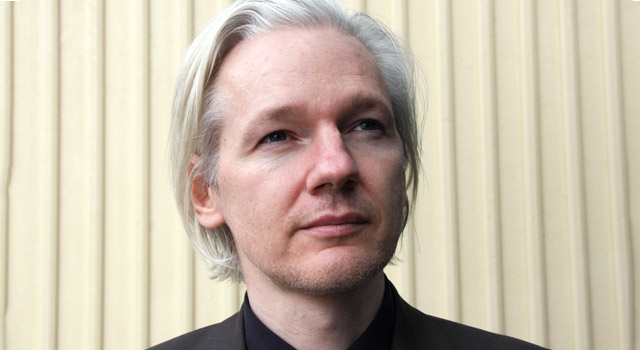

Since the last time we were together inside his prison lodgings at the Ecuadorian embassy in London, a few things have changed. Julian Assange has grown a beard, looks more pallid and pauses when I ask after his general health.

His legal team are warning that the shadows of detention without charge are now taking their toll. The caution is not just legal jousting: for more than a thousand days, locked down in cramped space that is nowhere, the pale rebel with a fearless grin has not lived a normal life.

Surrounded by armed police and invisible spies, he enjoys no safe spaces for exercise. There are no strolls through streets with friends, no sunlight on his face, no fresh air inside his lungs, and no access to adequate medical facilities. Physical confinement and round-the-clock deep surveillance are his fate.

Some things haven’t changed: the intense eyes, the furrowed brow, the intelligence and unalloyed courage. And the conviction that he continues to be punished for doing what he had to do, for following to the letter Kafka’s advice: when the earth grows cold and people everywhere fall asleep, blanketed in the darkness of innocent self-deception, someone has to brandish a burning stick, someone must be there, someone must keep watch.

Some say that the watchman is fast becoming a forgotten hero of resistance to state secrecy, or that in publicity terms he doesn’t measure up to the straight-laced liberal American genius of Edward Snowden. None of this is true.

Julian Assange was instrumental in arranging Snowden’s great escape from the US to Russia. The pluck of WikiLeaks meanwhile keeps its founder in the world’s headlines. So does ongoing media coverage of his legal fight against confinement and extradition. Detention hasn’t damaged his reputation for daring, or shattered his will.

He reads much more than before. And he’s eager to engage with big and challenging ideas, and to come up with his own, as I soon discover when we sit down at a small table to run through themes raised in his new book, When Google Met WikiLeaks.

“Google pretends it isn’t a company,” says Assange. “The world’s biggest and most dynamic media conglomerate portrays itself as playful and humane. But Google is not what it seems. It’s a deeply political operation. We must pay attention to how it operates, and prepare to defend ourselves against its seductive powers of surveillance and control.”

Assange is sure Google is a political matter, yet right from the beginning of our conversation I note his fascination with the question of why its global public reputation rides so high. I press Assange to explain why many millions of people around the world think of Google as a synonym for state-of-the-art technical progress. Assange recalls the forgotten fact that the company founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, dubbed their first-cut search engine “BackRub”. It was a college-level call to engage with the Web’s “back links” and (presumably) a freshman joke and people-friendly marketing ploy. Later the logo morphed into google.com (from “googolplex” and “googol”, referring to specific very large numbers). The seductive imagery stuck, to the point where everything now seems to work in the company’s favour.

Google, says Assange, “advertises itself as a great liberating force in the world”. It’s not just that Google has become a new verb in many languages, or that it has headlined the word “search”. The company cuts a swagger. Google is all good things to everybody.

“We’ve come a long way from the dorm room and the garage,” says its website. Yes, it has. Overseen from its Googleplex headquarters in Mountain View, California, the company has more than 70 offices in more than 40 countries with “murals and decorations expressing local personality; Googlers sharing cubes, yurts and “huddles”; videogames, pool tables and pianos; cafes and “microkitchens” stocked with healthy food; and good old fashioned whiteboards for spur-of-the-moment brainstorming”.

Google knows it’s a carrier of cool, says Assange. “In less than a quarter of a second, users who google ‘Google’ in English are greeted by 7,3bn results, one for each person living on our planet.” His point is that Google is more than just a company. It prides itself on being a force for good. Google says it gives back to the community. It wants “to make the world a better place”. Google is restless. It is hypermodern. It is visionary. Google is the future.

