WhatsApp is the most popular messaging app in the world with over two billion monthly active users.

WhatsApp is the most popular messaging app in the world with over two billion monthly active users.

While the Meta Platforms-owned app dominates in many emerging markets, including South Africa, there are places where the default messaging app is something completely different.

South Koreans, for example, prefer to use homegrown KakaoTalk, while in North America and Australia, Facebook Messenger is the go-to communication app, and in Japan, it’s an app called Line.

Messenger, WhatsApp, Line and KakaoTalk did not always hold dominant positions in their respective markets. So, why is it that some messaging apps rise to dominant status – and what eventually causes their decline, only to be replaced by something else?

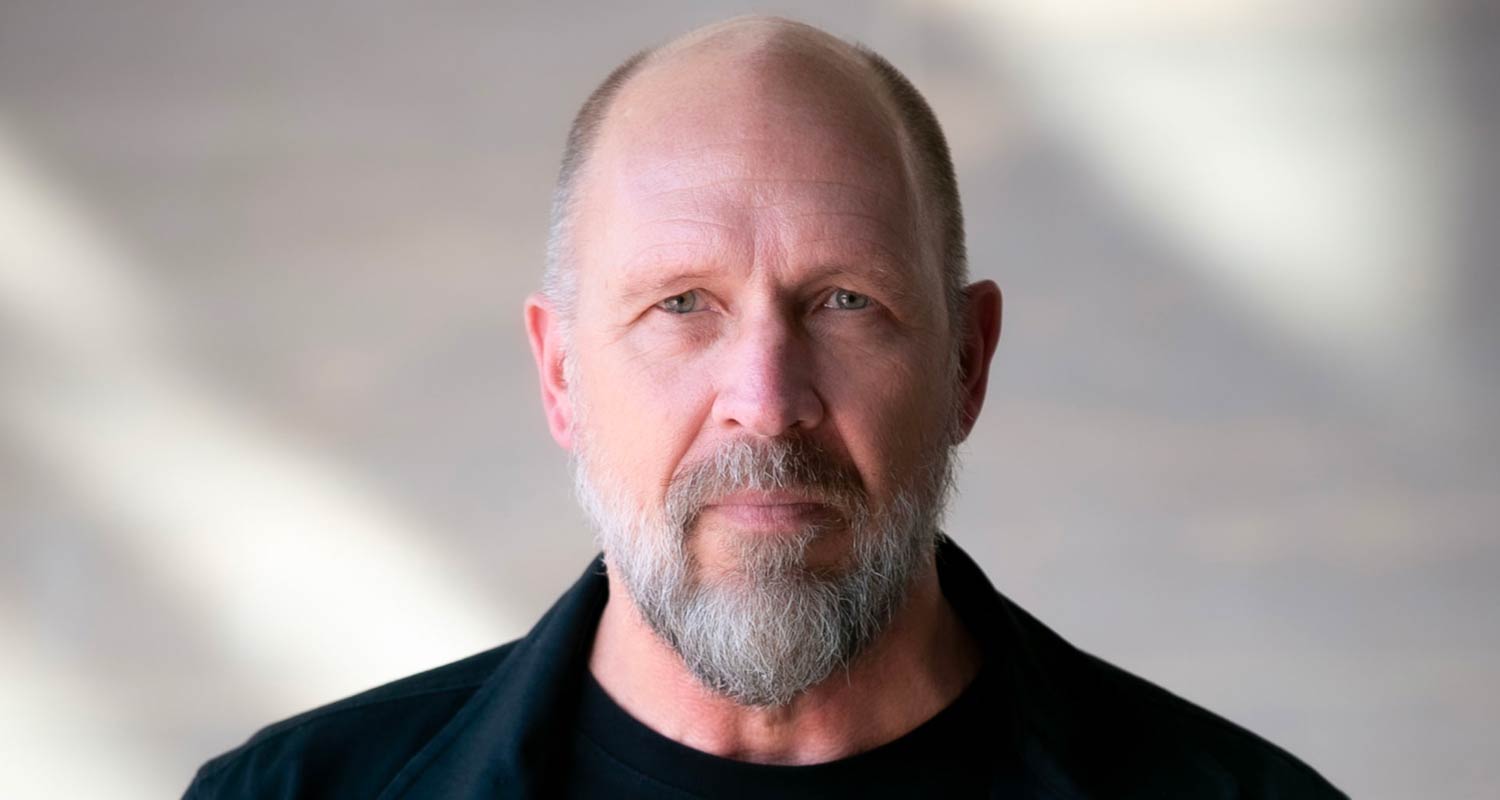

“One of the most valuable things any app can build is called the ‘network effect’,” Gour Lentell, founder and CEO of the data-free chat platform MoyaApp, said in an interview with TechCentral. “The only way you can disrupt a market incumbent with massive network effect is if you have a value proposition that is so much better or different.”

