Back in the day – sometime in 1993 – I was a 30-something media activist (with an ill-fitting suit). Despite my questionable dress sense, I was selected by anti-apartheid civil society groups and the ANC to be one of the drafters of the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) Bill – a law that would form part of a package of legislation negotiated and agreed to usher in South Africa’s democracy.

The IBA Act was passed in 1993. It became foundational to our broadcasting framework, and was a radical change from the apartheid state’s total, authoritarian control over broadcast regulation. The act established the IBA with a range of progressive statutory provisions, including community radio licences, quotas for on-air South African content, black empowerment licensing provisions, and a whole new system for regulating party election broadcasts and political advertising during election periods.

Fast-forward to the looming 2024 elections, and the interpretation of the law on political advertising has now been disputed for the first time. This is after the SABC rejected a political advert from the Democratic Alliance. The television ad itself was offensive to many South Africans. It depicted the burning of our national flag as part of a fear-mongering narrative to depict what would happen if the ANC was returned to power. The flag was then shown to be “made whole” if the ANC was voted out.

Outrage

The ad caused widespread outrage as the national flag had become a respected, unifying symbol of our three-decade-old democracy. President Cyril Ramaphosa and government ministers issued strong statements against the ad, with threats of court action. President Ramaphosa said the ad was “treasonous and despicable”. Minister of sport, arts & culture Zizi Kodwa said the ad was “a desecration of a national symbol” and that the government was considering its legal options. Despite all the sound and fury, my view was that, despite the advert being divisive, provocative, in poor taste and offensive, the ad itself constituted lawful political expression.

Shortly after statements by the president and minister Kodwa, on 9 May 2024 the SABC issued a statement saying it had rejected the ad for reasons that appeared questionable and (as required by law) had notified communications regulator Icasa, the IBA’s successor regulator.

In response to the rejection of the ad, the DA then submitted a formal complaint to Icasa’s complaints and compliance committee (CCC). On 17 May, oral argument was made by counsel for the SABC and the DA, battling each other over the meaning of the law. With the election just over 10 days away, this is clearly an urgent issue, and Icasa agreed to come back with a decision by early this coming week (starting 20 May).

Watch the DA ad that the SABC banned from its channels:

The main disputed clause in question was section 58(1) of the Electronic Communications Act – a provision which had been largely “copied and pasted” from the IBA Act of 1993¹:

A broadcasting service licensee is not required to broadcast a political advertisement, but if he or she elects to do so, he or she must afford all other political parties, should they so request, a like opportunity. (Author’s emphasis in italics.)

The intention of the legislature in 1993 was very simple: section 58(1) did not compel broadcasters to carry political ads, but if a broadcaster decided to carry them for one political party, then they had to give other political parties a “like opportunity”. The SABC’s argument for an inherent right to reject political ads would work if section 58(1) ended with a full stop after “advertisement” but it doesn’t.

As one of the original drafters of this provision 30 years ago, the question is: should the provision have been improved and made clearer over the years? The answer is obviously “yes”. In fact, I have written before that the entire broadcasting framework is outdated and mostly archaic. However, many industry legal experts agree that section 58(1) still does not give SABC an inherent right to refuse to broadcast a political ad, and certainly not for the reasons advanced by the public broadcaster (in the letter to Icasa.)

