vertigo has come as close to official recognition as the greatest film of all time as a film gets by topping arguably the most important annual poll of critics and movie academics. In the British Film Institute’s Greatest Films survey for 2012 — Chicago Times critic Roger Ebert calls it the only poll “serious movie people take seriously” — Vertigo unseated the Orson Welles masterpiece Citizen Kane from a spot it held for five decades.

It’s not the major upset that it appears to be, even if Kane appeared ossified into the position of Greatest Film Ever. Vertigo has steadily climbed the rankings since 1982 and only five votes separated the films in the 2011 poll. Perhaps Vertigo isn’t as important a milestone in movie history as Kane — now at number two — or Renoir’s The Rules of the Game at number four, but it is a film with an emotional texture that makes it easier to love.

I’m not convinced that it’s the best film of all time or even Hitchcock’s best movie, but it is one of the best psychological thrillers of all time, a film that transcends its genre and one that remains deeply intriguing after repeat viewings. Six decades after its release, Vertigo remains as entertaining as any of Hitchcock’s best films and for many of the same reasons.

There’s the vivid travelogue imagery of San Francisco; the swirling menace and melancholy romance of Bernard Herrmann’s score; and the careful build-up of suspense. Vertigo was also technically innovative. It contributed the Vertigo Effect, created by zooming in with the lens while pulling back with the camera, to the language of the cinema.

But all that is not what give Vertigo its stature. As Martin Scorsese says of the film, the story also does not matter, since it’s a film about the characters. It is a “very, very beautiful, comfortable almost nightmarish obsession”, says Scorsese. It’s Hitchcock’s psychological acuity, his penetrating gaze into his characters, which give this film such startling power. For modern critics and auteur directors like Scorsese, it is the intensely personal feel and emotional resonance that make Vertigo so rewarding.

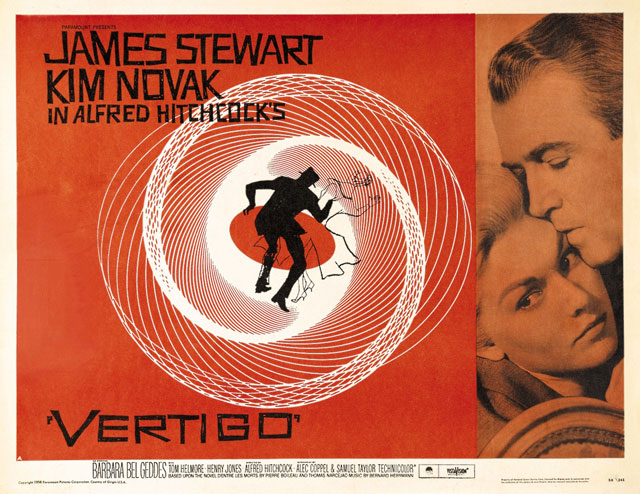

The film was based on a book by French writers Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, who incidentally also wrote the novel that inspired Les Diaboliques, the greatest film by the French Hitchcock, Henri-Georges Clouzot. The film is about the obsessive relationship that acrophobic cop Scottie (played by James Stewart) develops with blonde ice queen Madeline (Kim Novak) after a jealous husband hires him to tail her.

When she dies by plummeting from a bell tower, Scottie transfers his desire for Madeline to Judy, a doppelganger for the dead girl he meets by pure chance. Scottie starts to remake Judy into the image of the lost object of his desire with tragic results for both.

Vertigo is about the dark stuff of desire, deeply disquieting at its core with no need for shock twists or sensational acts of violence. In Francois Truffaut’s famous series of interviews with the British directors, Hitch explains with apparent relish that the film is about a man recreating the perfect sex image of a dead woman from another who is alive so that he can indulge in metaphorical necrophilia.

It’s Hitchcock’s most personal film, one which sees him wrestling with his ambivalent feelings about women, both the long list of icy blondes he directed in his films and famously mistreated behind the camera as well as the women in his personal life. Some see it as a lament for the loss of one of his favourite actresses, Grace Kelly, after she married into Monaco’s royal family.

But it’s made especially interesting by the fact, as Ebert writes in an incisive review, that “Judy … is the closest [Hitchcock] came to sympathising with the female victims of his plots”. She’s one of the most complex, richly realised female characters in a Hitchcock movie, fittingly in a film about the objectification of women by male desire.

Interestingly, many of the things that critics and audiences did not like at the time Vertigo was first released have turned out to be the elements that lift it above the average psychological thriller. Audiences hated having Stewart play a morally grey character with a nasty streak, but the matinee idol shines as a man who will sacrifice his decency to his desires. Hitch blamed Stewart’s age — double Novak’s 24 years — for the film’s poor commercial reception and never used the actor again.

And Novak, criticised then for wooden acting, is nothing short of remarkable. Ebert again: “Novak, criticised at the time for playing the character too stiffly, has made the correct acting choices: ask yourself how you would move and speak if you were in unbearable pain, and then look again at Judy.”

The film was criticised for revealing its twist with an hour of running time ahead of it. This was a decision that Hitchcock made because he wanted the suspense to come from viewers wondering how Scottie would react when he found out something they already knew.

The film isn’t about what will happen to Scottie, but what he will do in response. We have come accustomed to contrived twists piled on top of each other in thrillers today, so it’s gratifying to encounter one that remembers about the “psychological” part of the equation.

Some complained that the film doesn’t tie off the loose ends as carefully as Hitchcock’s other films, but the untidiness seems appropriate. It leaves questions hanging in the air that can’t be answered despite the reams of commentary Vertigo has inspired over the past 60 years. — (c) 2012 NewsCentral Media

- Read more: The British Film Institute’s 50 greatest films of all time

- Read more: The Hollywood Reporter’s take on Vertigo’s dethroning of Citizen Kane