Digital colonialism

When Google Met WikiLeaks is an effort to humble power by unpicking the social licence forged by Google. “Unlike Shell or Unilever, it appears not to be a corporation,” Assange explains. “It cloaks itself in beneficence, the impenetrable banality of ‘Don’t be evil’.”

With help from Hannah Arendt, the gist of his attack is that Google hypocritically mucks with the murky world of high-level power politics. Assange speaks of “digital colonialism”. It’s his shorthand way of noting that our digital age has spawned a new type of state-backed corporation with a “missionary” mentality, a form of tutelary power that spreads itself across the planet, into the daily lives of many millions of people, in the name of “doing good”.

I ask Assange whether he thinks Google is becoming a 21st-century version of the Honourable East India Company. At its peak, the English joint-stock company accounted for half the world’s trade, dominated such commodities as silk, salt, cotton, tea and opium, and ruled large areas of India with its own private armies and administrative apparatus.

“It’s worse than the East India Company,” he replies. “From memory, the company ruled according to a royal charter, but the government owned no company shares and had limited control over its activities, which were backed by a huge standing army. Google’s different. It’s trying to keep quiet about its actual politics. It’s in a state of public denial about its global ambitions, and its deep entanglement and collaboration with the American government.”

So the charge is that “liberty loving” Google secretly sails with the navy, not the pirates. Google, Assange says, is now a master of “back-channel diplomacy for Washington”. When Google Met WikiLeaks details the many ways the corporate communications giant shapes decisions and non-decisions in the political scene.

“Three years ago, Google finally joined the ranks of top-spending Washington lobbyists,” Assange tells me. “It’s a list usually stalked by such giants as the US Chamber of Commerce, military contractors, and the petro-carbon leviathans. Google is now at the top of the company list.” It annually spends more on lobbying than military aerospace giants Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and Boeing.

Assange is a world-class muckraker skilled at tracking down connections and culprits. The book is built around painstaking research into the links that publicly implicate Google in the highest circles of the American state. He lays into characters like Jared Cohen, who in 2010 moved from the US state department, where he had been senior adviser to secretaries of state Condoleezza Rice and Hillary Clinton, to head up the “think/do tank” Google Ideas.

Assange is especially critical of Eric Schmidt, who served as Google’s CEO from 2001 to 2011 and is now its executive chairman. Assange spent time with Schmidt in mid-2011 and describes him as part of the “Washington establishment nexus”. Now tacitly backing Hillary Clinton’s bid for the presidency, Schmidt pays regular visits to the White House and delivers “fireside chats” at the World Economic Forum in Davos. He likes the “pomp and ceremony of state visits across geopolitical fault lines”. Assange dubs him “Google’s foreign minister”, a “Henry Kissinger-like figure whose job it is to go out and meet with foreign leaders and their opponents and position Google in the world”.

Schmidt has reacted bitterly to these charges. “Julian is very paranoid about things,” he told the American ABC News last year. “He’s of course writing from … the luxury lodgings of the local embassy in London.” Then came the blanket denial: “Google never collaborated with the NSA [National Security Agency], and in fact we’ve fought very hard against what they did.” Wagging his finger, he added, “We have taken all our data, all of our exchanges, and we’ve fully encrypted them so no one can get them, especially the government.”

Assange looks annoyed when I quote these words back to him. It’s not just the raspberry reference to “luxury lodgings” at the Ecuadorian embassy or the personal dig. What really irks Assange is the denial by Schmidt and Google staff of their political connections and the “revolving door” relations between Google and the US government. “Google’s bosses genuinely believe in the civilising power of multinational corporations, and they see this mission as supportive of the shaping of the world by the ‘benevolent superpower’.”

Google, a flag-bearer of the new Californian “free market” ideology of digital capitalism, is an accomplice of the American state, Assange insists. He reminds me that early Google search technology was seed-funded by the NSA and CIA “information superiority” programmes. Since then, the family integration of Google and the government has tightened. Assange rattles off a string of cases. Each runs well beyond the politics of personal connections, and each connection is damaging to Eric Schmidt’s claim that Google has clean political hands.

Assange says that in 2004, after acquiring Keyhole, a mapping tech start-up co-funded by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and the CIA, Google integrated the technology into Google Maps, an enterprise version of which has since been shopped through multimillion dollar contracts to the Pentagon and linked-in federal and state agencies.