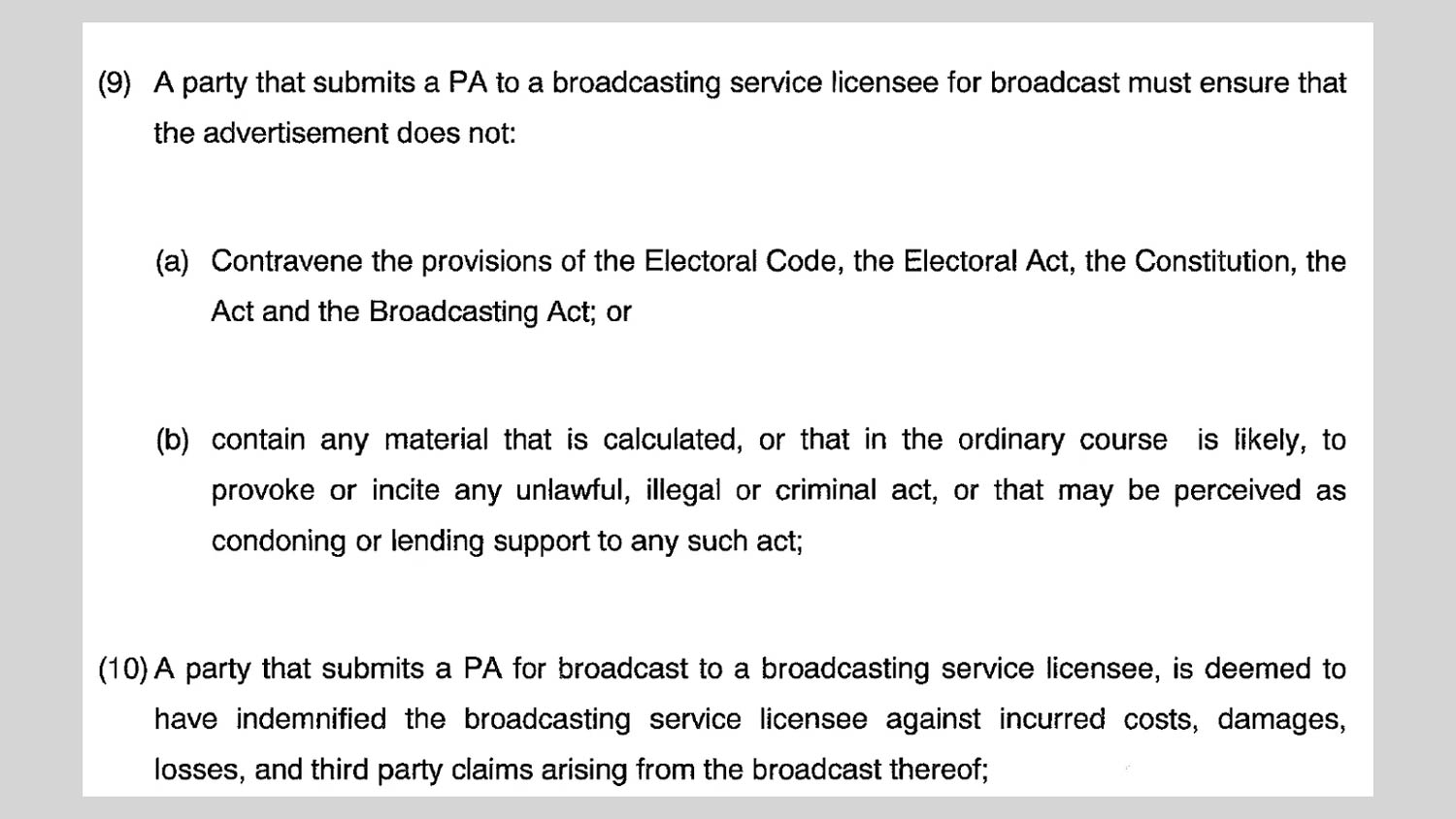

The regulations make it even clearer that as long as the content does not breach the law or incite “unlawful, illegal and criminal acts”, then there is no valid reason to reject it. In addition, broadcasters are indemnified from any legal liability for party political adverts broadcast on their platforms.

But during oral argument on 17 May, it became clear that the SABC was not claiming that the ad was unlawful or fell foul of the regulations. It claimed an inherent right to reject the ad because, among other reasons, the SABC was responsible for “nation building” and the DA’s “political advertisement goes against the spirit of nation building”.

The SABC made a number of other debatable legal arguments, the most striking being that Icasa does not have the remedial power to compel the SABC to broadcast the DA’s ad. Despite agreeing that Icasa had jurisdiction over the dispute, the SABC’s counsel argued that the broadcaster’s decision was an administrative act and only a court of law could order it to broadcast the ad. This position seems to be at odds with the legislation and regulations, which created a very specific framework for political ads during elections, including a dispute resolution process. Why set up this elections-specific framework under Icasa’s jurisdiction if only a court could order remedial action?

These questions will no doubt be answered soon. I look forward to the Icasa committee’s final decision and the Icasa council’s implementation of the ruling. I also hope that the matter is not ligitated in the courts and can be resolved before the election on 29 May.

- Michael Markovitz is head of the Gibs Media Leadership Think Tank

- This article was originally published on Markovitz’s Media Explorations blog on Substack and is republished here with his kind permission

Footnote

¹In 1993 political ads were only allowed on sound (radio) broadcasters. This was later broadened to include political ads on television. Apart from this, section 58(1) of the Electronic Communications Act, 2005 is exactly the same as the original language of section 60(1) of the IBA Act, 1993: “A sound broadcasting licensee shall not be required to broadcast a political advertisement, but if he or she elects to do so, he or she shall afford all other political parties, should they so request, a like opportunity.”