“Network effects” is a term coined by former Bell Telephone president Theodore Vail and describes marketplaces such as telephone networks, online classifieds and messaging apps where the value that a single user derives from the goods or service being provided increases with the number of other people using that utility. Network effects drive more people into the marketplace and increase the likelihood that they will stay there as well.

‘Platform of choice’

“I moved to South African from Australia five years ago. I can’t come here and say to everybody that I use Telegram and that is how I message; no one will talk to me. I will adapt to the platform of choice in a market because that is where everyone is,” Lentell said to illustrate the binding power of network effects.

In South Africa, Mxit was once “the platform of choice where everyone is”, only to be overtaken by BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) and eventually WhatsApp. Mxit certainly had network effects of its own for a while, along with a compelling value proposition since it made chatting cheaper.

Although BBM seemed like a strong contender for a while, BlackBerry’s insistence on device integration blinded the company to the potential that BBM had independent of Blackberry, Lentell said. BBM was not available on other platforms other than BlackBerry phones.

Read: WhatsApp adds 32-person voice calling feature

This hampered BBM’s value proposition by creating a barrier that excluded a large portion of the market. Lentell said BlackBerry’s device-first strategy worked while its devices were the most attractive to consumers. The arrival of Android changed that narrative.

“It was only years later [after the fall of BlackBerry] when someone said, ‘You know, if we’d just taken BBM out of BlackBerry devices and made it work on all devices, we could have won the game.’ They didn’t because they were focused on selling phones.”

WhatsApp then came along with a value proposition so compelling that it overcame any of the network effects that Mxit and BBM had amassed in the local market: a high-quality, asynchronous chat experience that is also cheap and accessible on any kind of device.

Mxit, as the incumbent, was in a position to provide this kind of chat platform to South Africans, so why did it fail?

“Mxit failed because we didn’t have a critical mass on smartphones,” former Mxit CEO Alan Knott-Craig said. Lentell’s opinion the matter adds some background to Knott-Craig’s assertion.

“Mxit failed because their smartphone app strategy didn’t really work. They did build a smartphone app but it was a bit clunky and it wasn’t a great experience. It worked but it was all a bit too much. Mxit had a slightly confusing product strategy because they were trying to do other things with content and moola and all these things,” Lentell said.

By Lentell’s account, Mxit’s value proposition weakened, making it easier for users to consider WhatsApp as a new alternative as it entered the market. Since then, WhatsApp’s network effects have entrenched the application as South Africa’s number one chat app.

Invariably, what most determines network effect is not who’s got the best product, it is who is first

The framework Lentell describes, a compelling value proposition combined with network effects, can be used to understand why Meta’s Threads is struggling to dethrone Elon Musk’s X as the incumbent microblogging application. Threads tried to simulate network effects by pushing for scale fast, using Instagram accounts to ease sign-ups. But without a compelling value proposition, users had no real reason to leave X.

The very same framework also explains why Facebook Messenger is dominant in North America. Facebook had huge network effects in those regions by the time WhatsApp arrived, and although it could be argued that WhatsApp provides a better chat experience, its value proposition is not superior enough to Messenger’s to be compelling to users.

“Invariably, what most determines network effect is not who’s got the best product, it is who is first. It is very difficult to take market share away from whoever captures it first, even if you have got a better product,” Lentell added.

Read: WhatsApp calling nightmare for SA’s mobile operators

ICQ, MSN, Jabber, Mig33 and others – all once prominent chat applications – benefited from the network effects derived from their once-innovative value propositions, only to suffer when a more compelling proposition came along and enjoyed network effects to steal market share from the incumbents. – © 2023 NewsCentral Media