Four years later, Google helped launch into space an NGA spy satellite, the GeoEye-1. Google shares its photographs with the US military and intelligence communities. In 2010, the NGA awarded Google a handsome contract for “geospatial visualization services”. In the same year, after the Chinese government was accused of hacking Google, the corporation agreed to a “formal information-sharing” partnership with the NSA, which was said to allow NSA analysts to “evaluate vulnerabilities” in Google’s hardware and software. Although details of the deal have never been made public, Assange says the NSA brought in other government agencies, including the FBI and the department of homeland security, to help.

Google has meanwhile become involved in a programme known as the Enduring Security Framework (ESF). It shares information “at network speed” between Silicon Valley tech companies and Pentagon-affiliated agencies. It’s a chummy relationship, Assange tells me. E-mails published by WikiLeaks in 2014 after freedom of information requests show Eric Schmidt and Sergey Brin corresponding on first-name terms with NSA chief General Keith Alexander about ESF.

Then, says Assange, there are the Prism programme files released in mid-2013 by Snowden. They show that Google, in clear violation of guidelines issued by the US Federal Trade Commission, covertly provided the US intelligence machine with access to petabytes of personal data. They show as well that Google has accepted NSA funding (to the tune of several million dollars) to furnish the agency with search tools for handling its “rapidly accreting hoard of stolen knowledge”.

Moonshot thinking

On the very afternoon I’m with Julian Assange, as if to hammer home the gravity of the point he’s making, a jarring message arrives from Google’s lawyers. It confirms what he’d always expected: throughout his time in detention, the company that does no evil has been trying to leech every drop of personal account information about Assange and his WikiLeaks team, and has been passing it through the NSA to the FBI.

WikiLeaks encrypts all of its internal communications with meticulous care, but since my appointment with Assange was arranged by his staff through outside channels, I’m no doubt implicated in the breaking news. It’s my crash-test dummy moment: a body shock, a highly personal reminder of the growing dangers of give-us-everything government surveillance, the political epiphany when suddenly my Web browser, my credit card, and my phone calls and messages change significance. I feel violated, as if by a faceless thief who now knows tomorrow’s plans, today’s gripes, my quips and jokes, my likes and dislikes, who I hang out with, perhaps even my deepest desires.

The watchman continues, in defiantly low tones. “Nobody wants to acknowledge that Google has grown big and bad,” Assange says. “But it has.” The comment underscores his radical willingness to take on the corporate world, in ways that are glossed over or outright ignored by cultural romantics and conservative critics of “technology” (Nicholas Carr, Jaron Lanier and Andrew Keen are examples) and by “liberal” critics of state snooping on individuals. Our misfortune is not “technology” or state surveillance alone, he is saying. We’re drifting towards a networked world of “total surveillance” marked by the data-driven, will-to-control marriage of big governments and big corporations.

Assange likes a feisty quibble, so as mugs of tea arrive on our table I switch to devil’s advocate. “Why are you so dismissive of the grand technical progress made by Google?” I ask. The plain fact is that in many people’s minds Google isn’t simply (I use Marx’s words) a hideous heathen god who drinks nectar from the skulls of its victims. Google’s market success and magnetism stem not just from clever PR, gimmicky animated Google Doodles on its homepage, the “free” tools it gives to users, or what Assange refers to in his book as “an enticing service that harvests information that people are not fully aware of”.

Isn’t the high-flyer reputation of Google much more to do with the fact that its growth from a Silicon Valley start-up to a global company with annual revenue of US$55bn has made it a technology leader? Isn’t there truth in the claim of its co-founder and CEO Larry Page that the company fosters “moonshot thinking” and places “big bets on the future”? Isn’t technical innovation the fruit of the company’s bullish strategy, backed by Google Ventures and Google Capital, of acquiring start-ups, setting up freestanding business units and promoting “bottom-up” management, in which young company wizards are permitted to spend 20% of their time working on projects of their choosing?

Assange lets the contrarian carry on. I remind him that economists emphasise how, in this emerging second machine age, giant businesses like Google are necessary for innovation, which is both the core of effective competition and the powerful lever that in the long run expands output and brings down prices. There’s room for objections, sure. Monopoly can be a spoiler of innovation. And, yes, there’s the ethical objection that Google is behaving just as badly as Bell’s telephone company did in its struggle against Western Union, the outfit that had dominated the old telegraph industry. Google is indeed the new face of predatory capitalism. It’s brigandage, led by hucksters willing to take big risks for money and power. And yet Google’s technical achievements are nothing less than stupendous.

