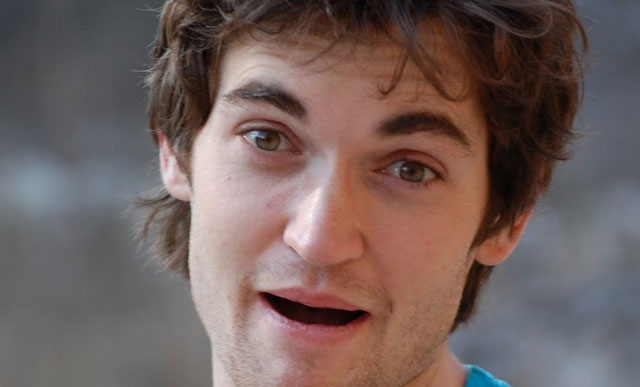

Newswires, forums and social media have been abuzz since Wednesday, when news broke that notorious online marketplace, the Silk Road, has been shut down and its alleged mastermind, Ross William Ulbricht, or “Dread Pirate Roberts”, arrested.

Newswires, forums and social media have been abuzz since Wednesday, when news broke that notorious online marketplace, the Silk Road, has been shut down and its alleged mastermind, Ross William Ulbricht, or “Dread Pirate Roberts”, arrested.

The Road, as patrons apparently affectionately called it, is no more, but others will follow in its footsteps. The effects — both good and bad — will be felt for years to come.

Only accessible using the anonymous Tor Web browser, the death of the Silk Road may go some way to rehabilitating public perception of the virtual, largely untraceable, cryptocurrency Bitcoin, whose existence Sil Road sullied. Bitcoin was the only method of payment used on the Silk Road, with international postal services or courier companies used to facilitate deliveries.

The Road wasn’t the first online marketplace for illegal goods and services; it was just the most successful. And where there’s fame, there are sure to be copycats.

Perhaps the most alarming implication of this week’s news is that the Tor network, used by journalists, activists and others for legitimate reasons — mainly privacy and anonymity — may be far less impenetrable and secure than we’ve been led to believe.

With the slew of revelations surrounding the scope of surveillance exercised by the National Security Agency in the US and its UK counterpart, the Government Communications Headquarters, online privacy is something we should all be concerned about.

The official line from Tor is that it was Ulbright’s carelessness outside of the Tor network that allowed the FBI to bring him to book, but if that isn’t the case, it’s certainly not in the authorities’ interests to let on.

That’s a far more alarming prospect than people buying drugs online.

Reports do indicate a series of missteps, including Ulbright’s using his real name on a programmers’ forum, were instrumental in his undoing, and will doubtless be pored over by would-be imitators. But there’s no doubt the FBI and other law enforcement agencies have been looking at ways to track those using Tor for illicit purposes. Their success would be bad for anyone who values digital privacy — and everyone ought to.

Much of the hoopla surrounding Ulbright and the Road also ignores the value it offered to consumers and the public interest it generated in Bitcoin, and cryptocurrencies more generally.

Cryptocurrencies aren’t going to go away anytime soon — in fact, more spring up all the time as their creators hope to emulate Bitcoin’s success and as individuals burnt by the gambles of rogue investors, poor credit policies and the resultant global economic downturn look for alternative stores of value.

What also won’t go away, of course, is people’s desire for recreational drugs. The so-called “war on drugs” continues to show itself to be zero-sum game. As prohibition demonstrated, where there’s demand, someone will seek to supply, and where the prohibition is sanctioned by those in power, most often it’s organised crime that steps in to meet demand.

Drugs are simply too sought after and too lucrative a commodity to be stamped out. Often called the eBay of drugs, the Silk Road’s success was linked to the same peer-review mechanisms that have made other digital marketplaces work so well. Peer review helps keep merchants (and buyers) honest.

The drug trade could benefit greatly from those mechanisms because, ultimately, selling drugs is still a business. The difference, however, is that it’s one that traditionally has offered consumers very few protections or guarantees.

Just as needle programmes reduce instances of hepatitis and HIV by preventing intravenous drug users from engaging in risky behaviour like needle sharing, there’s value in drug users knowing what they’re taking. The Road offered buyers reviews not only of the sellers but also their wares. Most of the most popular items had user comments that included lab reports on purity and composition. Try getting that sort of detail in Hillbrow.

Of course, drugs are a tough sell for any government, and in the Road’s case it’s all the more difficult to defend because governments are naturally suspicious of a currency that undermines the fiat currencies. Then there’s the problem of the brazen use of the world’s postal systems by drug dealers to deliver their goods, not to mention the other alarming services the Road offered.

It’s tough to see the Road as a supporter of small business and cottage industries in the way a service like Etsy is, and governments had legitimate reasons for wanting to shut it down. But anyone who thinks these sorts of services are going to vanish, despite the risks, is mistaken. — © 2013 NewsCentral Media

- Craig Wilson is deputy editor at TechCentral