Assange continues to sit in silence as I gallop through a list of Google’s triumphs. Under the do-good banner of making “the world’s information … universally accessible and useful”, Google launched a dot-com enterprise in the search business. While based at Stanford University, it made a copy of the entire World Wide Web and pioneered, patented and deployed an indexing system based on a secret-sauce probability-based algorithm called PageRank. It radically improved the signposting of the Internet by reorganising online connections and content, not through conventional modes of cataloguing, such as alphabetical listing, but by assigning pages a “popularity ranking” based on their volume of links with other high-ranking pages.

The PageRank system had a “democratic” feel and took off commercially, big time. The invention lured venture capitalists and huge advertising revenues and enabled Google to grow faster than any other large firm in the communications industry.

Processing more than a billion search requests and 25 petabytes of user-generated data each day, the company’s market share of the online search business burgeoned. Google turned itself into an advertising machine that by 2010 had earned more money from search-based advertising than the entire newspaper business in the US. This allowed it to launch a chain of products, triggered acquisitions and built business partnerships beyond its core Web search business.

Emphasising a future in which easy access to information could become a reality for all users across fields as diverse as telephony, newspapers, video, film and television, Google acquired Keyhole’s EarthViewer 3D program (now Google Earth) and YouTube. It championed a capacious free-of-charge Gmail service, an instant messaging application, a translation service, and the highly successful Android mobile operating system.

It alerted users to traffic jams or coming meetings through Google Now; launched a video chat facility called Google Hangouts; and developed Google Glass, wearable augmented reality glasses connected to the Internet through Wi-Fi or Bluetooth. It began to build an online library.

The company set up Google News, an aggregator of the world’s news services. Google Fiber provides a bullet-speed broadband service. Google entered the mobile telephone business (with the acquisition of Motorola and its patents in August 2011).

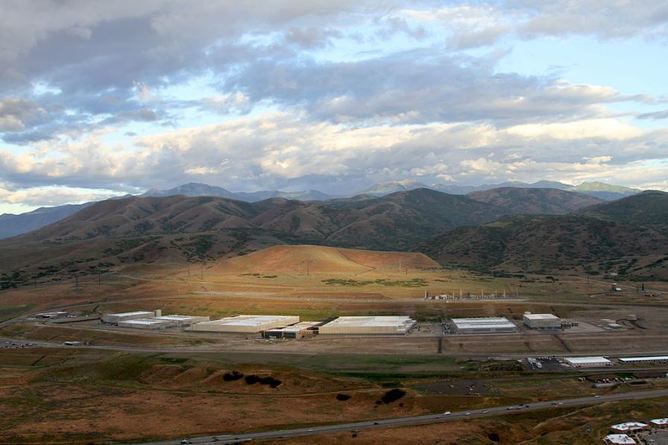

It launched a satellite, invested in renewable-energy projects and assembled a worldwide network of custom-built server farms, giant hangar-like information storage buildings equipped with power generators, cooling towers and thermal storage tanks.

Now there’s Project Loon, designed to beam Internet access down to the most remote parts of the planet, using specially equipped balloons that kiss the upper edges of the Earth’s atmosphere.

It has launched the Quantum Artificial Intelligence Lab, a facility for developing quantum computers targeted at businesses and governments alike. Google is reportedly working on a version of Android for virtual-reality headsets.

It now has a substantial presence in Mountain View, where last year it signed a deal for its very own airport just east of the Googleplex, complete with a blimp hangar large enough to house the Hindenburg. Google is also on a hometown real estate binge, with recently released plans to build a new glass utopia of greenhouse-canopy offices in Mountain View.

Google in our heads

“All that’s true,” says Assange. “Google’s appetite for expansion is insatiable. But let’s add that Google obeys the Russian rule: get rich, get even, get legal! Google is not as innovative as most people imagine. It innovates through aggressive acquisition, then integrates what it has acquired. The bigger it gets, the faster it grows. It has built a massive global infrastructure of data centres. Its Android operating system is used by 80% of phones now sold. Google has already bought eight drone companies, and is now buying more. It’s deploying robotic cars, running Internet service providers and working on a plan to create Google towns.”

Without warning, he shifts topic, to Google’s efforts to grab hold of its users. “Google’s colourful, playful logo is stamped on human retinas around 6bn times each day,” he says, with a faintly sarcastic smile. “That’s 2,2 trillion times a year — it’s an opportunity for respondent conditioning enjoyed by no other company in history.”

“Respondent conditioning” is a tricky phrase bearing echoes of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Pavlov’s experiments with salivating dogs. Assange means something different. By invoking the old phrase, he’s out to provoke, in new ways. He wants to say that a communication giant like Google should not be thought of as a political leviathan brandishing a sharp corporate sword high over the heads of its subjects. It’s not an alien Dalek coming to get us. Google operates differently. It snuggles up close to its subjects. It wants to be our intimate acquaintance. It wields tremendous seduction power. It gets under our skin and inside our heads. It reshapes our senses and helps define how we see the world, and who we are. The really disturbing thing about Google, Assange contends, is that its manipulative powers are not understandable in conventional terms. We’ve never seen anything like it before, and for that reason alone he rejects the headline-grabbing claims of Maryanne Wolf, Nicholas Carr and others that Google is making us stupid because it is pushing us from an age of narrative intelligence into a society structured by data-driven perception.

“The issue is not the replacement of our capacity for complex inner reflection by a new kind of self that evolves under the pressure of information overload and technologies of the ‘instantly available’,” says Assange. “Those who say we’re becoming mere decoders of ‘information’, that we’re losing our ability to read and interpret texts deeply, without distraction, are misleading us. Aside from the fact that decoding information is becoming a vital public skill, there’s something else going on. It’s more politically complicated, more subtle and more threatening of our freedoms. We should wake up.”

Assange understandably rejects the pre-political flavour of grandiose claims about the end of narrative intelligence. He’s suspicious as well of populist literary attacks on Google. I talk to him about Germany’s Manfred Spitzer, a leading neuroscientist who pelts Google and the rest of the Internet with the charge that it’s spreading “digital dementia” caused by “addictive” products and processes that outsource human brain power, destroy our nerve cells, and, in both young and old people alike, result in such symptoms as reading and attention disorders, anxiety and apathy, insomnia and depression, obesity and violence.

Assange says this line of thinking is “not especially interesting. It could well be bullshit.” He again insists “there’s something else going on” and that “we should pay attention to its novelty”.

We reach the point in our conversation where Assange becomes most eloquent, most defiant, and strangely despondent. He explains he’s not simply trying to raise a red flag against Google’s fat-cat corporate power. The problem is not straightforwardly that Google is an emerging private digital monopoly whose aggressive market tactics openly contradict the public principles and practice of popular self-government. Assange agrees that the company’s professed commitment to democratic virtues is undermined by its arrogant culture of corporate secrecy. People find that out first-hand when they visit its California headquarters: after they hit reception, if they refuse to sign a nondisclosure agreement, then their access is heavily restricted. Even Google shareholders have grown uppity about the iron veil of secrecy that shrouds the company’s investment strategy. The secrecy associated with Google’s market power is certainly problematic. It contradicts the public spirit and substance of democracy, says Assange. But it isn’t the fundamental problem.

Assange is sure the public/private formulation that once informed the politics of social democracy is now old-fashioned, out of step with the new reality of Google as a mode of seductive power. “Google is an emerging state within a state. It’s a type of private National Security Agency,” he says. “It’s in the business of collecting as much data around the world as possible, about as many people and places as it can. It stores and indexes this data, builds profiles of people and sells them to advertisers. Spying is its business model. But as the Edward Snowden revelations make clear, it’s also a target and ally of the National Security Agency.”

Algorithms

There’s something else that worries Assange about Google, and why the whole business model of the corporation is a deeply political matter. Google, he tells me, is now shaping “the generative rules” of the information that reaches many hundreds of millions of people in their daily lives. Just as the rules of any given grammar enable and constrain speakers when uttering sentences, so Google is shaping who we are. For all its talk of openness, pluralism and dynamic experimentation, the company is driven by strong power instincts, “the will to mess with our most intimate selves for the sake of hooking us on its power”.

We talk about Google’s search engine technology. Just as early decisions about the routing of telegraph cables determined the patterns of use of telegraphed messages for decades to come, so choices now being made by Google are defining choices for future generations. Google is shaping the “hidden plumbing” of information flows, and it’s doing so in the name of opening up the whole world’s horizons to the whole world. Google says its mission is to organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful. It seeks to develop “the perfect search engine”, which Larry Page once defined as something that “understands exactly what you mean and gives you back exactly what you want”. There are sad moments of real hubris in all this, as when Eric Schmidt told the Wall Street Journal that “most people don’t want Google to answer their questions. They want Google to tell them what they should be doing next.”

As I quote these words, Assange laughs coldly. Google’s search engine technology is the basis of its claims to universality, but the company doesn’t actually control the search markets of Russia, China and South Korea. “The encrypted digital space known as the ‘dark net’ also proves this Google boast is hot air,” he says. “The dark net currently bears the reputation of a space that is bad and mad and dangerous, a playground for arms traders, paedophiles and drug traders, but what’s important in principle about ‘dark’ networks is their reminder that there’s a basic limit on Google’s will to control the information world. Their encrypted content isn’t indexed by standard search engines, which is why searching the Internet on the surface Web is often compared to fishing on the surface of a lake, or maybe an ocean.”

So isn’t user resistance to Google “colonialism” through the dark net a reason for being hopeful, I ask. “The trouble is that although we don’t know the actual numbers of people who daily access the Internet by entering encrypted dark zones, it’s probably only a small percentage of the world’s population,” replies Assange. Hence his concern about Google’s manipulative secret algorithms.

He’s referring to the claim of Larry Page that the whole idea of an indexing system came to him in a dream, in which he woke up asking himself whether it would be possible to download and index the whole Web. “The dream came true, but with damaging consequences,” Assange tells me. “PageRank did more than replace existing search methods tied to supercomputers, such as AltaVista. It came up with a new, PC-friendly definition of ‘intelligent’ ranking that assigned each and every page a rank according to how many other highly ranked pages are linked to it.

“It allowed Google Search to develop content-targeted advertising. The innovation created channels for advertisers to access several billion online users and untold numbers of audio-visual, film and text websites built by others. Google became much more than a verb. Its customers became its products. It enticed millions of online users into a strange nether world of complex algorithms that most people know nothing of, or do not understand, or simply take for granted.”

Singularity

Assange has a point that shouldn’t be underplayed: digital algorithms do indeed powerfully prefigure what we as citizens can think, say or do. Algorithms are a form of automated reasoning. They’re step-by-step lists of well-defined instructions for calculating any given function in advance. Backed up by Google’s paid search advertising platform AdWords, algorithms serve as the foot messengers, drum and smoke signals, semaphores and telegraphs within our world of digital information flows. “They push us towards a life of consumption lived inside a well-policed Singapore shopping mall,” Assange quips.

His political point is that algorithms don’t fall from the sky. They don’t exist in a power vacuum. They are never politically “neutral”. Their design and operation enable companies like Google to “rig” the content of communications in their favour.

But that is not all. Leaning forward, clutching his tea mug, Assange insists there’s a much more insidious threat to the democratic freedoms we cherish. It’s the way Google is now merging its search engine technology with cutting-edge business plans to build the so-called “Internet of things”, a world in which people, animals and objects are connected by a wide variety of digital devices such as speech recognition and question-answering software, heart-monitoring implants, biochip transponders on farm animals, and automobiles with built-in sensors.

Assange explains why he’s deeply interested in and “horrified” by the company’s business acquisitions and digital adventures. “Google’s tone is triumphal,” he says. “The company is convinced it can harness unlimited computing power to create immortality in an artificial Silicon Valley heaven on Earth. It wants to be master of a universe controlled by infinite machine power.”

Assange arguably stretches the point for effect, but impressive is the way Google executives ooze confidence in their ability to transform and control the mentalities and habits of their users. Google’s head search engineer Amit Singhal says that when users hunt for information, “the more accurate the machine gets, the lazier the questions become”. It’s as if a beneficent new golem is being born of Google.

“The ultimate search engine is something as smart as people — or smarter,” Larry Page said in a widely publicised speech several years back. “For us, working on search is a way to work on artificial intelligence.” Sergey Brin similarly reported, to Newsweek in 2004, that “if you had all of the world’s information directly attached to your brain, or an artificial brain that was smarter than your brain, you’d be better off”.

But what exactly might Google’s titanic quest to transcend the human/machine divide mean in practice? Assange says that hints at what’s coming down the line are offered by Ray Kurzweil, director of engineering at Google, who predicts the day is nigh when human intelligence will be outstripped by computer intelligence, and the two merge in what he calls “Singularity”. It’s a “religious atheism cult” vision of everyday life mediated in every social space, at every instant, connected by embedded digital devices. “Singularity is the God of Google,” says Assange. “It’s an imagined future universe of pervasive connectivity, a world in which unlimited computing power, people, robots and things are conjoined, placed under surveillance and transformed into profitable advertising platforms carefully watched by governments and under the control of Google.”

Assange emphasises that when the man of “religious atheism” speaks of Singularity he’s not joking or being ironic. Kurzweil really does mean to include everything, the whole lot. The cars we drive are already cognitive devices, computers on wheels, so why not develop an automated Google car, for use as a “robo-taxi”? (Google recently invested in the taxi service Uber.) For the slightly less adventurous, there’s MIT Media Lab’s Google Latitude Doorbell: it chimes a tune when a family member is approaching the house or flat. The equality principle is honoured: each family member has their own distinctive tune. There’s Google Fit, which integrates data drawn from Android devices with fitness and health apps used by other companies; the Google-backed 23andMe, a consumer DNA testing service; and a new Google-backed bio-tech life-extension company called Calico, which is developing nano-pills and drugs designed to detect and deal with cancers, heart attacks and other diseases associated with old age.

In 2013 Google acquired Boston Dynamics, a small company that manufactures robots capable of outpacing Usain Bolt and regaining their balance after slipping on ice. The R&D program is shrouded in strict secrecy, leaving pundits to speculate that Google is either developing a robot that can pull up outside your dwelling in a driverless car and walk a package to your door or trying to perfect the first “social” robots, semi-autonomous machines that learn by imitation to help people inside their homes, or do such jobs as issue parking infringements and street cleaning. Meanwhile, Google Now will dig through your e-mail for bill reminders and create cards reminding you of upcoming payment dates. Google has told the US Securities and Exchange Commission that it hopes to offer advertisements and other content across multiple devices including “refrigerators, car dashboards, thermostats, glasses and watches, to name just a few possibilities”.

In future, no doubt, there’ll be a Google version of MIT Media Lab’s Facebook Coffee Table prototype, which tunes in to your conversations and displays photos from your Facebook page whenever they’re relevant to what is being discussed. There might be gigantic Google blimps that rival Raytheon’s JLENS (Joint Land Attack Cruise Missile Defence Elevated Netted Sensor System) airships that provide high-resolution 360-degree radar coverage and targeted long-distance information on cars, trucks and boats; and, for the comfort of seasoned globetrotters, perhaps even a Google equivalent of the British Airways in-flight blankets fitted with neurosensors, the kind that glow blue when passengers are feeling relaxed and red when they grow stressed.

What can be done?

Tea’s well finished. There’s a gentle knock at the door and a polite staffer tells us it’s soon time for the next appointment. In our few remaining minutes together I press Julian Assange on practicalities. I quote lines from his essay on the subject of how best to put the knife into secretive arbitrary power. “We must think beyond those who have gone before us,” he wrote, “and discover technological changes that embolden us with ways to act in which our forebears could not.” Regicide and assassination were once the preferred weapons of the opponents of conspiratorial power, he noted. Now that the communications revolution has “empowered conspirators with new means to conspire”, the task is to find brand new 21st-century ways of “throttling” the information systems that feed what he now calls “total surveillance power”.

So, in the case of Google, what exactly might this re-imagined opposition to arbitrary power imply in practice? How most effectively can its concentrated monopoly power be broken up, brought back to Earth with a bump? Can anything be done? Or is our situation so hopeless that it would be better instead to start packing our bags for hell?

“Yes, many things can be done, and must be done,” Assange replies. We discuss how the opponents of Google Book Search stalled the digital book business venture in the American courts. He recalls that Europe’s highest court has since ruled in favour of a “right to be forgotten” by Google; and he adds that it’s imperative that European regulators succeed in forcing the company to apply that ruling to its entire global search empire.

Public backing should be given to the European Commission’s ongoing investigation into Google’s “abuses of dominance” and the EU parliament’s consideration of a non-binding resolution that would split Google’s search engine operations from the rest of its business.

It’s right, too, that governments put an end to “double Irish” tax avoidance schemes, whereby, say, Google makes multibillion-dollar profits in the UK and transfers those annual profits to one of its Dublin offices, which then gets an invoice from its Bermuda subsidiary for “research and development” costs that equal the original profit.

Led by the distinguished international jurist Baltasar Garzón, Assange and his legal team have meanwhile shown how to wage a spirited fight against Google surveillance, Swedish intransigence, smear campaigns and the real threat of extradition to the US by working through such bodies as the UK supreme court, Sweden’s court of appeal and the United Nations working group on arbitrary detention.

The anarchist watchman knows that his immediate fate depends heavily on the politics that underpin what he dubs the “rule of law pantomime”. He’s supportive of cross-border initiatives that are demanding a new global covenant for protecting the Internet as a shared democratic space, available for use by all citizens of the world.

He also acknowledges the vital need for citizens to take things into their own hands. Public calls for Google to do good, not evil, are everywhere on the rise. Protesters are disrupting Google gatherings (as in San Francisco in June 2014, when an activist slipped through tight security to bring conference proceedings to a dramatic halt by accusing Google’s employees of working for “a totalitarian company that builds machines that kill people”).

Websites such as Focus on the User are highlighting the underhanded methods and “sweetheart deals” used by Google to stack search results in favour of its own products. Citizens are meanwhile taking public action to refuse Google’s destruction of privacy.

Encryption is “the ultimate form of non-violent direct action”, says Assange. Hence the importance of “CryptoParties”, whose aim is to spread awareness of tools such as Tor software that makes user location and browsing habits harder to track, public key encryption (PGP/GPG) and Off-the-Record Messaging. But in the end, laments Assange, none of these resistance strategies may succeed.

The watchman is about to spring a farewell surprise. “What we must grasp is the tendency of digital information systems to connive with concentrated power,” he says, voice lowering. “The case of Google shows that knowledge is power, it proves that we’re hurtling at high speed towards a world worse than those in the dystopias of Jack London and Yevgeny Zamyatin, or Aldous Huxley and George Orwell.”

Then down comes the heavy gauntlet. “I think it’s misguided to be looking to Google to help get us out of this mess.” He pauses. “In large part, Google has put us in this mess. The company’s business model is based on sucking private data out of us and turning it into a profit. So I do not think it’s wise to try to ‘reform’ something which, from first premises, is beyond reform.”

Where this testimonial leaves us isn’t clear. The remark feels dispiritingly anti-political. It’s perhaps Luddite, certainly at odds with his active support for strategies that practically aim to rein in gargantuan Google, in defence of the principle that digital networks and information are the common property of all people on Earth.

Julian Assange arguably understates the capacity of citizens to make good democratic use of some Google services — YouTube, for instance. He also probably exaggerates the extent to which Google has the upper hand in the unfinished communications revolution of our time. Google isn’t infallible. Facebook, China Mobile, Apple and Microsoft (and its new Cortana “intelligent personal assistant”) are among its cut-throat rivals.

Yet he’s sure that the highly political business of the most aggressive digital giant in the world is destroying the free spaces so necessary for questioning and resisting the evils of concentrated power. Assange doubts that periodic elections can change much. He knows from bitter experience that inherited procedures of judicial oversight are badly broken, and he’s generally miserable about the future of democracy.

“Shrouded in secrecy, swallowed up by complexity and scale, the world is hurtling towards a new transnational electro-dystopia,” he says. “Localisation doesn’t matter that much. The Chinese Internet model and the American giant server farms are proof of the dangerous fact that digital automation is inherently coupled with the efficiencies of integrated centralisation and control.”

With these gloomy watchwords, Julian Assange declares his hand as a political dystopian, a public thinker bent on prompting public awareness of the grave dangers settling on our world. Who can blame him for wanting to play the role of public opponent of digital prisons? He’s after all the citizen who’s trapped in detention. He’s met the enemy, and plumbed their deepest secrets.

Hence his attachment to cypherpunk, his warning that, since Google is living proof that the world can be seduced by forms of mass control that spark little or no resistance, there’s nothing left for the public thinker but to brandish a burning stick, to keep watch, to be there on the spot, eyes wide open, to sound the political alarm. ![]()

- John Keane is professor of politics at the University of Sydney

- This piece was originally published in The Monthly (June 2015). It is republished here from The Conversation